~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

From Famous Castles & Palaces of Italy, Illustrated in Colour from Paintings, by Edmund B. d’Auvergne, London: T. Werner Laurie, [undated, 1911]; pp. 219-256.

FAMOUS CASTLES AND PALACES OF ITALY

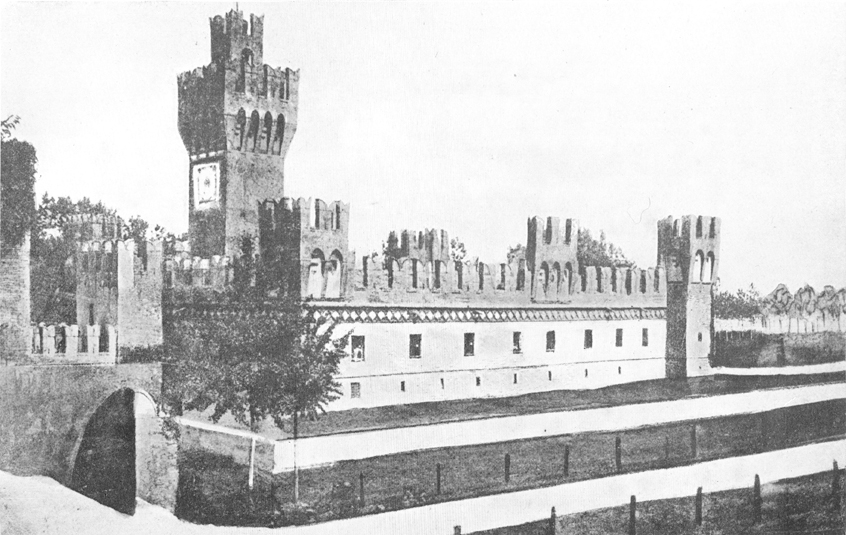

THE CASTLE OF FERRARA.

FROM A PAINTING BY C. E. DAWSON.

CHAPTER X

FERRARA AND ESTE

FERRARA is a city that should be dear to the devotee of monarchy and strong man rule. It is practically the creation of its princes of the antique brood of Este. By them it was dragged from obscurity, with their departure it relapsed into the deepest shadow of history. Its people played the part of chorus in the Æschylean tragedies of their sovereigns. The stage was that castle that occupies the centre of the city, which indeed you might suppose to have grown up around it.

It was not so; and the house of Este had long been settled in Ferrara before that pile was reared. We hear of them first in Tuscany in the tenth century, but this was not considered by the court chroniclers an antiquity respectable enough. The Estensi were, we are credibly informed, as old as the hills; to trace their ancestry to the Trojans was child’s play to the least expert genealogists; and they only stopped short there for fear that it might turn out that the princes were descended, like their subjects, from Adam. It was not however, till the eleventh century that the family did anything very remarkable. The Marquis Albertazzo then lived a hundred years without interruption, and found time to spread his sway for many leagues round the little town of Este, after which his 220 house came to be called. In the last years of the twelfth century they ranked among the most powerful citizens of Ferrara; and, as some say, their chief, Obizzo, carried off by force the heiress of the equally powerful house of Adelardi and married her to his own son. This bold step angered the Torelli, to whom the girl had been bequeathed by will; and the contention was continued by force of arms long after the lady had ceased to be a suitable match for any but a centenarian. The Emperor Otto IV., visiting Italy, effected a reconciliation between the rival chiefs; but they flew at each other’s throats as soon as his back was turned. The city wearied of this perpetual strife, and in 1208 solemnly named the Marquis Azzolino of Este hereditary lord of Ferrara. First of Italian cities was she to throw away her liberties. Nor did this base surrender bring her peace for many a long year. The infuriated Torelli returned to the charge and strove to oust their hated rivals from their place. In the wars that followed, the house of Este espoused the Guelf side, their foes were Ghibellines. Azzo Novello of Este lost for a time his lordship of the city, and meanwhile led the army of the crusade against the terrible Eccelino da Romano. He lost and regained his ancestral town; and at last, s some will have it, by treachery, he recovered Ferrara.

So long as he lived, thenceforward, he kept his foes at a distance. He took part in the reduction of the Emperor Frederick’s new city of Vittoria, from which he brought back as trophies two lions — of flesh and blood or of stone as you choose to believe. They gave, at all events, its name to the Porta de Leoni, through 221 which they were brought into the town, and to the tower afterwards built over it. And, having thus yoked lions to his triumphal car, the victorious marquis brought down bigger game by defeating and trapping Eccelino himself in 1259. The monster tore off the bandages from his wounds and died; or, by another account, was slain with a scythe by one whose brother he had murdered. Two years after, Azzo Novello died.

For three hundred years his posterity ruled Ferrara and Modena and Reggio, and many broad lands beside. They were an able, vigorous race, and maintained their vitality unabated almost to the last. This was, no doubt, due to their practise of electing the ablest member of the house, legitimate or illegitimate, as its head, instead of acting on the inevitably fatal and stupendously imbecile rule of selecting the eldest surviving male child of the last ruler, born in wedlock. Natural laws can hardly be expected to operate if brought within fanciful restrictions like this. Of course, the succession in Ferrara was often and often disputed, but such contests again resulted in the strongest, if not the best, man winning. Despite terrible vicissitudes, Ferrara flourished; despite the ferocity of their rulers, the citizens loved them. In 1312 the Marquis Francesco was murdered by papal partisans, and his fiefs escheated to Mother Church; but five years later the people rose, slaughtered the Pope’s troops, and enthusiastically reinstated the princes of Este. But peace was only secured by acknowledging the suzerainty of Rome.

In wars and pestilence the little state saw the unlucky 1300’s go by. She staggered like a frail 222 ship in a raging sea, but her helm was ever held by a stern-faced, resolute pilot. Women and war were the chief delights of the Estensi. The usual laws of Christian sex relations seemed to be almost unknown in Ferrara. Dante refers to the Marquis Obizzo’s intrigue with the fair Ghisola; Ariosto sings of his ancestress, “la bella Lippa” of Bologna, the mistress of another Obizzo. This lady’s son, Ugo, was a warm friend of Petrarch. That itinerant genius visited Ferrara as an old man — you can see the hills amongst which he died from the city on a clear day. Poets and troubadours and wits clustered at the court of the Este, which, I think, for all the alarms and excursions of the period, must have been a delightful place enough.

In those days the marquises dwelt in a palace facing the market square, which can now be recognised with difficulty as the town hall. Built at the close of the twelfth century, it was embellished by Giotto, restored, enlarged, gutted by fire, and finally remodelled in the year 1739 — a year not favourable to artistic development. At the present day the edifice contains but the scantiest traces of its former splendour. The place was intended for residence, not defence; and so long as a good understanding existed between the princes and people there was no need for a fortress. But the state in which the marquises lived had to be paid for; and in the year 1361 the docile citizens at last revolted. Their anger was not, of course, directed against their sovereign Niccolò II., surnamed il Zoppo, who, it was confidently supposed, could do no wrong, but against one of his officials, Tommaso de Tortona 223 by name. A furious mob invaded the unpopular collector’s house, burnt his papers, and drove him to take refuge in the palace. Niccolò found his own life threatened; the people, in their wrath, forgot the reverence due to their prince, and imperiously bade him surrender the fugitive. A marquis’s life is obviously more valuable than a tax-gather’s, and the demand was complied with. Tortona was thrust into the street, and was torn limb from limb. The citizens flaunted the bleeding fragments from one end of the town to the other, and next day fawned upon the marquis with protests of fealty and affection. Niccolò was not, probably, greatly concerned at the death of the luckless Tommaso, but he could not forget that the dog had once turned on him. He summoned troops from his other subject cities, and presently exacted a bitter vengeance upon his rebellious vassals. Never again, he vowed, should he or his descendants lie at their mercy. He would build a fortress, and straightway he invited Bartolino Plotti of Novara to design and to superintend the work.

The castle was begun in 1385 — twenty-five years, therefore, after the stronghold of Pavia had been built for the Visconti, probably by the same architect. The site selected, now in the very centre of Ferrara, lay then on its northern verge, so that the lord could obtain help from or escape at need into the country. I have seen this castle on a winter evening, when the rain had driven every wayfarer from the streets, and again in the sunshine of a spring morning, but its aspect never appeared to me, on the one hand, as forbidding as that of the town halls of Florence and Perugia, or, on the 224 other, as at all reminiscent of the willow-pattern plate to which Mr Hare compared it. The moat that washes its walls on all four sides is deep and green, and is productive of much placid contemplation if not of sport to numbers of patient anglers at all hours of the day. From a battered plinth, pierced with slits and marked off with a stone string-course, the brick walls rise to the stone balustrade that has replaced the former battlements. This is carried on the old machicoulis, and above it rises a storey, added in the sixteenth century, which has robbed the building of much of its sombre grandeur. Similar additions have been made to the rectangular corner towers, and to the lower towers that project more boldly from the middle of each side. From these middle towers drawbridges, supported by permanent stone piers, are swung across the moat on the north and west sides, defended halfway, as at Milan, by lesser square towers or battleponti with machicolated galleries. On the east side the middle tower seems to have been built out so as to include the battiponte, being carved over the ditch on an arch, almost to the counterscarp, and running into the north-east turret. This last is called the Torre dei Leoni, flanking as it does the old gate of that name, and bearing a bas-relief which commemorates the famous beasts of Vittoria. The southern gate, before the enlargement of Ferrara by Ercole I., alone admitted to the city. The moat, now fed by underground conduits, was formerly supplied by a canal from the southern branch of the Po.

The castle before Alfonso II. clapped the balustrades and upper rooms upon it must have looked a formidable 225 citadel, and such it remained, and that only for a hundred years after its foundation. The marquises, presently exalted into dukes, continued to dwell in the Corte Ducale, ready to flee at a moment’s notice into the stronghold across the covered gallery which connects the two buildings at the south-east angle. Indeed, the reign of Niccolò II.’s brother Alberto was, thanks to his alliance with Milan, fairly peaceful; though it may have been then that the castle received its baptism of blood by the execution, perhaps within its walls, of the marquis’s nephew, Obizzo, and his mother.

It is to Alberto’s son and successor, Niccolò III., that the castle owes its sinister celebrity. He was a great prince within the narrow field allotted to him, and by no means the worst of his contemporary sovereigns. Everyone that has written at all of Ferrara has told of his passion for travel and curiosity for strange sights. He visited the Holy Land and was hardly less devout a pilgrim to the shrines of the pagan gods which he chanced to visit on the way. He went even as far as Santiago in Spain, and, like Richard Cœur-de-Lion, on his way back was captured by a robber knight and released only at the eleventh hour by the Count of Savoy. The child of passion himself, both at home and abroad love was his chief delight. The old joke about the prince who was truly the father of his people found expression in the lines: “Di qua e di là del Po, Tutti figli di Niccolò” (On this and that bank of the Po, all are the children of Niccolò!). His first wife, too much engaged in looking after the children of her husband’s mistresses, bore him none of her own. But in 1416 she died, and the marquis 226 three years after married the ill-fated Parisina, daughter of Andrea Malatesta, Lord of Cesena. The fifteen-year-old bride lacked not any of the beauty of her house nor its traditional impetuosity in love. She was light-hearted and emotional, yet renowned for her housewifely prudence. A recent historian of the city1 shows the court life of Ferrara, beneath all its gilding, to have been as bereft of comfort and convenience as that of Milan. The young marchioness found it at times a hard task to clothe her husband’s numerous progeny decently. She added to this brood two daughters of her own, but these, she presently discovered, were less dear to her than Ugo, her lord’s first-born son by the lovely Stella dall’ Assassino. He was a handsome and promising young man, older than she, and destined by his father to succeed him. He seems to have constituted himself her squire and constant companion, without arousing the jealousy of her father, who of all men should have been most suspicious of such relations. Parisina’s life, while it lasted, was free and joyous; but happiness more than sorrow craves for love. Doubtless she could find no reason to resist her passion for her husband’s son. Niccolò supplied her almost daily with living proofs of his own infidelity, and could hardly be supposed to be much in love with her. Ugo, on the other hand, could not blame himself for following his father’s example, and for avenging the slight he had put on his own mother by marrying during her lifetime.

227At all events Parisian and Ugo loved each other, and may have known it when they journeyed to Rimini or Ravenna in the spring of 1424 on a visit to the lady’s kinsfolk. Among the scenes where Paolo and Francesca had loved and suffered, their passion may have burst into flame. They returned with their fearful joy to Ferrara. The world, it is said, loves a lover; it certainly watches his movements with the liveliest interest. The princely pair had perforce to take their more intimate attendants into their confidence. Aldobrandino Rangoni afterwards paid for his privity with his head. The marquis had a servant named Rubino, called, I know not why, Zoese. On this man’s daughter, Pellegrina, the marchioness had lavished kindness; but it was he who betrayed her. Passing one day by her door, he found one of her handmaids weeping with pain and rage. She had been beaten, according to the domestic customs of the time, for some fault, and now sobbed out the story of her mistress’s love. Rubino hurried to his master with the tale. An angry man was the Marquis Niccolò. He writhed beneath the indignity. The irony of it! — that the son should take the woman his father had put into his dead mother’s place! A man of the modern world might have found a grim humour in the situation. But those were the ages of faith, and no one had any sense of right and wrong. Niccolò knew only that he had been betrayed by his own wife and son, filched of one of his cherished possessions by his vassal. Spies were set. The pair were surprised, and hurried over the gallery into the castle built forty years before. We may follow the fainting marchioness down 228 into the base of the Torre dei Leoni. We can creep down through a narrow flight of stairs; she was thrust down through a trap-door into the arms of a gaoler waiting to receive her. The party stood in the narrow passage, beneath the level of the moat, while one of them unlocked a heavy iron door. Within this was another. A turn of the key and a long, narrow, tomb-like chamber was revealed. Light penetrated only by a single loop in the wall. The men held their lanterns aloft, while they pushed the half-dead girl forward into the dungeon. She stumbled within the second door; it clanged upon her; and a moment later the outer door closed too.

Her lover with less difficulty and perhaps more violence was hurried to his cell not far off — beneath the central eastern tower, as far as I could judge. Not one but three doors shut him in, and the touch of the walls must at once have set him shivering. The only ray of light came through a loophole in the castle wall, across the passage, and through a double grating in the wall of the cell. It mattered little, the youth must have told himself; it was not for long; and then doubtless he asked himself if it was possible after all for a father to slay his son.

The benevolent traveller (if he still exists) may, however, hope that these luckless lovers were as hardy and as easily pleased as that lively American, Mr W. D. Howells. He thought it impossible to deny that both the cells were singularly warm, dry and comfortable; and found it hard to realise the terror and agonies of the miserable ones who suffered there. For my part, I fancy that twenty-four hours’ seclusion 229 in either would make me welcome the executioner with something like cordiality.

The prisoners had not long to wait. Uguccione de’ Contrari and Alberto della Sala, the most trusted ministers of state, threw themselves down before the marquis and implored him not to stain his hands with the blood of his own son. Niccolò was deaf to their entreaties. He was asked to let the captives plead their cause before him. He refused to see either of them again. All that twenty-first day of May the counsellors came and went, and hovered around him, renewing their appeals for mercy. But the executioner had his positive orders. That night the three doors of Ugo’s cell were unbolted and the confessor entered to prepare him for instant death. Men in those days were better prepared for such a summons than they are now. Then he was led swiftly along the passage to a chamber beneath the Torre Marchesana — the present clock tower — and his head struck off. Then the gaolers went back for Parisina.

They said no word but hurried her along the dark passage. She thought she was to be thrown into an oubliette and asked again and again if they had yet reached it. Then they told her that she was being taken to the block — in five minutes more she would be dead. She asked how it fared with her lover. She was told that he was already dead. “Then,” she said, “I no more wish to live.” Death after such an announcement must indeed be a relief. When she came to the block she took off her necklace — for she had been hurried from the court into her dungeon in her bravest apparel — and bared her fair throat to the blow. Soon 230 after, a party of Franciscan friars were seen escorting a funeral bier to the little graveyard adjoining their church. But the people did not yet know what had happened.

In the adjoining palace the wretched marquis strode up and down, biting his lips, gnashing his teeth, and uttering strange cries. He was a prey to the most hideous emotions. They told him that his orders had been executed. He wailed piteously and screamed out the name of his headless son. And then, in a paroxysm of rage, he wrote out an order for the immediate execution of all the faithless women in Ferrara. His wife should not be the only one to suffer. The dreadful flame of wrath spread beyond the palace walls, and caught unsuspecting women, aghast and clamant. Laodamia de’ Romei was dragged to the block, because the wife of the marquis had been untrue to him.

It is a sad story enough; though as I heard the door of Parisina’s cell clang behind me, I consoled myself with the platitude that, if the lovers had lived a hundred years, they would still have been dead a long time. When we consider how bright and gallant were their short lives, and how their agony endured but a night and a day, I am not sure that they may not be said to have drawn a big prize in life’s lottery.

“And Ugo found another bride,” sings Byron, “and goodly sons grew by his side.” Notable among them was Ugo’s brother, Leonello, who had luckily been absent at Perugia during the tragedy. He now became the idol of his father, and the favourite of all his contemporaries. He was the pupil of the learned Guarino, and a humanist himself of no inconsiderable merit. 231 His learning was displayed with great effect at the council held at Ferrara in 1438 with a view to reconciling the Eastern and Western Churches. The Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople were there, and barons and soldiers sank into insignificance beside doctors and scholars. Leonello harangued the Pope in excellent Latin, and his father looked on in wonder and delight at this son who embodied the spirit of the new age. Perhaps with an ache he thought of the other son, who had in him more of the spirit of the age that was passing away. And Niccolò III. himself passed away in 1441.

Leonello made an excellent sovereign, and under him Ferrara became the Athens of Italy. His reign of nine years was untroubled by war. “He was a lover of justice,” writes one of his subjects, “of most honest life, a lover of piety, most devoted to the divine religion, a lover of the poor, liberal to the needy, a studious hearer of the holy scriptures, patient in adversity, moderate in prosperity. He ruled his people in peace with great wisdom.”

Borso, his brother (and Ugo’s), succeeded him, to the exclusion of his son and their legitimate brothers, Ercole and Sigismondo. And now began the golden age for Ferrara. The emperor Frederick III. came to the city and in the square before the cathedral created Borso Duke of Modena and Reggio — places of which the Estensi had so far been only the lords or counts. There were brave doings in all the cities in his states — streets strewn with green boughs, carpeted with rich stuffs, pageants, interludes, jousts and troops of maidens robed in white. In 1459 the duke’s old friend, Æneas 232 Sylvius, now Pope Pius II., passed through the city on his way to Mantua, to preach a new crusade against the Turks; and as a result of his visit, in 1471, Borso was made Duke of Ferrara before the altar of St Peter in Rome.

The virtues and the magnificence of the new duke are described almost rapturously by contemporary writers. Having loaded his people with taxes, he was able to be liberal to individuals and hospitable to his equals; he encouraged men of letters to frequent his court, though he was not himself learned, and he was kind and courteous to those with whom he had no quarrel. But in his golden reign the dungeons of the Castello Vecchio, as the castle now came to be called, seldom lacked occupants. In 1469 a conspiracy to place his brother Ercole on the ducal throne was hatched by the Pio family, lords of Carpi. The King of Naples, the Duke of Milan, and Piero de’ Medici are all accused of having abetted the design. Giovanni Lodovico Pio disclosed his project to Ercole at Modena, and the prince feigned acquiescence, only to reveal the whole plot to the duke during a hunting expedition. The conspirators were trapped in the garden of the castle of Modena while awaiting Ercole, and were taken by him to Ferrara, where they were soon joined by another brother from Carpi. They were imprisoned, it is said, in Ugo’s prison, and thence two of them were taken to their doom in the adjoining square on 12th August. Giovanni Marco Pio was put to death a month later in his prison. Meanwhile the five other brothers, Gian Marsilio, Gian Princivalle, Manfredo, Bernardino and Tommasso were arrested and confined 233 beneath the moat. They protested their innocence, but were denied a trial or even an audience of the duke. Their cousins, eager for their fiefs, loudly asserted their guilt. They suffered great hardship in these underground dens, full of slime and darkness, and succeeded on one occasion in escaping. They disguised themselves as friars, but three of these played the part so ill that they were detected and carried back to their prisons. Only in 1477, on their renouncing all claims to their fiefs, were they set free.

While Borso lay dying, on his return from Rome, at his country seat of Belfiore, the castle was seized and garrisoned by the Veleschi, the partisans of Niccolò, the son of Leonello. He asserted his claims to the succession against those of Ercole. There was fighting in the streets, quelled by the appearance of old Borso, who was brought into the castle on a litter. He sternly ordered Niccolò to retire to Mantua, Ercole to Modena. His nephew obeyed, his half-brother did not, but hovered on the outskirts of the capital. On 19th August 1471 the old duke died in the castle where his brother had been hurried out of life forty-six years before. Three days later he was followed to his tomb by a mighty procession headed by Ercole clad as duke.

He was, by the way, the first sovereign of Ferrara to have been born in wedlock since Obizzo III., who had reigned one hundred and twenty years before. He was, notwithstanding, one of the true Este brood, and if he lacked some of his forefathers’ courage he lacked none of their sensuality and capacity for 234 government. He was pious and trusted much to the protection of the Virgin — “and he trusted a little likewise in the assassin’s dagger and the poisoned cup, no less than in the axe of the headsman.”2

Two years after his accession, Ercole brought his bride to Ferrara, amidst scenes of unparalleled magnificence. She was Eleanora, daughter of King Ferdinand of Naples, and all men went mad over her beauty and her queenly bearing. Even poor Pio seemed to feel some ray of sunshine from her presence penetrate his prison bars, and hoped she would take him from his dungeon. She danced in the palace, her black hair flowing down her shoulders and a crown on her head, “the splendid queen” of Ariosto. On 18th May 1471 she gave birth to a daughter, the famous Isabella d’Este; a year after to another daughter; and thirteen months after that to the longed-for son.

The infant prince was only six weeks old, and his father away at Belriguardo, when the bells of Ferrara rang out a wild alarm. There were cries of “Vela! Vela!” in the piazza. The duchess knew not what this meant. Her attendants paled and told her. It was the war cry of the detested Niccolò, who had swooped down on the city with seven hundred men. Catching up her baby, Eleanora fled across the gallery into the castle, followed by her women with the two little girls. Happily her lord’s brothers were there. They raised the drawbridges, and from the battlements beheld the pretender seated on an imprisoned throne in the piazza. A crossbowman struck down a man by his side. Then Sigismondo d’Este sallied out of the 235 castle into the suburbs, collected a force, and rushed into the square. A brisk fight took place between the cathedral and the palace; Niccolò’s men gave way, and he was captured and brought a prisoner into the castle. Ercole, on hearing the news of the descent, had fled to Lugo, but next day, finding that he had been vicariously victorious, he returned to Ferrara. Finding his wife and children safe and sound he wept for gladness, and proceeding to the cathedral offered up thanks to heaven for his deliverance. Two days later he hanged five of his prisoners over the castle battlements, and eighteen others from the handy balcony of the Palazzo della Ragione. On the night of 4th September Niccolò was beheaded in the great quadrangle of the castle. The deed was done privately and decently, and next day the body was carried to the tomb with every sign of respect. The head had been sewn on to the trunk, and the corpse was most richly arrayed. The duchess, looking down from the balcony, wept bitterly. The rectors of the university, the magistrates, ambassadors, counsellors and clergy all followed the bier by order of the duke; and it was perhaps in a grim but sincere spirit of chivalry that he thus did honour to a kinsman and a lifelong antagonist. He was ready to spare one of his prisoners, Luca, Niccolò’s cook, if he would cry “Viva la Diamante!” (the Herculean war cry), but the fine old fellow shouted instead “Viva la Vela!” and was instantly beheaded. When, at the end of the year, a list was brought to the duke of those of the conspirators who still remained unpunished he threw it, without reading it, into the fire. “Let the memory perish,” he said, 236 “of all that they have thought, tried and done against me.”

Alarmed by this attempt on his life and throne, Ercole determined to make the castle his permanent abode. Pietro di Benvenuto designed the ducal apartments, which were ready for occupation in December 1477. Here the duke and his beautiful wife lived happily, united by a great love, till the approach of the Venetian army drove them for refuge into the Castello Nuovo, another citadel on the outskirts of the city, which has long since disappeared. While the duke lay there, seemingly a dying man, the city was ravaged with pestilence, threatened with famine and beleaguered closer and closer by the enemy. At the eleventh hour Ferrara was saved by the sudden interposition of the Pope. The legate came to the bedside of the afflicted sovereign, and promised him salvation from the Lord. The people wept for gladness, and the papal standard was hoisted over the castle. The duchess’s brother, the Duke of Calabria, having now been allowed to pass through the states of the church, marched with an army to the relief of Ferrara and forced the Venetians to retreat. But his victory was far from decisive, and the war dragged on for some time longer, to be terminated ingloriously for the little duchy by the cession of Rovigo to the merchant republic.

To console himself for the diminution of his territory, Ercole enlarged his capital by building the large quarter to the north of the Giovecca that bears, or did bear, his name. The walls round it were begun in 1490. The new spacious streets and squares procured for Ferrara the title of the first modern town in Europe. The 237 castle instead of being on the verge was now in the very centre of the city. Gardens were planted on each side of it, and Ercole lived there till his death in 1505.

Perhaps because the walls smelt of Este blood, it was not preferred as a place for court ceremonies, and rejoicings; and it was at the Corte Vecchia that the famous Lucrezia Borgia was entertained on her marriage to Ercole’s son and heir. The Pope’s daughter made a good wife to Alfonso I., as the new duke was styled, and steadfastly resisted the languishing glances of poets and courtiers. Her beautiful kinswoman, Madonna Angela, was not so discreet. She soon set aflame the hearts of two of the duke’s four brothers — the Cardinal Ippolito and Giulio, the son of Ercole by Isabella Arduino. “My lord,” said the lovely Borgia to the amorous churchman, “your brother’s eyes are worth your whole body.” The taunt was not forgotten. One day while hunting near Belriguardo, Don Giulio was surrounded by a band of masked varlets, who dragged him from his horse and pierced his fine eyes with the points of their swords. The cardinal, who had stood by disguised while this was being done, hurried off to the duke to tell him that their brother had been barbarously maltreated by some brigands. Alfonso, in violent wrath, declared he would find the villains if he had to search all Italy. Ippolito had taken care to get them out of the way, but he could not altogether divert suspicion from himself. Strangely enough Giulio recovered the sight of one eye, and the duke, who was devoted to his cardinal brother, insisted upon a reconciliation between them. It took place in form only. So ghastly an outrage 238 could hardly have been forgiven by mortal man. Giulio was presently offered a means of gratifying his just resentment. His elder brother, Ferrando, had long wished to supplant Alfonso on the ducal throne, and he now drew the injured prince into a conspiracy which was to mean death to both duke and cardinal. The carnival of 1506 was fixed for their assassination; but, though the destined victims mixed freely with the masked crowd, the courage of the would-be murderers failed them and they went unharmed. The existence of the plot was revealed to Alfonso. Ferrando asked mercy on his knees. “You shall be as blind as your bastard brother,” screamed the despot, and truck out Ferrando’s eye with the stick he held. Giulio had taken refuge with his sister at the court of Mantua. Alfonso persuaded his brother-in-law to give him up and had him brought back to Ferrara by a guard. He was thrown with his fraternal accomplice into the dungeon below the Torre dei Leoni. A few days later, they were led, half-blind, up into the quadrangle of the castle. Around on stages, and at all the windows, were seated the duke with his magistrates and the whole court. Two men, clad in scarlet, helped the princes on to a scaffold. Clearly their brother had come to witness their execution. The two men commended themselves to God. Then the duke rose and announced that he spared their lives. They were taken back to their prison, and thence to a more commodious place of confinement in the upper storey of the tower. There Ferrando lived for thirty-four years, and died in 1540. Nineteen years later, Giulio, an old man, blind of one eye, dressed in the costume of a bygone age, was 239 suffered to go free, and died a year after — the victim of a brother’s jealousy.

Their accomplices had met with a swifter and perhaps more merciful fate. One of them, a priest named Gianni, after being tortured, was hung out of the castle wall in an iron cage. At the end of two days he was found to have strangled himself with a handkerchief that someone had passed to him through the bars. Madonna Angela, the innocent cause of the tragedy, was promptly married to one of the ill-fated family of the Pios of Carpi.

The duke and the cardinal soon forgot their half-blind brothers in the tower. They had to fight hard for the very existence of the little state, which the Popes Julius II., Leo X. and Clement VIII. threatened to absorb in their ever-expanding dominions. Alfonso allied himself with French and Imperialists in turn, having only one policy, that of self-preservation. He fought on the winning side at Ravenna, he gained barren victories over the Venetians, he went in person to Rome to plead his cause with the Sovereign Pontiff and escaped his pastoral clutches only by the timely assistance of the Colonna. He found in Ippolito a staunch ally. The dashing churchman is better remembered as the patron of Ariosto, whom you might have met constantly in those days loitering about his eminence’s chambers or talking with one or other of the many artists and poets that still frequented the ducal court. Ippolito proved a difficult master, and the poet was glad to exchange his patronage for that of the duke himself. He was weary, he tells us, of court life; and, indeed, things were no longer very gay within the castle walls. Lucrezia 240 Borgia spent most of her time in the chapel; Bembo, her poet lover, had come to regard her as a habit — she should have dismissed him five years sooner; and the duke had to tax his subjects almost to starvation point to keep the ship of state afloat.

THE CASTLE OF ESTE.

His son and successor, Ercole II., was visited with an affliction that he, doubtless, considered the worst that had befallen his family. On an upper floor of the castle, near that garden terrace on the eastern tower where the prefect now entertains his guests, you are shown a little chapel panelled with coloured marbles. There is none of those pictorial and sculptured emblems which give so specious an air of warmth and humanity to Catholic worship. This was the oratory of Renata or Renée, daughter of Louis XII. of France, who was married to the second Ercole in 1528. She was a sad, serious little creature, whose coming almost at once subdued the joyous pagan spirits of her husband’s court. She was oppressed by a sense of her own lofty position as daughter of France, and let it be seen that she did not think much of Ferrara or its duke. This, of course, did not add to the domestic happiness of Ercole, but for a wife’s coldness a man could always in those days find consolation in the smiles of a mistress; what troubled him was his duchess’s singular habit of speculation in religious matters. In the happy days before the Council of Trent, you could disbelieve anything so long as you believed nothing in particular; but the duke hardly knew what to think when he found his wife entertaining Huguenot refugees from her own country. He at first received them with a rather embarrassed 241 courtesy. “Enjoy yourselves, gentlemen,” we can imagine him saying. “That is our great idea at this court.” It was not, however, the idea of the black-gowned, gloomy-browed Calvinists. Among them, little suspected by the good folk of Ferrara, was, it is said, Calvin himself, who passed under the name of Huppeville. At his instigation, we may suppose, cries came to be raised during Mass, denouncing it as idolatrous. This was more than a Christian prince could tolerate. Ercole bestirred himself, and “Huppeville” was thrown into the prisons underneath the Palazzo della Ragione. Thence he was enabled to escape through the intervention of the duchess. His captors little knew what a prey had been snatched from them. Marot the poet, another of these cheerful sectaries, made good his escape to Venice The rest of the accursed were found to be the duchess’s own servants, and were ordered to submit themselves to examination by an inquisitor.

Renée made a great outcry. Her shrill protests against this violation of her household reached the ears of Francis I., who rated Ercole soundly for his barbarous misbehaviour. Marot, from his perch on the lagoons, sang of the duchess’s sorrows and her husband’s cruelty. The duke, probably refusing to believe that anyone could be seriously attached to the new doctrines, managed to soothe his wife and suffered her all-but-avowed Protestant friends to continue under his roof. Indeed, the pope himself, on a visit to the ducal court in 1543, smiled on the misguided princess, and no doubt told her husband that she would grow out of her foolishness. But she did not. Worst of 242 all, her views seemed to be gaining ground in Ferrara, and threatened to put an end to the reign of cakes and ale that had been ushered in by the Renaissance. The duke lost all patience when Renée refused to frequent the sacraments of the church. He banished her to a villa at Consandolo, where she promptly surrounded herself with a chosen band of Calvinists from France, Germany and Switzerland. She spitefully denounced the brilliant Climpia Morata as a Lutheran, and compelled her to leave the ducal court, which her youth and talent had adorned. The persecuting energy she had herself set in motion was soon directed against one of her own coreligionists, a young man named Fannio, whom the duke was badgered into hanging for heresy. He was the second man to suffer death in Italy for his religious opinions within several months.

With his wife, Ercole might have dealt sharply if it had not been for fear of offending France. His son, Alfonso, had been imbued by his mother with immense fervour for that country, and in 1552 he rode away from Ferrara and entered the French service. The time had now come for the long-suffering duke to put his foot down firmly on this scandal. He wrote to Henry II. plainly stating his grievances. His wife, he said, obstinately refused to abandon her errors or to permit her young daughters to perform their religious duties. The house of Este was being pointed to as a nest of heresy, and it would be difficult to marry the princesses to Christian princes. Ercole was determined to set his house in order.

He met with no opposition from the French king, 248 who expressed his willingness to take over certain of his kinswoman’s lands should it be thought necessary to confiscate her property. The Pope of Geneva, hearing what was brewing, sent one of his saints to comfort her. The duke removed his daughters from their mother’s house. Renée stood fast and resisted the persuasions and arguments of a Jesuit theologian sent her by King Henry. She was, therefore, put on her trial for heresy before the bishop and inquisitor of Ferrara. Found guilty, she was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment and her goods were declared forfeit. She heard her doom with the manner of a martyr and declared her unshakable constancy in her faith.

It did not last very long. After a few days’ imprisonment, attended only by two women, in the castle, she recanted her opinions and was at once released — to the unspeakable consolation of the court and the profound disgust of Calvin and his synod. The duchess did not find in the doctrine of predestination the same sustaining force as afterwards did the coarsely nurtured Covenanters of Scotland. Her conversion was, of course, only simulated. Though outwardly conforming to the Catholic Church, she dissociated herself from court life and lived in retirement during the rest of her husband’s lifetime. In 1560 she returned to her own country, where her declining years were troubled by her zeal for the Huguenots, and her affection for her eldest daughter, the Duchesse de Guise.

Her son, Alfonso II., who had succeeded his father the year before her departure, was by no means sorry to see her go. Ferrara under his rule knew an Indian summer. His court was more like a king’s, said one, 244 than a duke’s. Men of letters fattened at the expense of the state, and the people paid for gorgeous pastorals and pageants which they were not permitted to witness. All the pleasaunces round the city were linked up by a beautiful avenue over which the public roads were carried on bridges. The mistress of the revels was Alfonso’s sister, Lucrezia, who found Ferrara a congenial retreat from the unkindness of her husband, the Duke of Urbino. Culture and jollity and love in those days went hand in hand, instead of as in these melancholy times pursuing different paths. The courtiers of Ferrara divided their time between love affairs, revelling, and discoursing with wits and sages. Alfonso and his sister aimed at making a collection of great men, even as Ercole I. had been at pains to acquire saints for his human menagerie. They netted a noble singing bird in Torquato Tasso, who, however, gave them more trouble than all the rest of his brother poets taken together. He has been associated in story and tradition very much with the duke’s younger sister, Leonora, who had in reality much less to do with him than Lucrezia. In the Salla dell’ Aurora the guide will tell you that Alfonso surprised him in the act of kissing Leonora. The story is a myth. The princesses were much older than the poet, and he is far more likely to have reserved his kisses for the maids-of-honour. He became wayward and petulant, and began to stick knives into the servants. He was put under restraint and kindly treated, escaped from the castle, and one day burst in upon the duchess, breathing flames and ruin. Then began his captivity in the Hospital of Sant’ Anna, which was alleviated by visits from the 245 ladies of the court, and which has been absurdly misrepresented as a harsh and tyrannical imprisonment.

Had Tasso been among the lovers of the duke’s sister he might have fared worse. Alfonso II. was a tolerant prince, but he was jealous of what he would have called the honour of his house. There is an ugly story that he poisoned his first wife, Lucrezia de’ Medici, on a suspicion of her infidelity. When common fame coupled the names of the Duchess of Urbino and the Marquis Ercole Contrari, the duke looked grim. He invited the marquis to the castle and led him, in friendly discourse, into one of his private chambers. Here there were three other gentlemen, one of whom Contrari perhaps could not remember to have seen at court. As he talked with his sovereign, a hood was thrown over his head from behind and his arms pinioned to his side. Then the strange man deftly threw a noose round his neck and drew it tight. The marquis died without uttering a cry. Then his body was borne back by night to his palace, and everyone said he had died of apoplexy.

Lucrezia suspected the truth, and never forgave her brother. She paid her court to the papal power which, it was now evident, must soon overwhelm the duchy. Ferrara had always been held as a fief of the Church, and Alfonso’s three marriages had left him childless. His only brother was a cardinal, whom Rome would not dispense from his vows. His cousin, Cesare, whose father was a natural son of Alfonso I., the Pope refused to recognise as heir to the duchy. At the court of Ferrara men bade each other “eat, drink, and be merry, for to-morrow we die.” The duke almost 246 hid himself from public gaze. How strange must have been the life in a state and under a dynasty alike under sentence of death. Whatever good the duke sowed, he knew another and an alien power must reap. No ruler in those days had any conception of his duty to mankind; he had heard of duty to his state, and his state was about to perish. There was nothing to be done, nothing to live for, except amusement. And he amused himself well. The eyes of his courtiers turned towards Rome. They must be Pope’s men now.

In 1597 all was over. The duke died, and Cesare drove out of Ferrara to become Duke of Modena and Reggio, which were held of the empire, not of the Church. Surely no state has ever been so quietly extinguished. The people watched the last of the Este go, glad perhaps that they would no longer be burdened with the upkeep of a magnificent court. With the last of her dukes the glory of Ferrara departed; her name faded out of history. The next day Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini rode in and took possession of the duchy as a part of the papal dominions.

You may see the arms of this prelate and those of all the legates, his successors, down to the year 1849, in the long hall admitting to the prefect’s apartments. The series ends where a black space is painted over the inscription, “Here were the arms of Count Filippo Folicaldi, pontifical delegate from June 1849 to June 1856.” This is a way, borrowed from the Venetians, of perpetuating the memory of an oppressive governor. Next come the arms of the Sardinian commissioners and Italian prefects, down to the present holder of the office. To this hall you ascend by the great ducal 247 staircase, up which the duke once rode his horse, and the lower part of which has, as a tablet records, been altered and repaired by the legates. Something of the old splendour of the Este days still clings to the ducal apartments. The skill of the brothers Dossi has adorned the ceilings of the Sala del Consiglio and the adjoining room with representations of the games of antiquity, in testimony of the athletic tastes of Alfonso the Last. Overhead you see chariots racing, athletes throwing the trigon, swinging from ropes; the other eight frescoes depicting sports described by ancient writers. From these two rooms you pass into the Sala dell’ Aurora, the Torre de’ Leoni, associated by tradition with Tasso and Leonora d’Este. The magnificent decorations include the beautiful Four Phases of the Day, the work of Dosso Dossi, who died at Ferrara in 1542. Titian worked for the duke between 1516 and 1523, and received a lodging in the castle and a weekly ration of “salad, salt meat, oil, chestnuts, tallow candles, oranges, cheese, and five measures of wine.” He completed Bellini’s “Bacchanal” and executed the famous “Bacchus and Ariadne,” now in our National Gallery, and two “Bacchanals,” now at Madrid. All these works were sent off to Rome by Cardinal Aldobrandini on taking possession of the castle; they stood originally in the three cabinets close to the Sala dell’ Aurora, which now contain the Vendeminia of Dosso and two other Bacchanalian pictures attributed to Girolamo Carpi.

These few apartments are all that remain of the antique state of the princely Estensi. Their portraits have long since gone from the quadrangle where 248 Ferrando and Giulio were brought out, as they thought, to die. They held on for centuries longer to Modena, cleaving fast to old standards and ideals of government and forgetting that these had long become obsolete. The last dukes of Modena might have far surpassed sixteenth-century conceptions of statesmanship; but the people had grown up in the meantime and the middle of the nineteenth century saw their final expulsion from the land to which their ancestors had come a thousand years before.

Even at ESTE you will find few reminders of the race which took its name from the town. You walk down the long white street into the vast empty piazza, and see, climbing the hillside behind the houses, the walls and towers of a once-mighty stronghold. But this was the castle begun, as abundant records testify, on 28th July 1338, by Ubertino da Carrara soon after he had been invested with the lordship of Padua. If anything remains of the old home of the Estensi doubtless it must be looked for at the north-west angle of the enclosure, where on the highest ground stands the ruined master tower, or keep, shut in towards the interior by the fragments of what seem once to have been residential buildings. The original limit of the castle eastwards was the wall bordering the little stream of the Sirone. The wall of Ubertino covers a very wide area, roughly rectangular in plan, except where the steepness of the hill near the keep occasions an irregularity in the enceinte. The wall is crenellated with square battlements and flanked with twelve towers, which with two exceptions are open at the gorge, and are not set at right angles to the curtain. At the north-east 249 corner is a big machicolated tower of the fifteenth century, flanking a gateway. There was another entrance close to the keep which has been walled up. Modern buildings — a school, a museum and a carriage factory — have been built within the walls and the grand old pile is in a sadly neglected condition. I could glean no particulars of its history, and suppose that it was suffered to fall into decay on the annexation of the territory by the republic of St Mark. The process of disintegration is not likely to be hastened by any violent vicissitudes, for Este is the quietest place I have ever visited. It is quite unknown to foreigners, and I was tempted to believe that Petruchio, or one of his contemporaries, must have been the last guest, before me, to put up at its only inn. In such a place I was not surprised to find a botanical garden, but should have been much astonished to find anyone besides myself and the gardener in it. Este is, in fact, very much off the beaten track, and there I advise all travellers to leave it.

THE CASTLE OF VIGNOLA.

FROM A PAINTING BY C. E. DAWSON.

The ancestral houses of the great families that clustered round the Este’s ducal throne are better worth visiting. The noble Castle of VIGNOLA, on the Panaro, is easily accessible by rail from Modena or by steam-tram from Bologna. Its history has not been without incident. There was a castle here in the days of the Countess Matilda.3 It soon became a bone of contention between the people of Bologna and the bishops of Modena, and was frequently besieged and taken. The castle of those days was finally burnt by King Enzo, one of Frederick II.’s ill-starred sons. It 250 was re-erected, as castles always are, and passed into the hands of the marquises of Ferrara. During his nonage, Niccolò III. bestowed the whole fief in a caprice of generosity upon one of his boon companions, Uguccione dei Contrari, then a lad of twenty-one. The deed was dated 12th January 1401. Though the fortunate youth could hardly have merited the gift at the time, he earned it over and over again by his subsequent services to the donor. He remained Niccolò’s most trusted counsellor and dearest friend. His life was held in high estimation by his prince: one Gidini suffered death at Ferrara in 1404 for an attempt to assassinate him. For some years Uguccione seems to have left the service of the marquis, and we find him fighting under the banner of Jacopo da Carrara and deeply concerned in the affairs of Bologna. When the citizens threw off the yoke of the Pope, he persuaded them to elect him captain of the people; but his past relations with the Sovereign Pontiff excited their suspicions and he soon found it prudent to seek the shelter of the ducal throne. He it was who vainly endeavoured to divert his master’s wrath from the hapless Parisina and Ugo. He did not lose the marquis’s favour by so doing but remained with him till his death. On the accession of Leonello he retired to Vignola, where he had rebuilt the castle, and died full of years and honours in 1448.

His sons, Ambrogio and Niccolò, were jointly invested with the fief, which for a time was wrested from their family by Julius II. during his war with Ferrara. The attempt of the lord of Vignola to extend his authority over the village of Trecenta was 251 also unsuccessful and cost him several thousands of ducats in litigation. The castle was recovered by Alfonso, the great-grandson of Uguccione; and was escheated to the duchy on the private execution of Ercole Contrari in the Castle of Ferrara in 1575.

Vignola was put up for sale, and bought by Jacopo Boncompagni, Duke of Sora, for seventy-five thousand Roman scudi. This powerful noble had lands and castles in every part of Italy, and does not appear to have spent much time at Vignola. We hear no more of the famous stud of horses for which the domain was famous; and the chief use of the castle to its new owners was to supply the title of marquis to the heir of the house. The little town also gave its name to the illustrious architect, Jacopo Barozzi, who was born here in 1507 and was often employed by the last Contrari.

The castle is a very perfect example of a north Italian castle of the fifteenth century. It stands close to the bridge over the Panaro, and its walls on this side continued the wall which encircled the town. It is, as usual, quadrangular, with an inner court and rectangular towers at each angle. The machicolations of the towers and curtains are of very bold projection; on the side of the stream the corbels that support them spring out of the wall at about half its height. The principal entrance is on the town side, where there are an outer and inner gate-tower with a drawbridge swung between. On the river-side a gallery or covered way connects the castle with another heavily machicolated tower that once flanked the town gate admitting to the bridge. The inner court contains a well. The castle is in great part occupied by municipal 252 offices, but has undergone little structural alteration or restoration. The immediate surroundings are not very beautiful, but the view from the towers embraces Bologna, Modena and the Apennines, the pass over which the castle was intended to guard.

THE CASTLE OF SAN MARTINO IN SOVERZANO.

Nothing, on the other hand, can be less picturesque than the situation of the Castle of the Manzoli or SAN MARTINO IN SOVERZANO, the former home of the Ariosti. It lies in perfectly level country, about a mile from the miserable town of Minerbio, between Ferrara and Bologna. It will, I think, be admitted that the district of the Romagna is physically one of the most uninviting regions even in Italy, where plains become less interesting and tamer than anywhere else. The country would no doubt have delighted Mr. Arthur Young, being cultivated like one vast market garden. The tired eye finds relief only in the distant vision of the Apennines. The situation of San Martino offers no advantages from a military standpoint, but there was a castle here in the thirteenth century belonging to the Caccianemichi. From them it was acquired by the marquises of Ferrara. In the middle of the fourteenth century it was bestowed by Obizzo II. on Francesco Ariosto, the brother of his mistress Lippa. A few years later the republic of Bologna seized the castle on the pretext of defending it against foreign foes; but when, in 1390, a war with Milan was, in fact, imminent, it was hurriedly restored to Francesco. The poet who has made the name of Ariosto illustrious was fourth in descent from Francesco’s cousin, Niccolò. The castle passed to Bonifazio, one of the captains of Niccolò III. Perhaps because he 253 lacked money, perhaps because he had no sons, he sold San Martino on 1st September 1407 to Chiara degli Arrighi, the wife of Bartolommeo Manzoli, by whose name it is often called.

The ditch and the foundations of the existing structure are said to be the works of the first Ariosti, but the rest of it is modern and the result of a skilful restoration. The pile, which I was enabled to visit by the kindness of the present owner, Count Cavazza, presents a noble and beautiful appearance. It is, as usual, oblong in plan, and built of dark red brick. Facing the highroad the corner towers rise from the plinth; at the opposite angles they spring as heavy machicolated turrets from an ornamental cornice of about two-thirds of the height of the curtain wall. In the middle of each face is another such bartizan, as Scott would have termed it. The machicolation is confined to the towers and turrets. The spaces between the corbels are painted with coats-of-arms. The battlements are of the beautiful forked type and are pierced with loops. The approach on the south side is very fine. You cross a branch of the moat by a double bridge that can be received in the long open grooves of a fine embattled tower, and then find an embattled parapet defending the counterscarp or outer edge of the ditch round the castle. The drawbridge is permanent for the greater part of its length and defended on each side by a high crenellated parapet. At each end of it is an imposing tower bearing the escutcheons of the Manzoli. A little to the right of the inner gate rises the master-tower or maschio, carrying a superb machicolation and a smaller turret on the 254 platform. The interior of the castle is occupied by a charming cortile and loggia, from which the private apartments open on each side. Count Cavazza is as much to be congratulated on the magnificence of his residence as thanked for the courtesy he extends to visitors.

Notes

1 Ella Noyes, “The Story of Ferrara.” Cf. p. 193 of the present volume.

2 Gardner, “Dukes and Poets of Ferrara.”

3 Muratori, “Rerum Italicarum,” tom. 6, col. 92.

Next:

THE STRONGHOLDS OF THE

MALATESTAS

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~