From The Luck of the Bean-Rows, a Fairy-tale for Lucky Children, illustrated by Claud Lovat Fraser, London: Daniel O’Connor, [1921]; pp. 41-61.

It would be doing scant justice to

the speed of the magic carriage to

say that it shot through space at

the rate of a rifle bullet. Woods,

towns, mountains, seas swept by

quicker than magic lantern pictures.

Far away horizons had scarcely

risen in outline from the deep-down

distance before they had plunged

under the flying carriage. The

Luck would have striven in vain

to see them; when he turned to

look back — flick! they had gone.

At last, when he had several times

outraced the sun, swept round the

globe, caught it up and again

outstripped it, with rapid changes

from day to night and from night

to day, it suddenly struck the Luck

of the Bean-rows that he had

passed the great town he was

going to and the market for his

beans.

‘The springs of this carriage are

a trifle lively,’ he thought to

himself (he was nimble-witted,

remember); ‘it started off on its

giddy race before Pea-Blossom

could tell me whither I was bound.

I don’t see why this journey

should not last for ages and ages,

for that lovely princess, who is

young enough to be something of

a madcap, told me how to start

the carriage, but had no time to

42

say how I was to stop it.’

The Luck of the Bean-rows tried

all the cries he had heard from

carters, wagoners, and muleteers

to bring it to a standstill, but it

was all to no purpose. Every

shout seemed but to quicken its

wild career.

It sped from the tropics to the

poles and back from the poles to

the tropics, across all the parallels

and meridians, quite unconcerned

by the unhealthy changes of

temperature. It was enough to

broil them or to turn them to ice

before long, if the Luck had not

been gifted, as we have frequently

remarked, with admirable

intelligence.

‘Ay,’ he said to himself,

‘considering that Pea-Blossom

sent her carriage flying through

the world with “Off, chick pea!”

it is just possible we can stop it by

saying the exact opposite.’

It was a logical idea.

‘Stop, chick pea!’ he cried,

snapping his finger and thumb as

Pea-Blossom had done.

Could a whole learned society

have come to a more sensible

conclusion? The fairy carriage

came to a standstill so suddenly,

you could not have stopped it

quicker if you had nailed it down.

43

It did not even shake.

The Luck of the Bean-rows

alighted, picked up the carriage,

and let it slip into a leather wallet

which he carried at his belt for

bean samples, but not before he

had taken out the hold-all.

The spot where the flying carriage

was pulled up in this fashion

has not been described by travellers.

Bruce says it was at the sources

of the Nile. M. Douville places it

on the Congo, and M. Saillé at

Timbuctoo. It was a boundless

plain, so parched, so stony, so

wild that there was never a bush

to lie under, not a desert moss to

lay one’s head upon and sleep, not

a leaf to appease hunger or thirst.

But Luck of the Bean-rows was

not in the least anxious. He prized

open the hold-all with his finger-

nail, and untied one of the three

little caskets which Pea-Blossom

had described to him. He opened

it as he had opened the magic

carriage, and planted its contents

in the sand at the points of his hoe.

‘Come of this what must come!’

he said, ‘but I do badly want a

tent to shelter me to-night, were

it only a cluster of peas in flower;

a little supper to keep me going,

were it but a bowl of pea-soup

sweetened, and a bed to lie upon,

44

if only one feather of a humming-

bird — and all the more as I cannot

get back home to-day, I am so

worn out with hunger and aching

fatigue.’

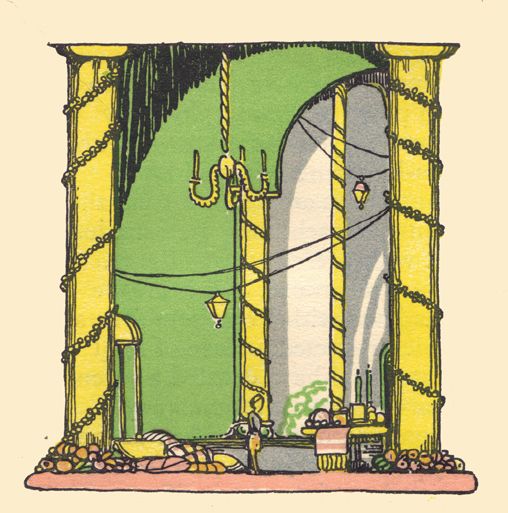

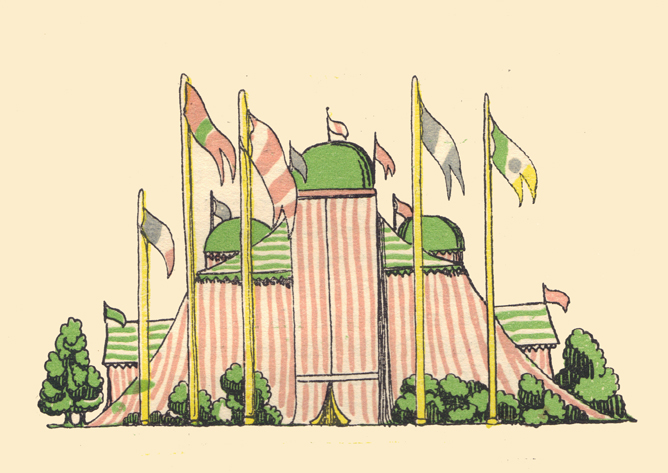

The words had scarcely left his

lips when he saw rising out of the

sand a splendid pavilion in the

shape of a pergola of sweet-peas.

It grew up, it spread; from point

to point it was supported upon

ten props of gold; it dropped

down leafy curtains strewn with

pea-blossom; it curved into

numberless arches, and from the

centre of each hung a crystal lustre

set with perfumed wax lights.

The background of this arcade

was lined with Venetian mirrors,

which reflected a blaze of light

that would have dazzled a seven-

year-old eagle a league away.

From overhead a pea leaf dropped

by chance at the Luck’s feet. It

spread out into a magnificent

carpet variegated with all the

colours of the rainbow and many

more. Around its border stood

little round tables loaded with

pastry and sweetmeats; and iced

fruits in gilded porcelain cups

encircled a brimming bowl of

sweet-pea soup, sprinkled over

with currants black as jet, green

pistachio nuts, coriander comfits

and slices of pineapple. Amid all

this gorgeous show the Luck quickly

discovered his bed, and that was

the humming-bird’s feather which

he had wished for. It sparkled in

a corner like a jewel dropped from

the crown of the Grand Mogul,

although it was so tiny that a grain

of millet might have concealed it.

47

At first he thought this pigmy bed

was not quite in keeping with the

rich furnishing of the pavilion,

But the longer he looked at it the

larger it grew, till humming-birds’

feathers were soon lying knee-deep

on the floor — a dream-couch of

topazes so soft, sapphires so

yielding, opals so elastic, that a

butterfly would have sunk deep

if he had lighted on them.

‘That will do, that will do,’

cried the Luck of the Bean-rows;

‘I shall sleep too soundly as it is.’

I need not say that our traveller

did justice to the feast that was

spread for him, and lost no time

in preparing for bed. Thoughts of

love ran through his mind, but at

twelve years of age love does not

keep one awake; and Pea-Blossom,

whom he had seen but once,

had left him with no

more than the impression of a

delightful dream, the enchantment

of which could only return in

sleep. Another good reason for

going to sleep if you have

remembrances like mine.

The Luck of the Bean-rows,

however, was too cautious to yield

to these idle fancies until he had

made sure that all was safe outside

the pavilion, the very splendour of

which was likely to attract all the

48

thieves and vagabonds for miles

round. You will find them in every

country.

So, with his weeding-hook in his

hand as usual, he passed out of

the magic circle, to make the

round of his tent and see that all

was quiet.

No sooner had he reached the

limit of the grounds — a narrow

ravine washed out by running

water that a kid might have cleared

at a bound — than he was brought

to a standstill by such a shiver as

a brave man feels, for the most

valiant has his moments of fright

which he can master only by his

resolute will. And, faith, there was

enough to make one hesitate in

what he saw.

It was a battle-front where in the

darkness of a starless night glistened

two hundred fixed and burning

eyes; and along the ranks, from

right to let, from left to right,

there ran incessantly two keen

slanting eyes which bespoke an

extremely alert commander.

Luck of the Bean-rows knew

nothing of Lavater or Gall or

Spurzheim, he had never heard

of phrenology, but within him he

felt the natural instinct which

teaches every living creature to

sense an enemy from afar. At a

glance he recognized in the leader

of this horde of wolves the

wheedling coward who had tricked

him, with his talk of enlightenment

and self-control, out of his last

measure of beans.

‘Master Wolf has lost no time in

setting his lambs on my track,’

said Luck of the Bean-rows; ‘but

by what magic have they overtaken

me, every one of them, if these

ruffians too have not travelled by

chick pea? It is possible,’ he

added with a sigh, ‘that the

secrets of science are not unknown

to scoundrels, and I dare not be

sworn, when I think of it, that it

is not they who have invented

them so as to persuade simple

souls the more easily to take part

50

in their hateful schemes.’

Though the Luck was cautious in

doing, he was quick in planning.

He drew the hold-all hastily from

his wallet, untied the second

pea-casket, opened it as he had

done the first, and planted the

contents in the sand at the point of

his weeding-hook.

‘Come of this what must come!’

said he; ‘but to-night I do badly

want a strong wall, were it no

thicker than a cabin wall, and a

close hedge, if only as strong as my

wattle fence, to save me from my

good friends the wolves.’

In a twinkle walls arose, not cabin

walls, but walls of a palace;

hedges sprung up before the

porches, not wattle fences, but a

high, lordly railing of blue steel

with gilded shafts and spear-heads

that never a wolf, badger, or fox

could have tried to clear without

bruising himself or pricking his

pointed muzzle. With the art of

warfare at the stage it had then

reached among the wolves there

was nothing to be done. After

testing several points the invaders

retired in confusion. Thankful for

this relief, the Luck returned to

his pavilion. But now he passed

on over marble pavements, along

pillared walks lit up as if for a

wedding, up staircases which

seemed to ascend for ever, and

through galleries that were endless.

He was overjoyed to come upon

his pavilion of pea-blossom in the

midst of a vast garden, green and

blooming, which he had never seen

before, and to find his bed of

humming-birds’ feathers, where, I

take it, he slept happier than a

king — and I never exaggerate.

Next day the first thing he did

was to explore the gorgeous

dwelling which had sprung out

of a little pea. The beauty of the

most trifling things in it filled him

with astonishment; for the

furnishing of it was admirably in

keeping with its outward

appearance.

He examined, one after another,

his gallery of pictures, his cabinet

of antiques, his collections of

medals, insects, shells, his library,

each of them a wonder and a

delight quite new to him.

He was especially pleased at the

admirable judgment with which

the books had been chosen. The

finest works in literature, the most

useful in science had been gathered

together for the entertainment and

instruction of a long life — among

them the Adventures of the

ingenious Don Quixote; fairy

tales of every kind, with beautiful

engravings; a collection of curious

an amusing travels and voyages

(those of Gulliver and Robinson

Crusoe so far the most authentic);

capital almanacks, full of diverting

anecdotes and infallible information

as to the phases of the moon and

the best times for sowing and

planting; numberless treatises,

very simply and clearly written,

on agriculture, gardening, angling,

netting game, and the art of

taming nightingales — in short, all

one can wish for when one has

learned to value books and the

spirit of their authors. For there

have been no other scholars, no

other philosophers, no other poets,

and for this unquestionable reason,

54

that all learning, all philosophy, all

poetry are to be found in their

pages, and to be found only there.

I can answer for that.

While he was thus taking account

of his wealth, the Luck of the

Bean-rows was struck by the

reflection of himself in one of the

mirrors with which all the

apartments were adorned. If the

glass was not fooling him, he must

have grown — oh, wonder of

wonders! — more than three feet

since yesterday. And the brown

moustache which darkened his

upper lip plainly showed that he

was passing from sturdy boyhood

to youthful manliness.

He was puzzling over this

extraordinary change when, to his

great regret, a costly time-piece,

between two pier-glasses, enabled

him to solve the riddle. One of

the hands pointed to the date of

the year, and the Luck saw,

without a shadow of doubt, that

he had grown six years older.

‘Six years!’ he exclaimed.

‘Unfortunate creature that I am!

My poor parents have died of old

age, and perhaps in want. Oh,

pity me, perhaps they died of

grief, fretting over the loss of me.

What must they have thought in

their last hours of my deserting

them or of the misfortune that

had befallen me!

‘Now I understand, hateful

carriage, how you came to travel

so fast; days and days were

swallowed up in your minutes. Off,

56

then; off, chick pea!’ he

continued as he took the magic

coach from the wallet and flung it

out of the window; ‘out of my

sight, and fly so far that no eye

may ever look on you again!’

And to tell the truth, so far as I

know, no one has ever since cast

eyes on a chick pea In the shape

of a post-chaise that went fifty

leagues an hour.

Luck of the Bean-rows descended

the marble steps more sorrowfully

than ever he went down the ladder

of his bean-loft. He turned his

back on the palace without even

seeing it; he traversed those

desert plains with never a thought

of the wolves that might have

encamped there to besiege him.

He tramped on in a dream,

striking his forehead with his hand

and at times weeping.

‘What is there to wish for now

that my parents are dead?’ he

asked himself as he listlessly

turned the little hold-all in his

fingers, ‘now that Pea-Blossom

has been married six years? —

for it was on the day I saw her

that she came of age, and then the

princesses of her house are married.

Besides, she had already made her

choice. What does the whole world

matter — my world, which was made

57

up of no more than a cabin, a

bean-field — which you, little green

pea,’ and he untied the last of the

caskets from its case, ‘will never

bring back to me! The sweet days

of my boyhood return no more!

‘Go, little green pea, go whither

the will of God may carry you,

and bring forth what you are

destined to bring, to the glory of

your mistress. All is over and

done with — my old parents, the

cabin, the bean-field and Pea-

Blossom. Go, little green pea, far

and far away.’

He flung it from him with such

force that it might have overtaken

the magic carriage had it been of

that mind; then he sank down on

the sand, hopeless and full of

sorrow.

When Luck of the Bean-rows

raised himself up again the entire

appearance of the plain was

changed. Right away to the

horizon it was a sea of dusky or

of sunny green, over which the

wind rolled tossing waves of white

keel-shaped flowers with butterfly

wings. Here they were flecked

with violet like bean-blossom,

there with rose like pea-blossom,

and when the wind shook them

together they were lovelier than

the flowers of the loveliest garden

plots.

Luck of the Bean-rows sprang

forward; he recognized it all — the

enlarged field, the improved cabin,

his father and mother alive,

hastening now to meet him as

eagerly as their old limbs would

carry them, to tell him that not a

day had passed since he went

away without their receiving news

of him in the evening, and with

59

the news kindly gifts which had

cheered them, and good hopes of

his return, which had kept them

alive.

The Luck embraced them fondly,

and gave them each an arm to

accompany him to his palace. Now

they wondered more and more as

they approached it! Luck of the

Bean-rows was afraid of

overshadowing their joy, yet he

could not help saying: ‘Ah, if

you had seen Pea-Blossom! But

it is six years since she married.’

‘Since I married you,’ said a

gentle voice, and Pea-Blossom

threw wide the iron gates:

‘My choice was made then, do

you not remember? Do come in,’

she continued, kissing the old man

and the old woman, who could not

take their eyes off her, for she too

60

had grown six years older and was

now sixteen; ‘do come in! This

is your son’s home, and it is in

the land of the spirit and of day

dreams where one no longer grows

old and where no one dies.’

It would have been difficult to

welcome these poor people with

better news.

The marriage festivities were held

with all the splendour befitting

such high personages; and their

lives never ceased to be a perfect

example of love, constancy, and

happiness.

this is the usual lucky ending of

all good fairy tales.