From The Luck of the Bean-Rows, a Fairy-tale for Lucky Children, illustrated by Claud Lovat Fraser, London: Daniel O’Connor, [1921]; pp. 3-40.

ONCE UPON A TIME

there was a man and his wife who

were very poor and very old. They had

never had any children, and this

was a great trouble to them, for

they foresaw that in a few years

more they would not be able to

grow their beans and take them to

market.

One day while they were weeding

in their field (that with a little

cabin was all they possessed — I

wish I owned as much!) — one day,

I say, while they were getting rid

of the weeds the old woman spied in

a corner, where they grew thickest,

a small bundle very carefully tied

up; and what should she find in it

but a lovely boy, eight or ten

months old to look at, but quite

two years in intelligence! He had

been weaned; at all events

he needed no pressing to partake of

boiled beans, which he raised to his

mouth very prettily.

On hearing his wife’s cries of

surprise, the old man hurried from

the end of the field; and when

he too had gazed at the beautiful

child God had given them these

old people embraced each other with

tears of joy, and then returned

quickly to their cabin lest the

falling dew should hurt their boy.

When they were snug in the

chimney corner it was a fresh

delight to them to see the little

fellow reach out his hands to them,

laughing winsomely, and calling

them mamma and pappa, as though

he had known no other father or

mother.

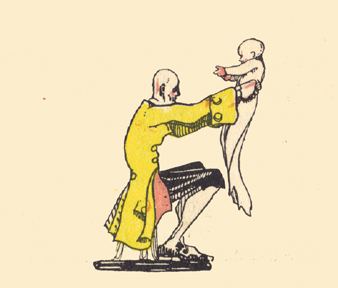

The old man took him on his knee

and danced him gently up and

down, in ‘the way the ladies ride

in the Park,’ and said all sorts of

droll things to amuse him; and the

child responded in his own prattling

fashion, for who would like to seem

backward in such jolly talk?

Meanwhile the old woman lit up

the house with a fire of dry bean-

pods, which gladdened the little

body of the newcomer, and prepared

an excellent bean-pap which

a spoonful of honey made delicious

eating. Then she laid him to sleep

in his fine white night-clothes in

the best bed of bean-chaff in the

house; for these poor folk knew

nothing of feather-beds and

eider-downs. When he was fast

asleep, ‘There is one thing that

bothers me,’ said the old man to

his wife, ‘and that is what we are

to call this bonnie boy, for we

know neither his parents nor

where he comes from.’

‘We must call him,’ said the old

woman, for though she was but a

simple peasant she was quick-

witted, ‘the Luck of the Bean-

rows, for it was in our bean-field

he came to us, the best of luck,

to comfort us in our old age.’

‘There could not be a better

name,’ the old man agreed.

It would make the story too long to

tell what happened in the days and

in all the years that followed; it is

enough to know that the old people

kept getting older and older, while

one could almost see Luck of the

Bean-rows putting on strength and

good looks. Not that he was mighty

of his inches, for at twelve he was

only two and a half feet, and when

he was at work in the bean-field,

of which he was very fond, you

could hardly have seen him from

the road, but his small figure was

so shapely, and he was so winning

in his looks and ways, so gentle, and

yet so sure of his words, and he

appeared so gallant in his sky-blue

smock, red belt, and gay Sunday

bonnet with bean blossoms for

feathers, that people wondered at

him and many believed that he was

really an elf or a fairy.

Many things, I grant, encouraged

this notion. First of all, the cabin

and the bean-field — the bean-field

in which a few years ago a cow

would have found nothing to graze

on — had become one of the fine

estates of the country-side; and

not a soul could tell how it had

happened. Well, to see beanstalks

sprouting, to see them flowering,

to see the blossom fading and the

beans swelling ripe in the pods —

there is nothing out of the common

in that, but to see a whole bean-

field expanding, spreading out,

with never a strip of land added,

whether bought or knavishly taken

from a neighbour’s holding — that

gets beyond understanding.

And all the while the bean-field

went on growing and spreading.

It spread to the south wind, it

spread to the north wind, it spread

towards the dawn, it spread towards

the sunset. And the neigbours

measured their land to no purpose;

they always found it full measure

with a rod or two to the good, so

they naturally concluded that the

10

whole country was getting bigger.

Then again the beans bore so

heavily that the cabin could never

have contained the crop, had it

not also grown larger. And yet for

more than five leagues round the

bean-crop failed, so that beans

had become priceless because of

the quantities sought for the tables

of lords and kings.

In the midst of this abundance

the Luck of the Bean-rows saw

to everything himself, turning the

soil, sorting the seed, cleansing

the plants, weeding, digging,

hoeing, harvesting, shelling, and,

over and above, trimming hedges

and mending wattle-fences. What

time was left he spent bargaining

with the market people, for he

could read, write, and keep accounts,

though he had no schooling.

He was indeed a very blessing of

a boy.

One night, when the Luck was

11

asleep, the old man said to his

wife: ‘There is Luck of the

Bean-rows now, who has done so

much to make us comfortable that

we can spend the few years that

are left us in peace and without

labour. In making him heir to all

we own we have given him only

what is already his; and we

should be thankless indeed if we

did not try to secure him a more

becoming position in life than

that of a bean-merchant. A pity

he is too modest for a professor’s

chair in the universities, and is

just a trifle too short for a general.’

‘It’s a pity,’ said the old woman,

‘he hasn’t studied enough to

pick up the Latin names for five

or six diseases. Eh, but they would

be glad to make him a doctor right

off!

‘Then as to law-suits,’ the old

man went on, ‘I am afraid he has

too much brains and good sense to

clear up one of them.’

;I have always had a fancy,’ said

the old woman, ‘that when he

came of age he would marry

Pea-Blossom.’

‘Pea-Blossom,’ rejoined the old

man, shaking his head, ‘is far

too great a princess to marry a

poor foundling, worth no more

than a cabin and a bean-field.

12

Pea-Blossom, old dear, is a match

for a squire or a justice of the

peace, or for the king himself, if

he came to be a widower. We are

talking of a serious matter, do

speak sense.’

‘Luck of the Bean-rows has more

sense than both of us together,’

said his wife after a moment’s

thought. ‘Besides, it is his

business, and it would not be

proper to press it further without

asking his opinion.’

Whereupon the old couple turned

over and went to sleep.

Day was just breaking when the

Luck leaped out of bed to begin

work in the field as usual. Who but

he was surprised to find his

Sunday clothes laid out on the

chest where he had left his others

at bedtime? ‘It is a week-day,

anyway,’ he said to himself, ‘if

the almanack hasn’t gone wrong.

Mother must be keeping some

holiday of her own to have set out

my best things. Well, let it be as

she wishes. I would not cross her

in anything at her great age, and

after all it is easy to make up for

an hour or two by rising earlier

or working later.’

So after a prayer to God for the

health of his parents and the

progress of the beans, he dressed

13

as handsomely as he could. He

was about to go out of doors, if

only to cast an eye at the fences

before the old couple awoke, when

his mother appeared on the

threshold with a bowl of good

steaming porridge, which she

placed with a wooden spoon on

his little table.

‘Eat it up, eat it up!’ she said;

‘do not be sparing of this porridge

sweetened with honey and a pinch

of green aniseed, just as you liked

it when you were a little fellow;

for the road is before you, laddie,

and it is a long road you will travel

to-day.’

‘That is good to hear,’ said Luck

of the Bean-rows, looking at her

in surprise; ‘and where are you

sending me?’

The old woman sat down on a

stool, and with her two hands on

her knees, replied with a laugh:

‘Into the world, into the wide

world, little Luck. You have never

seen any one but ourselves, and a

few poor market folk you sell your

beans to, to keep the house going,

good lad. Now one day, one day,

you will be a big man if the price

of beans keeps up, so it will be

well for you, dearie, to know some

people in good society. I must tell

you there is a great city four or

five miles away where at every step

one meets lords in cloth of gold

and ladies in silver dresses with

trails of roses. Your bonnie little

face, so pleasant and so lively,

will be sure to win them; and I

shall be much mistaken if the

day goes by without your getting

some distinguished appointment

at Court or in the public offices,

where you may earn much and do

little. So eat it up and do not

spare the good porridge sweetened

with honey and a pinch of green

aniseed.

‘Now as you know more about

the price of beans than about the

value of money,’ the old woman

went on, ‘you are to sell in the

market these six quart measures of

choice beans. I have not put more

lest you should be overburdened.

Besides, with beans as dear as

they are now, you would be hard

15

set to bring home the price even

if they paid you only in gold. So

we propose, father and I, that you

should keep half of what you get

to enjoy yourself properly, as

young people should, or in buying

yourself some pretty trinket to

wear of a Sunday, such as a silver

watch with ruby and emerald seals,

or an ivory cup and ball, or a

Nuremberg humming-top. The

rest of the money you can put in

the bank.

‘So away with you, my little

Luck, since you have finished your

porridge; and be sure that you

do not lose time chasing butterflies,

for we should die broken-hearted

if you were not home before

nightfall. And keep to the roads

for fear of the wolves.’

‘I will do as you bid me, mother,’

replied the Luck of the Bean-rows,

hugging the old woman, ‘though

for my part I would sooner spend

the day in the field. As for wolves,

16

they don’t trouble me with my

weeding-hook.’

So saying he slung his pronged

hoe in his belt, and set out at a

steady pace.

‘Come back early,’ the old

woman kept calling after him; she

was already feeling sorry that she

had let him go.

Luck of the Bean-rows tramped

on and on, taking huge strides like

a five-foot giant, and staring left

and right at the strange things he

saw by the way. He had never

dreamed that the world was so

big and so full of wonders.

When he had walked for an hour

or more, as he reckoned by the

height of the sun, and was puzzled

that he had not yet reached the

great city at the rate he was going,

he thought he heard some one

calling after him: ‘Whoo, whoo,

whoo, whoo, twee! Please do

stop, Master Luck of the Bean-

rows.’

‘Who is it calling me?’ cried

Luck of the Bean-rows, clapping

his hand on his pronged hoe.

‘Please do stop at once. Whoo,

whoo, whoo, whoo, twee! It is I

who am calling you.’

‘Can it be possible?’ asked

Luck, raising his eyes to the top

of an old pine, hollow and half dead,

on which a great owl was swaying

in the wind. ‘What is it we two

can settle together, my bonnie

bird?’

‘It would be indeed a wonder if

you recognized me,’ answered the

owl, ‘for you had no notion that

I was ever helping you, as a

modest and honest owl should, by

devouring at my own risk the

swarms of rats which nibbled

away half your crops, good year

and bad year. That is why your

field now brings you in what will

buy you a pretty kingdom, if you

know when you have enough.

As for me, who have paid dearly

for my care of others, I have not

one wretched lean rat on the hooks

of the larder against daylight, for

now at night, with my eyes grown

so dim in your service, I can

scarcely see where I am going. So

I called to you, generous Luck of

the Bean-rows, to beg of you one

of those good quart measures of

beans hanging from your staff. It

will keep me alive till my oldest

son comes of age, and on his

loyalty to you you may reckon.’

‘Why that, Master-Owl,’ cried

Luck of the Bean-rows, taking

one of his own three quart

measures from the end of his staff,

‘is a debt of gratitude, and I am

glad to repay it.’

The owl darted down on the

measure, caught it in his claws and

beak, and with one flap of the wing

19

carried it off to the tree-top.

‘My word, but you are in a hurry

to be off!’ said the Luck. ‘May

I ask, Master Owl, if I am still

far from the great town mother is

sending me to?’

‘You are just going into it,’

answered the owl, as he flitted off

to another tree.

Luck of the Bean-rows went on

his way with a lighter staff; he

felt sure he must be near the end

of his journey, but he had hardly

gone a hundred steps when he

heard some one else calling:

‘Behh, behh, bekky! Please stop,

Master Luck of the Bean-rows!’

‘I think I know that voice,’ said

the Luck, turning round. ‘Why

yes, of course! It is that bare-faced

rogue of a mountain she-goat,

which prowls around my field with

her kids for a toothsome snack. So

it is you, is it, my lady raider?’

‘What is that about raiding, fair

Master Luck? I guess your hedges

are too thick, your ditches too

deep, your fences too close for

any raiding. All one could do was

to nip a few leaves that pushed

through the chinks of the wattles,

and our pruning makes the stalks

thrive. You know the old saying:

Sheeps’ teeth, loss and trouble,

Goats’ teeth pay back double.’

20

‘Say no more,’ broke in Luck of

the Bean-rows; ‘and may all the

ill I wished you fall upon my own

head. But why did you stop me,

and what can I do to please you,

Madame Doe?’

‘Misery me!’ she sobbed,

dropping big tears, ‘Behh, behh,

bekky! it was to tell you that the

wicked wolf had killed my

husband, the buck; and now my

little orphan and I are in sore

need, for he will forage for us no

more; and I fear my poor little

kid will die of hunger if you

cannot help her. So I called

to you, noble Master Luck of the

Bean-rows, to beg of pity one of

those good quart measures of

beans hanging from your staff. It

will keep us till we get help from

our kinsfolk.’

‘What you ask, Lady Doe,’ said

the Luck, taking one of his two

measures from his staff, ‘is an

act of compassion and good-will,

and I am glad to do it for you.’

The goat caught up the measure

in her lips, and one bound carried

her into the leafy thicket.

‘My word, but you are in a hurry

to be off!’ cried Luck of the

Bean-rows. ‘May I ask you, dear

lady, if I am still far from the

great town mother is sending me

to?’

‘You are there already,’ answered

the goat as she buried herself deep

in the bushes.

Once more the Luck went on his

way, his staff the lighter by two

measures. He was looking

out for the walls of the big town

when he noticed by a rustling

along the skirt of the woods that

some one was following him closely.

He turned quickly towards the

sound, with his pronged hoe

gripped hard in his hand. Well

for him that the prongs were open,

for the prowler that was tracking

was a grim old wolf whose

appaerance promised no good.

‘So it is you, evil beast!’ cried

Luck. ‘You hoped to give me the

place of honour at your evening

spread! By good fortune my two iron

teeth,’ and he glanced at his hoe,

‘are worth all yours together,

though I would not belittle them;

so you may take it as settled, old

crony, that you are to sup this

evening without me. Consider

yourself in luck, too, if I do not

avenge the husband of the she-

goat and the father of the kid

who have been brought into pitiful

straits by your cruelty. Perhaps I

ought to, and it would only be

justice, but I have been brought

up with such a horror of blood

that I am loth to shed even a

wolf’s.’

So far the wolf had listened in

deep humility; now he suddenly

broke into a long and lamentable

howl and turned up his eyes to

heaven as if calling on it to bear

witness.

‘Oh, power divine, who clothed

me as a wolf,’ he sobbed, ‘you

know if ever I felt wicked desires

in my heart. However, my lord,’

he added, with a bow of resignation

towards Luck of the Bean-rows,

‘it lies with you to dispose of my

wretched life. I place it at your

mercy without fear and without

25

remorse. If you think it right

to make my death atone for the

crimes of my race I shall die at

your hands without repining; for

ever since I fondled you in your

cradle with pure delight, when

your lady mother was not there, I

have ever loved you dearly and

truly honoured you. Then you

grew so handsome, so stately,

that, only to look at you, one

might have guessed you would

become a great and magnanimous

prince, as you have. Only I beg

you to believe, before you condemn

me, I did not stain these claws in

the blood of the doe’s luckless

mate.

‘I was brought up on principles of

restraint and moderation — my fell

is sprinkled with grey — but through

all the years I have never swerved

from them. At the time you

mention I was abroad among my

scattered tribesfolk, proclaiming

sound moral doctrines in the hope

of leading them by word and

example to a frugal standard of

living, that high aim of wolfish

character. I will go further, my

lord; that mountain goat was my

good friend. I encouraged

promising qualities in him; often

we travelled together, discoursing

by the way, for he had a bright

26

wit and eagerness to learn. In my

absence a sad quarrel for precedence

(you know how touchy these rock

people are on this point) was the

cause of his death, which I have

never got over.’

The wolf wept — from the very

depth of his heart it seemed, as

inconsolable as the doe herself.

‘For all that and all that,’ said

the Luck of the Bean-rows, who

had kept the prongs of his weeding-

hook open, ‘you were stalking

me.’

‘Following you, following you,

yes,’ replied the wolf in wheedling

tones, ‘in the hope of interesting

you in my benevolent purpose,

but in some more suitable place

than this for conversation. Ah, I

said to myself, if my lord Luck

of the Bean-rows, whose reputation

is spread far and wide, would but

share in my scheme of reform, he

would have to-day a splendid

opportunity. I warrant that one

quart measure of those dainty

beans hanging from his staff would

convert a tribe of wolves, wolflings,

and cubs to a vegetable diet, and

preserve countless generations of

bucks, does, and kids.’

‘It is the last of my measures,’

thought the Luck to himself, ‘but

what do I want with cups and

27

balls, rubies and humming-tops?

And who would put child’s play

before something really useful?

‘There are your beans,’ he said

as he took the last measure his

mother had given him for his

amusement. All the same he did

not shut the prongs of his hoe.

‘It is all that is left of my own,’

said he, ‘but I don’t regret it;

and I shall be grateful to you,

friend wolf, if you put it to the

good use you have promised.’

The wolf snapped his fangs on it

and bounded away to his den.

‘My word,’ said Luck of the

Bean-rows, ‘you are in a hurry

to be off! May I ask, Master Wolf,

if I am still far from the great

town mother is sending me to?’

‘You have been there for long

enough,’ replied the wolf, laughing

out of the corner of his eyes;

‘and stay there a thousand years

you will see nothing new.’

Yet once more Luck of the

Bean-rows went on his way, and

kept looking about for the town

walls, but never a glimpse of them

was to be seen. He was beginning

to feel tired when he was startled

by piercing cries which came from

a leafy by-path. He ran towards

the sound.

‘What is it?’ he shouted, and

gripped his weeding-hook. ‘Who

is it crying for help? Speak; I

cannot see you.’

‘It is I, it is Pea-blossom,’

30

replied a low, sweet voice. ‘Oh,

do come and get me out of this

fix, Master Luck of the Bean-rows.

It is as easy as wishing and will cost

you nothing.’

‘Believe me, madam,’ said the

Luck, ‘it is not my way to count

the cost when I can help. Whatever

I have is yours to command,

except these three quart measures

of beans on my staff; they are

not mine, they belong to father

and mother. Mine I have just

given away to a venerable owl, to

a saintly wolf who is preaching

like a hermit, and to the most

charming of mountain does. I

have not a bean leaf that I can

offer you.’

‘You are laughing at me,’ returned

Pea-Blossom, somewhat displeased.

‘Who spoke of beans, sir? I have

no need for your beans; they

are not known in my household.

The service you can do me is to

turn the door-handle of my carriage

and throw back the hood — it is

nearly smothering me.’

‘I shall be delighted, madam,’

said Luck of the Bean-rows, ‘if

I could only discover your carriage.

No trance of a carriage here! And

no room to drive on such a narrow

path. Still I shall soon find it, for

31

I can hear that you are quite close

to me.’

‘What!’ she cried with a merry

laugh, ‘you cannot see my

carriage! Why, you almost

trampled on it, running up in

your wild way. It is right in front

of you, dear Luck of the Bean-rows.

You can tell it by its elegant

appearance, which is something

like a dwarf pea.’

‘It is so like a chick pea,’ thought

the Luck as he bent down, ‘that

if I hadn’t looked very close I

should have taken it for nothing

but a chick pea.’

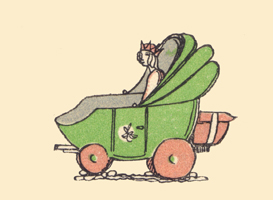

One glance, however, showed him

that it was really a very large

dwarf pea, round as an orange,

yellow as a lemon, mounted on

four little golden wheels, equipped

with a dainty ‘boot,’ or hold-all,

made of a tiny peascod as bright

and green as morocco.

He touched the handle; the door

flew open; and Pea-Blossom

sprang out like a grain of touch-

me-not, and lighted nimbly and

gaily on her feet.

33

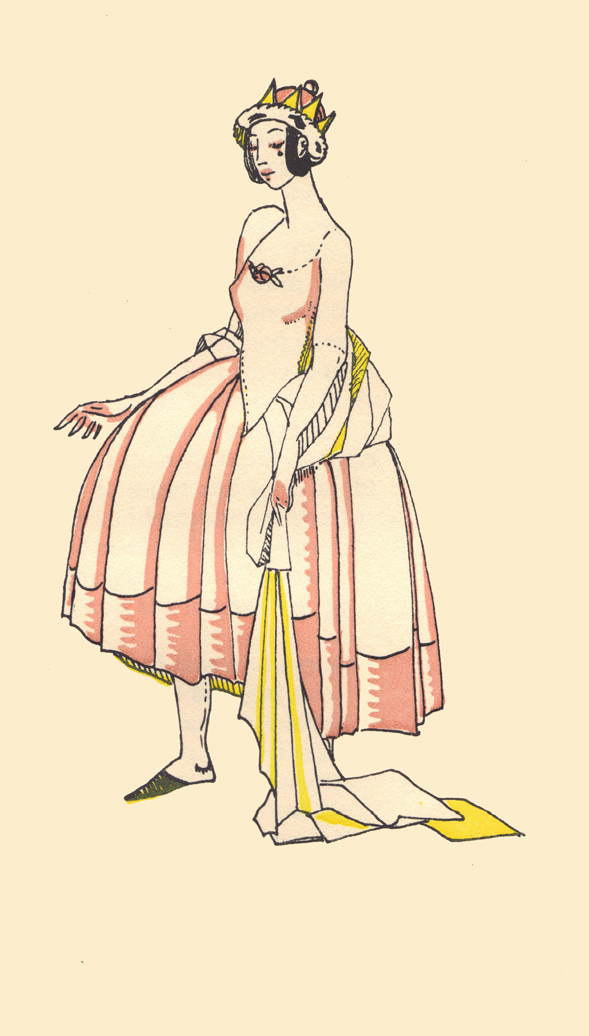

The Luck stood up in amazement;

never had he conceived of any one

so lovely as Pea-Blossom. Her face,

indeed, was the most perfect a

painter could have imagined —

sparkling almond eyes of a

wonderful violet, and a small

frolicsome mouth which showed

glimpses of bright teeth as white

as alabaster. Her short dress,

slightly puffed out and brocaded

with sweet peas, came just below

the knee. She wore tight stockings

of white silk; and her adorable

little feet — why, one envied the

lucky shoemaker who shod them

in satin.

‘What can you be staring at?’

she asked, which shows, by the

way, that Luck of the Bean-rows

was not making a very brilliant

appearance.

The Luck blushed, but quickly

recovered himself. ‘I was

wondering,’ he said modestly,

‘how so beautiful a princess, just

about my own size too, could

possibly find room in a dwarf pea.’

‘What a mistake to speak so

slightingly of my carriage, Luck

of the Bean-rows. It is a most

comfortable carriage when it is

open. And it is quite by chance

that I have not my equerry, my

almoner, my tutor, my secretary,

34

and two or three of my ladies-in-

waiting with me. But I like driving

alone, and this fancy of mine caused

the accident that has happened

to me to-day.

‘I don’t know whether you have

met the king of the crickets in

company; no one could mistake

his glittering black mask, like

Harlequin’s, with two straight

movable horns, and his shrill sing-

song whenever he speaks. The

king of the crickets condescended

to fall in love with me. He is

quite well aware that I come of

age to-day, and that it is the

custom for the princesses of our

house to choose a husband when

they are ten years old. So he put

himself in my way — that too is the

custom — and beset me with a

frightful racket of piercing

declarations. I answered him —

35

also according to custom — by

stopping my ears.’

‘Oh, joy!’ exclaimed the Luck

in rapture. ‘You are not going to

marry the king of the crickets?’

‘I am not going to marry him,’

Pea-Blossom declared with dignity.

‘My choice is made. But no

sooner had I given my decision

than the odious Crik-Crik (that

is his name) flung himself on my

carriage like a wild monster, and

slammed down the hood. “Get

married now, saucy minx,” he

shrieked, “get married if any one

ever comes a-wooing you in this

plight. I don’t care a chick pea

either for your kingdom or

yourself.” ’

‘But do tell me,’ cried Luck of

the Bean-rows indignantly, ‘in

what hole this king of the crickets

is skulking. I will quickly hoe him

out and fling him bound hand and

foot to your mercy. And yet,’ he

continued, as he rested his head

on his hand, ‘I can understand

his desperation. But is it not my

duty, princess, to escort you to

your realm and protect you from

pursuit?’

‘That would certainly be advisable

if I were far from the frontier,’

answered Pea-Blossom, ‘but

yonder is a field of sweet-peas

36

which my enemy dare not

approach, and where I can count

upon my faithful subjects.’

As she spoke she struck the

ground with her foot, and fell,

clinging to two swaying stalks,

which bent under her and then

sprang up again, scattering their

fragrant blossom over her hair.

As Luck of the Bean-rows watched

her with delight — and I assure you

I would have been delighted too —

she pierced him with her bright

eyes, and he was so spell-bound

in the maze of her smile that he

would have been happy to die

watching her. At the least he might

have been still standing there had

she not spoken.

‘I have delayed you too long

already,’ she said, ‘for I know

what a stirring business the trade

in beans must be just at present;

but my carriage — or rather your

carriage — will enable you to

recover the time you have lost.

Please do not hurt my feelings

by refusing so slight a gift. I have a

thousand carriages like it in the

corn-lofts of the castle, and when

I would like a new one I pick it

out of a handful and throw the

rest to the mice.’

‘The least of your highness’s

favours would be the pride and

joy of my life,’ replied the Luck

of the Bean-rows, ‘but you have

forgotten that I have luggage. I

can easily imagine that however

closely my bean measures may be

filled I could manage to find room

for your carriage in one of them,

but to get my measure into your

carriage, that would be impossible.’

‘Try it,’ laughed the princess as

she swung up and down on the

sprays of the sweet-peas; ‘try it,

and do not stand amazed at

everything, as if you were a little

child who had seen nothing.’

And indeed Luck of the Bean-

rows had no difficulty in getting

his three quart-measures into the

body of the carriage — it could

have held thirty and more, and he

felt rather mortified.

‘I am ready to start, madam,’

he said, as he took his place on a

plump cushion, which was large

enough to let him sit comfortably

in any position, or even to lie at

full length if he had been so

minded.

‘I owe it to my kind parents,’

he continued, ‘not to leave them

in suspense as to what has become

of me this first time of my ever

leaving them; so I am waiting

only for your coachmen, who fled,

no doubt in terror at the outbreak

of the king of the crickets, and

took the horses and shafts with

him. I shall then leave this spot

with everlasting regret that I

should have seen you without

hope of ever seeing you again.’

The princess did not appear to

notice the marked feeling of the

Luck’s last words.

‘Why,’ she said, ‘my carriage

39

does not need either coachman,

shafts, or horses; it goes by

steam, and at any hour it can

easily do fifty thousand miles.

You see you will have no trouble

in getting home whenever it suits

you. You have just to remember

the gesture and words with which

I start it.

‘In the boot you will find various

things that may be useful on the

journey; they are every one of

them yours. You open the boot as

you would shell a green pea. There

you will see three caskets, the

shape and size of a pea, each

fastened by a thread which keeps

them in their cases like peas in a

pod, so that they cannot jolt

against each other when you travel

or when you remove them. It is a

wonderful contrivance!

‘They will open at the pressure

of your finger — like the hood of

my carriage. Then all you have to

do is to make a hole in the ground

with your hoe, and sow some of

their contents in it, to see whatever

you may wish spring up, sprout

and blossom. Is not that wonderful?

‘Only remember this! — when

the third casket is empty I have

nothing else to offer you; for I

have only three green peas, just

as you had three measures of

40

beans; and the prettiest girl in

the world can give you no more

than she has.

‘Are you ready to set out now?’

The Luck of the Bean-rows bowed;

he felt that he could not speak.

Pea-Blossom snapped her thumb

and middle finger: ‘Off, chick

pea!’ she cried; and the field of

sweet-peas was left nine hundred

miles behind, while Luck of the

Bean-rows was still turning this

way and that, looking in vain for

Pea-Blossom.

‘Alas!’ he sighed.