<><><><><><><><><><><>

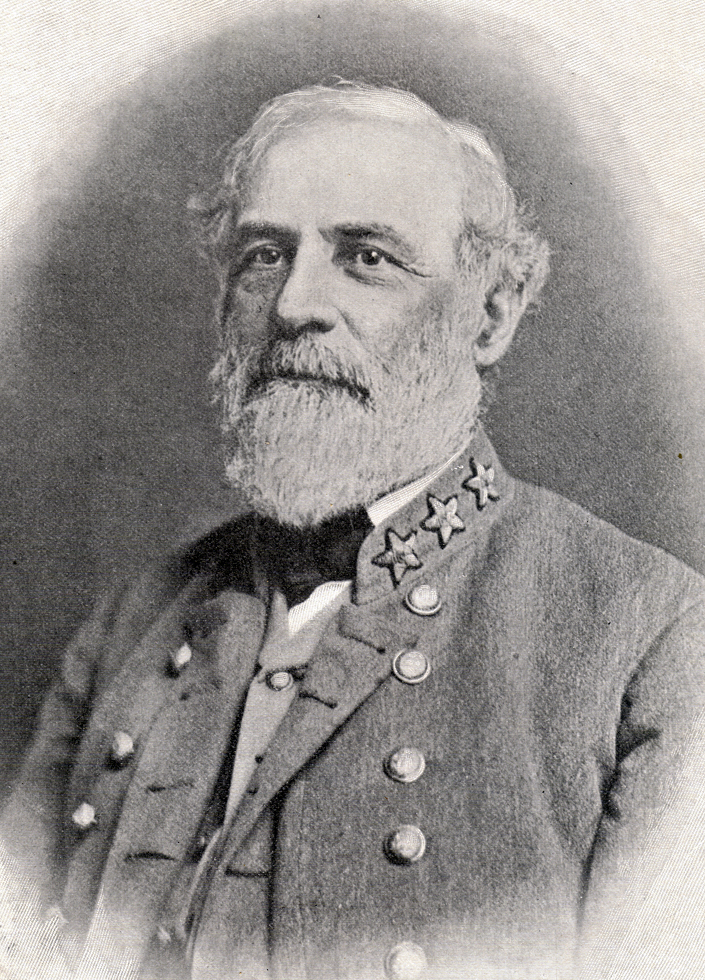

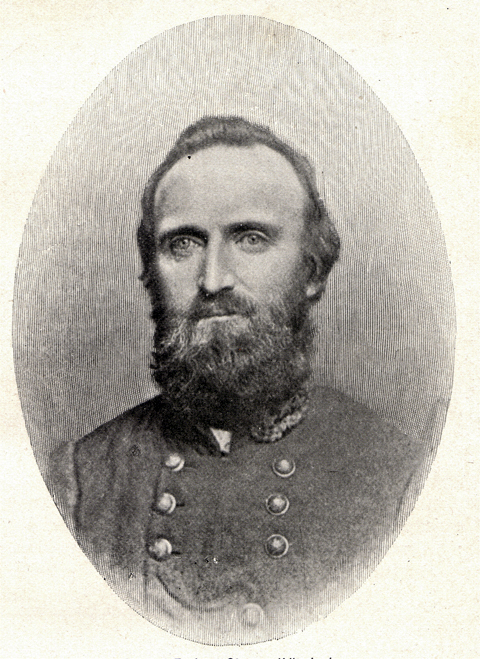

General Lee.

345LEE OF VIRGINIA.

I. — FROM THE DEFENCE OF RICHMOND (1862) TO THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG.

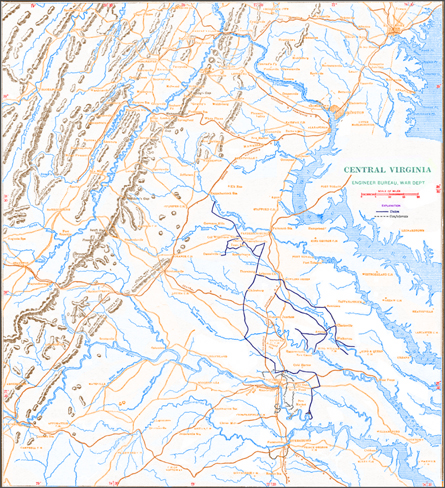

Map of Central Virginia, adapted for the internet by Bill Thayer.

© September, 2009.

Enlarged version available here.

(It will open in a new browser window.)

GENERAL LEE died peacefully at his home in Lexington, Virginia, on October 12th, 1870, being then in the sixty-third year of his age. More than five years had elapsed since war had ceased with the last gun at Appomattox; and from the culminating anguish of that day, so bravely borne, yet in his proud heart more than the bitterness of a thousand deaths, he had retired to the little college town in the Valley of Virginia, there to find the unfailing solace of a deeply religious nature walking habitually nearer to his God, and, as President of the Washington College, to devote the remainder of his life to “bringing these young men to Christ.” Thus, in the too brief period of calm 346 that preceded his passing, his character took on that “look southward, and was open to the beneficent noon of Nature and Deity.” It was in such aspect that he died. The last heart-tributes of tears from the men, women and children of the South, of silent and reverential sympathy from the North, were paid rather to the Christian gentleman and beloved friend than to the soldier chieftain, the martial hero of American chivalry.

Yet it is as a soldier that Lee will stand immortal in history. His name is written upon the same brief scroll that contains those of Cæsar, Hannibal, Marlborough, Frederick, Napoleon. It is one of the four that America blazons highest upon her Pantheon of war — Washington, Lee, Grant, Scott.

The time is not yet come, indeed, for a deliberate and final estimate of Lee. It is not for us of the present day to adjust the historical perspective through which posterity shall view his genius and achievements. But it is our especial opportunity and dutiful task to fix the actual record and true presentment of fact upon which the future legend must rest. Lee himself wrote, after the close of the war, “It will be difficult to make the world believe the odds against which we fought.” The one authentic source of information lies in contemporary official testimony — in the personal statements of those who prominently participated, on both sides, in the events reviewed. The facilities now at hand for the collation of such testimony, in the case of General Lee, are exceptional. Within a single generation, since the war ended, all of the great principals in the conflict have passed away. With the exception of the federal General Rosecrans, not a single general who commanded an army on either side in any of the great battles of the war is living to-day. Nearly all of the dead warriors and statesmen who were prominently connected with the struggle have left their published memoirs. These undoubtedly, are strongly partisan on 347 their respective sides; but the eternal verity dwells in the sober balance between their over-statements.

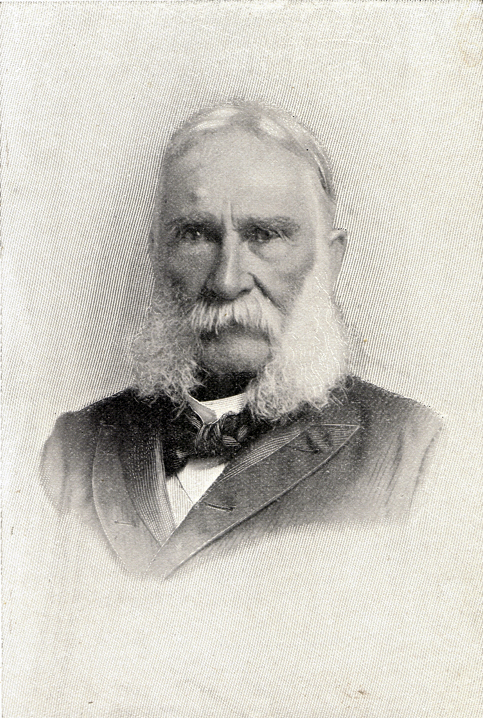

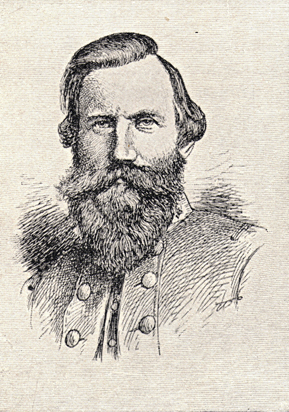

General Fitzhugh Lee, Nephew, and Cavalry Commander of

General Robert E. Lee.

General Grant penned his “Personal Memoirs” under the very shadow of death, with Fate at his elbow, and the dying seal of truth upon his always frank and dispassionate lips. General Lee, who never wrote anything about his own career and campaigns, had nevertheless intended to record the deeds of his soldiers; but he waited for a “convenient season,” and waited too long. Of his chief lieutenants, however, his corps commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia, two survive to speak of the mighty past in no uncertain tones, though from different points of view. These two are General Fitzhugh Lee (nephew of the Confederate chieftain, and his cavalry commander after the death of Stuart), who in his military biography of General Lee gives with intimate authority his impressions, opinions and reports upon the momentous events with which he was so closely connected; and General James Longstreet, whose volume entitled “From Manassas to Appomattox” is probably the last that will be contributed to the history of the American Secession War by any of the principal actors therein.

General James Longstreet (in 1888).

It is by no means the pretension, in the four brief chapters herewith begun, to present either a personal biography or a full military appreciation of General Lee, summarising the various material indicated as being now available. The purpose, far less assuming, is to offer a king of animated picture, or reproduced impression, as accurate and vivid as may be, of the foremost American soldier, in action, at the climax of his career. To this end, portraits and other illustrative matter, hitherto for the most part unpublished, will figure in important measure; and in the same “pictorial” spirit, certain new and well-authenticated personal anecdotes, which seem characteristic, will be introduced : the final result being, it is hoped, a presentment of something like the real “Lee of Virginia,” in his grand traits and in his habit as he lived.

I.

THE SEVEN DAYS’ BATTLES WITH M‘CLELLAN, IN FRONT OF RICHMOND.

IN April 1861, when the first gun of the Civil War was fired upon Fort Sumter, Robert Edward Lee, of Virginia, fifty-four years old, was Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry in the United states Army. He had seen thirty-two years’ honourable service in that army, including the campaign of Mexico. There, as an officer of Engineers, on the staff of General Winfield Scott, he had won high distinction, — so much so, that General Scott, when subsequently brevet Lieutenant-General, said : “It is my deliberate conviction, from a full knowledge of his extraordinary abilities, that if the occasion ever arises Lee will win his place in the estimation of the whole world.” And the old General added, enthusiastically, “I tell you, sir, Robert E. Lee is the greatest soldier now living, and if he ever gets the opportunity he will prove himself the great captain of history.”

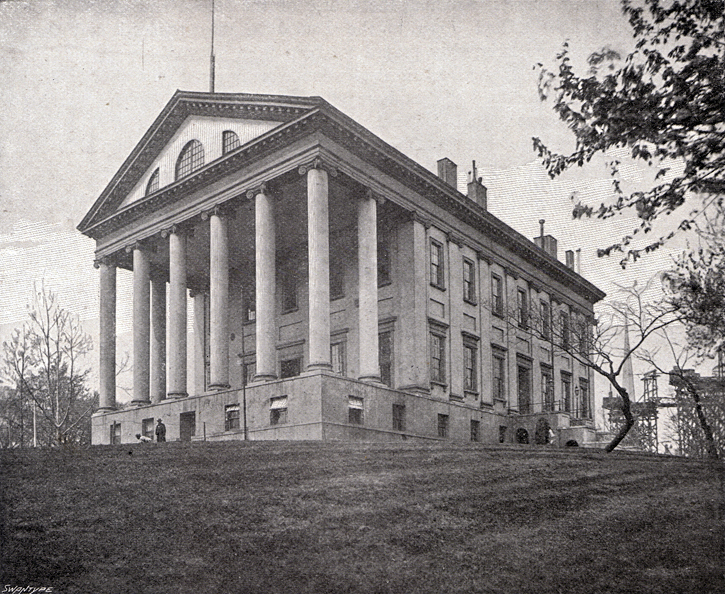

The secession of South Carolina, Georgia, and the Gulf States from the Union had been followed by that of Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi, had been elected, at Montgomery, Alabama, President of the Confederate States. Finally, on April 17th, 1861, the Ordinance of Secession was passed by the Virginia Convention assembled in the old Capitol building at Richmond.

The veteran General Scott held the chief command of the United States Army, after more than half a century of continuous service therein; and, though a Virginian by birth, he refused to follow the mother state in her withdrawal from the Union. Naturally he strove to influence Lee to the same conclusion. To make the argument irresistible, while at the same time in perfect consistency with his previously expressed estimate of his distinguished lieutenant, General Scott exerted his powerful influence with President Lincoln, with the result that Lee was offered, through Francis Preston Blair, the succession to his own (Scott’s) commission in chief command of the Federal army.

Colonel Lee, it should be remembered, was from the first and always opposed to secession, and he deplored the necessity of war. “If I owned the four million slaves,” he declared, “I would give them all to the Union.” Leaving out of the question the magnificent inducement offered through the influence of his old commander, every consideration of self-interest, to say nothing of personal convictions and sympathies, would have prompted him to take the Federal side. Nor can it be doubted that, with his experienced judgment and knowledge of the national military resources, he saw from the outset that the Confederacy was embarking upon what must prove eventually a lost cause.

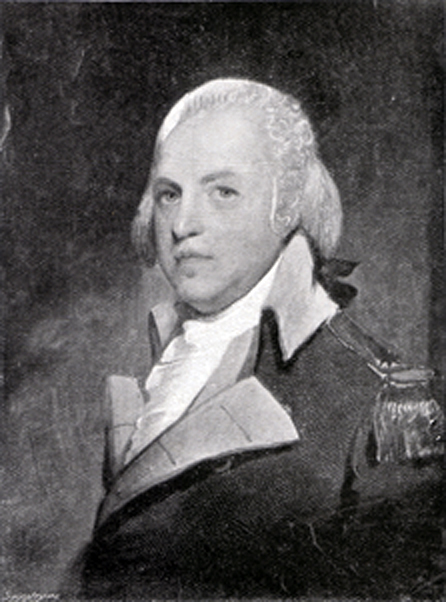

Major-General Henry Lee (“Light-Horse Harry,” etc.).

But a Lee could not hesitate here. To quote his own undying phrase, “Duty is the sublimest word in our language.” With Dante, he would have relegated to the vestibule of the Inferno, as a spectacle for the everlasting contempt of gods and men, those who in time of civil war sought escape from the dangers and responsibilities of citizenship by shirking the discharge of their highest obligation. In 1792, his own gallant father, the “Light-Horse Harry” of the Revolution, had said at a similar crisis : “No consideration on earth could induce me to act a part, however gratifying to me, which could be construed into disregard of faithlessness to this Commonwealth.” Robert Lee, in April 1861, having formally resigned his commission in the United States Army, wrote :—

“With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an 349 American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home.”

And when, immediately after this resignation, Virginia called him to the chief command of her forces by land and sea, he accepted it with these words :—

“Trusting in Almighty God, an approving conscience, and the aid of my fellow-citizens, I devote myself to the service of my native state, in whose behalf alone will I ever again draw my sword.

The exalted moral conviction with which Lee entered the arena of this mighty struggle is scarcely paralleled in the chronicles of knighthood and war. It is in the light of this, and of this only, that his subsequent achievements can be accounted for and understood.

Jefferson Davis, the provisional President of the new Confederate States Government, proceeded from Alabama to Virginia in the latter part of May 1861, and took up his residence in Richmond, which became the capital of the Confederacy. At the same time the advance-guard of the Federal Army of the Potomac, under General McDowell, crossed the river from Washington, and took up its first headquarters on Virginian soil at Arlington Heights, the historic home which General Lee had but lately quitted. The objective point of this army of invasion was Richmond, 115 miles to the south, the capture of which might speedily break the force of the rebellion and terminate the war.

General Lee immediately set to work, with his quiet energy and masterful skill, to organisc, drill, and equip the raw recruits as they poured into Richmond from the Southern States. He virtually created the army of Northern Virginia, having no nucleus of “regulars” to work upon, no commissary, quartermaster’s, or ordnance departments, no cavalry, arms, or equipments, and scarcely any artillery. His strategic genius predicted the probable line of the Federal advance upon Richmond, and pointed out Manassas Junction (Bull Run), thirty miles west-south-west of Washington, as the first battlefield. The phenomenal victory gained there on July 21st, by the Confederate army under Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston, was acknowledged to be in large measure due to the admirable condition in which General Lee sent his newly organised troops to the field.

Prevented by his duties in Richmond from participating in person, as he would have desired, in the battle of Manassas, General Lee made his first appearance in the field as a commander of troops in the early part of August, when he was sent 350 to Western Virginia to take charge of an army there, consisting of some six thousand men, pitted in the mountain passes against ten thousand Federals commanded by General Rosecrans, seeking, what they eventually obtained, the alliance of that doubtful territory. His two months’ campaign there was not marked by any defeat or disaster, and did finally check the advance of Rosecrans; yet it was indecisive, and disappointed public expectation.

General Robert E. Lee in field uniform.

(This portrait was taken expressly for Her Majesty Queen Victoria.)

The President of the Confederate States, however, and the Governor of Virginia, never wavered then or afterwards in their optimistic faith in Lee. The General himself returned quietly to Richmond to resume his duties under the eye of the Chief Executive, and, calmly confident alike of present and future, made no response to public criticisms. In November he was sent south to look after the Atlantic coast defences of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. It was this period that Paul H. Hayne, the distinguished Southern poet, meeting him at Fort Sumter, Charleston, recorded his personal impression in language worthy to stand as the classic pen-portrait of the noble Virginian :—

“Leaning against a great columbiad which occupied an upper tier of the fortress, we were engaged in watching the sunset, when voices and footsteps attracted our notice. Glancing round, we saw approaching us the then commander of the place, accompanied by several of his captains and lieutenants; and, in the middle of the group, topping the tallest by half a head, was perhaps the most striking figure we had ever encountered, — the figure of a man seemingly about fifty-six years of age, erect as a poplar, yet lithe and graceful, with broad shoulders well thrown back, a fine, justly-proportioned head posed in unconscious dignity, clear, deep, thoughtful eyes, and the quiet, dauntless step of one every inch the gentleman and soldier. Had some old English cathedral crypt or monumental stone in Westminster Abbey been smitten by a magician’s wand and made to yield up its knightly tenant restored to his manly vigour, with a chivalric soul beaming from every feature — some grand old Crusader or Red Cross warrior who, believing in 35 a sacred creed and espousing a glorious principle, looked upon mere life as nothing in the comparison — we thought that thus he would have appeared, unchanged in aught but costume and surroundings. This superb soldier, with the glamour of the antique days about him, was none other than Robert E. Lee, just commissioned by the President, after his unfortunate campaign in Western Virginia, to travel southward and examine the condition of our coast fortifications.”

With the opening of the spring of 1862, preparations for active military operations began in fearful earnest : at the north, for an overwhelming attack upon Richmond; at the south, for a determined defence of that capital. Early in March President Davis called General Lee home from the Southern Department to assign him to the position of Commander of the armies of the Confederacy, and charged with the duty of conducting all their military operations, under his (the President’s) direction. In the meantime, Northern Virginia had been formed into a new military department, under General J. E. Johnson’s command, extending from the Allegheny Mountains on the west to the Chesapeake Bay on the east, and divided into three districts : the Valley, to be commanded by Thomas Jonathan (“Stonewall”) Jackson; the district of the Potomac, under Beauregard; and the section around Aquia Creek, on the right banks of the lower Potomac, under Major-General Holmes. In March 1862, this entire army, including Jackson’s force in the valley and the few regiments under Holmes at Aquia Creek, numbered barely fifty thousand; while General M‘Clellan’s report shows the Federal army in Washington at the same time, swollen with the troops that had poured into the Department ever since the “Bull Run” disaster, to have had no less than 171,602 men present for duty.

![Engraving of a portrait of General George B. M'Clellan [McClellan] in civilian clothes, a black suit and loose bow-tie.](../../../images/LeeP351PicF-auto.jpg)

General George B. M’Clellan, U.S.A..

M‘Clellan had well-grounded objections to invading Virginia by the Manassas route, as McDowell had done. He preferred to take his army down the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, and, with Fortress Monroe as a base, to move up the peninsula between the estuaries of the James and the York, with his gunboats on those rivers protecting his flanks. The adoption of this plan was decided by the final retirement of the Confederate army which had been threatening Washington, and the raising of the blockade of the Potomac. General Johnston had made this retrograde movement to the line of the Rappahannock, so as to be near enough to Richmond to promptly meet a Federal advance upon the city, from whatever direction it might come.

M‘Clellan’s army was therefore transferred to the Peninsula early in April, at which time General J. B. Magruder occupied it with about eight thousand men, soon reinforced to twenty thousand. General Johnston was then assigned to the 352 command of that department; and upon looking over the ground, he advised the immediate abandonment of the Peninsula and the evacuation of Norfolk. President Davis, however, after a conference with his Secretary of War and General Lee, decided to resist M‘Clellan on the Peninsula. This resistance delayed the Federal advance for a month, giving time to strengthen the works around Richmond, in preparation for the inevitable battle there. Then followed Johnston’s evacuation of Yorktown and the Warwick River line, the battle of Williamsburg, and the stubborn retreat of the Confederate army up the Peninsula. The seat of war was transferred to the Chickahominy, in the vicinity of Richmond.

The Chickahominy is a small river which, from its source north-west of Richmond, flows in an easterly and then in a south-easterly direction, sometimes within four or five miles of that city, and finally empties into the James thirty miles below. It is a narrow, deep, sluggish stream, bordered by marshlands and tangled woods. All the roads radiating from Richmond to the north and east, especially in the direction of the Peninsula, cross the Chickahominy over various bridges : Meadow Bridge, New Bridge (opposite Gaines’ Mill), Bottom Bridge, Long Bridge, etc.

General M‘Clellan had crossed the swollen Chickahominy with a portion of his army, and, at the end of May, lay on both sides of that stream, with headquarters at Gaines’ Mill. His army numbered about 105,000 effectives, while the Confederates under Johnston numbered 62,696. In this locality, and under the conditions stated, the battle of Seven Pines (known to Federal historians as Fair Oaks) was fought, on May 31st and June 1st. It was an indecisive affair, and costly to both sides, without glory to either; but a sufficient check was administered to M‘Clellan not only to stop his advance but to put him hors de combat for nearly a month, during which time the preparations for defence could be completed.

In this battle of Seven Pines, General “Joe” Johnston was severely wounded, and the command of the army devolved upon General Gustavus W. Smith, the officer next in rank. But General Smith being in feeble health, and not in fit condition for further active service, he was relieved the next day; and the Confederate President, with the approval of his Cabinet, assigned General Robert E. Lee to the command in the field of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Thus, on the 1st day of June, 1862, one year after the beginning of the war, General Lee assumed active command of that superb army which he himself had organised, and which thereafter he was to lead, within a space of less than three years, through victory and defeat, against fate and amidst overwhelming disaster, to immortal fame.

That the succession of Lee to this command did not carry with it at the time the absolute prestige which his name subsequently acquired, is indicated by the comment of General Longstreet. That able but cross-grained officer, in his published reminiscences, begins his series of subtly disparaging asseverations, leading up to the notorious Gettysburg impeachment, as follows :—

“The assignment of General Lee to command the Army of Northern Virginia was far from reconciling the troops to the loss of our beloved chief, Joseph E. Johnston. . . . General Lee’s experience in active field work was limited to his West Virginia campaign against General Rosecrans, which was not successful. His services on our coast defences were known as able, and those who knew him in Mexico as one of the principal engineers of General Scott’s column marching for the capture of the capital of that great republic, knew that as a military engineer he was especially distinguished. But officers of the line are not apt to look to the staff in choosing leaders of soldiers, either in tactics or strategy. There were, therefore, some misgivings as to the power and skill for field-service of the new commander.”

353Whatever his qualifications and prestige, the situation that confronted the new commander at this crisis was appalling. An enemy of formidable strength was at the gates of Richmond, and was reaching out with his right for an expected junction with the army of McDowell, which the Federal Government had reluctantly consented to withdraw from the protection of Washington and send to reinforce M‘Clellan.

The very first consultation between President Davis and General Lee, as they rode out to the army on the day after the latter assumed command, is highly characteristic; and shows as by a lightning flash the swiftness, clearness, and audacity with which the great soldier developed his plan of action. General Lee had just come from a conference with a number of his general officers, who had taken a very despondent tone, predicted that the enemy would inevitably get into Richmond, and were for abandoning all attempt to maintain a line of defence north of the James River. General Lee had answered, with more feeling than he was accustomed to betray, that such a course of argument, pursued to its legitimate results, would leave him nothing except gradually to fall back to the Gulf of Mexico.

What he proposed to do, he told President Davis, was to take up the plan of defence which General Johnston was to have executed, with one important additional feature : it would be necessary to bring on the stronger force of General T. J. Jackson from the Valley of the Shenandoah. “Stonewall” was at that moment hotly engaged with a force superior to his own, which must be driven out of the Valley before he could be withdrawn. In order to mask the design of joining Jackson’s forces with those of Lee in front of Richmond, a strong division should first be sent to help Jackson drive the enemy across the Potomac. This division was to be detached in such an open and ostentatious manner that M‘Clellan would be sure to hear of it, and be deceived as to its eventual motive. At the same time it would probably confirm him in his exaggerated estimate of the Confederate strength; for “Little Mac” had already developd in a marked degree that singular megalomania which caused him then and afterwards, when confronted by Lee, to count the latter’s force in at least double its real numbers.

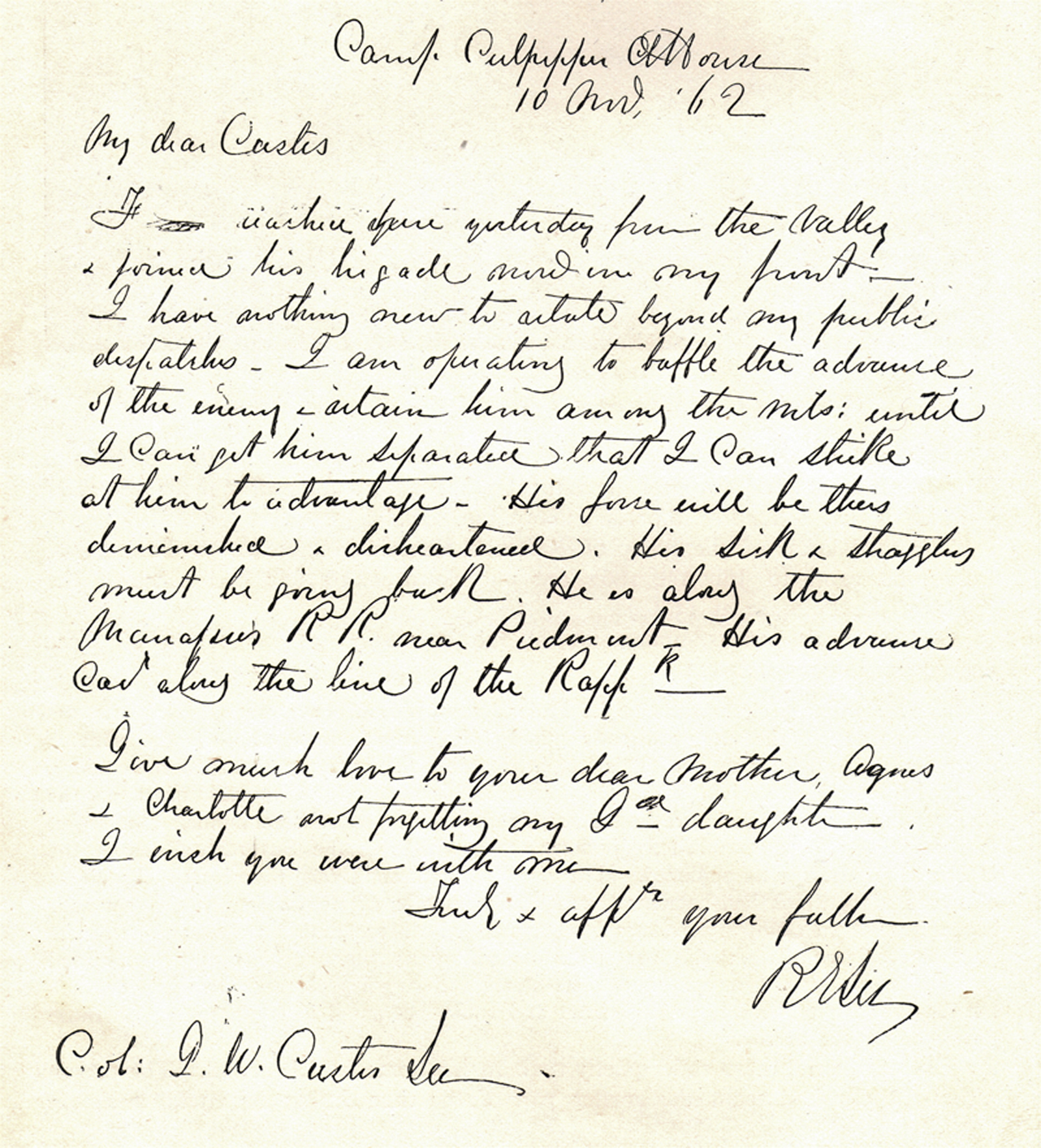

General T. J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson.

(Last portrait from life.)

Lee planned to throw forward his left across the Chickahominy at Meadow 354 Bridge, drive back the enemy’s right, while Jackson descended upon its rear, and then, crossing farther down at Mechanicsville with another column, to attack in front. The chief danger, President Davis thought, was that the Confederate force and intrenched line between that left flank and Richmond might prove too weak to stand a possible assault.

“If M‘Clellan is the man I took him for when I nominated him for promotion in the cavalry, and subsequently selected him to go with the military commission to the Crimea, as soon as he finds the bulk of our army on the north side of the Chickahominy he won’t stop to try conclusions, but will immediately move upon Richmond. But if, on the other hand, he should behave like an engineer officer, and deem it his first duty to protect his line of communication, then I think the plan proposed is not only the best, but will succeed.”

Something of the old esprit de corps manifested itself in General Lee’s immediate response, that the “did not know engineer officers were more likely than others to make such mistakes.” But, passing on to the main subject, he added:

“If you will hold him as long as you can at the intrenchments, and then fall back on the detached works around the city, I will be upon the enemy’s heels before he gets there.” (Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.)

To locate the enemy’s lines, and blaze the way for Stonewall Jackson’s descent and his own attack upon his right, General Lee, on June 11th, despatched his cavalry commander, the dashing J. E. B. Stuart, with 1200 troopers, on the expedition which developed into the celebrated “raid” completely around the right, rear, and left of M‘Clellan’s army of 115,000 men in line of battle.

General J. E. B. Stuart.

On the same day he wrote to General Jackson :

“The object is to enable you to crush the forces opposed to you, then leave your unavailable troops to watch the country, and with your main body move rapidly to Ashland, and sweep down between the Chickahominy and Pamunkey, cutting up the enemy’s communications, while this army attacks General M‘Clellan in front.”

Thomas Jonathan Jackson, surnamed “Stonewall,” and now in the thirty-eighth year of his age, was just winding up that series of brilliant and victorious operations in the Valley which raised him in the space of a single year from an obscure professor in the Virginia Military Institute to a blazing meteor of battle and a terror to the armies of the foe. With him, when the sword was drawn the scabbard was thrown away. In rapid and bewildering succession he had scattered and defeated the forces of Banks, Fremont, Milroy and Shields, “holding one commander at arm’s length while he hammered the others.” In three months he had marched six hundred miles, fought four pitched battles, seven minor engagements, and daily skirmishes; defeated four armies, captured seven pieces of artillery, ten thousand stand of arms, four thousand prisoners, and an immense quantity of stores. So great was the alarm excited in Washington by the movements of this “ubiquitous 355 Presbyterian,” that McDowell’s army, instead of going to reinforce M‘Clellan, as expected, was diverted to the Valley, thus very materially relieving the pressure upon Richmond.

“Old Stonewall,” preceding his army, reached Richmond by an all-night ride on June 23rd, and participated in a conference called by General Lee, of the other commanding officers of divisions — Longstreet, D. H. Hill, and A. P. Hill — who were to attack M‘Clellan’s right. Jackson’s troops were all up and encamped at Ashland, fifteen miles north of Richmond, on the night of the 25th.

“Stonewall” Jackson—Joseph E. Johnston—Robert E. Lee..

General Lee’s battle order directed that Jackson’s command should “proceed from Ashland” on Wednesday, the 25th, to be ready on the day following to fall upon the Federal right flank, simultaneously with A. P. Hill’s and Longstreet’s 356 attack in front, at Mechanicsville. But as Jackson — being unexpectedly and no doubt unavoidably retarded — did not reach Ashland until the evening of the 25th, he could not “proceed from” that point until Thursday, the morning set for the attack. He was, therefore, practically a day behind time. This delay, while it did not prevent the successful carrying out of Lee’s programme, added heavily to the cost of its execution — for in those early days the Virginians were too lavish of blood, and, as General Fitzhugh Lee says, “thought it a great thing to charge a battery of artillery or line of earthenworks with infantry.” On that eventful Thursday, Lee’s eager troops were up in line of battle before Mechanicsville, and the Confederate commander had no choice but to go on with the attack. A. P. Hill waited until three o’clock in the afternoon, then proceeded to drive the Federals out of Mechanicsville, and to batter at their strongly intrenched lines on Beaver Dam — a little stream emptying into the Chickahominy, a mile below. All the time he looked round for Jackson to sweep around on his left, but he looked in vain. The next morning, however, the 27th, “Old Stonewall” flanked the Federals on Beaver Dam Creek, and they were forced with great slaughter to the banks of the Chickahominy, which they crossed during the night; so that on the morning of the 28th M‘Clellan’s whole army was on the south side of that stream, where Lee was waiting for him with his right wing under Huger and Magruder. The battle of Gaines’ Mill being fought and won, and the purpose of the Union commander — to retreat to the James by the nearest practicable route — discovered, General Lee on the 29th united his entire army south of the Chickahominy. There he attacked the retreating enemy near Savage Station, the same afternoon; and the next day, the 30th, overtook them again a Frazier’s Farm. This sanguinary battle was fought by Longstreet and A. P. Hill; Huger and Jackson being retarded by the difficult passage through the White Oak Swamp. However, as General Lee’s report says, the enemy was driven from every position but one, from which he afterward withdrew under cover of darkness.

Jackson came up on July 1st, and was sent on down the Willis Church road in pursuit of the enemy. M‘Clellan had concentrated his artillery, and occupied a position of great strength on the rise of Malvern Hill, within sight of the James River. Immediately in his front was open ground, sloping downward for half a mile, and completely covered by the fire of his infantry and artillery. General Lee says, —

“To reach this open ground our troops had to advance through a broken and thickly wooded country, traversed nearly throughout its whole extent by a swamp passable at but few places, difficult at those. The whole was in range of the batteries on the heights and the gunboats on the river, under whose incessant fire our movements had to be executed.”

Certainly General M‘Clellan was conducting his “change of base,” as he called this retreat to the James, with masterly skill, selecting his positions unerringly, and defending them well. Malvern Hill was his last desperate stand.

He was hotly assaulted here by portions of Jackson’s, D. H. Hill’s, Magruder’s and Huger’s divisions; but the attack failed to break his line, and at nightfall the Confederate columns retired without having dislodged the enemy. The Union troops, however, again retreated during the night, and succeeded in reaching the protection of their gunboats on the James River at Westover, where General Lee deemed it inexpedient to attack, with his exhausted troops, and in the midst of a violent storm. The next day M‘Clellan had his shattered army in security at Harrison’s landing.

The impression made upon M‘Clellan by the fighting of the Army of Northern 357 Virginia under Lee, may be judged by the fact that in his report to the Federal War Department on June 26th he estimates the latter’s force at “about 180,000” — which is just a hundred thousand above the actual figure.

The total losses of the Army of Northern Virginia in these seven days’ fights, from June 22nd to July 1st, 1862, are put down at 16,782; and those of the Army of the Potomac at 15, 849.

The old Capitol at Richmond, Va.

(Designed by Thomas Jefferson after the model of the Maison Carrée at Nimes.)

General Lee’s own summing up, at the conclusion of his report of these engagements, is as follows :

“Under ordinary circumstances the Federal army should have been destroyed. Its escape was due to the causes already stated. Prominent among these is the want of correct and timely information. This fact, attributable chiefly to the nature of the country, enabled General M‘Clellan skilfully to conceal his retreat, and to add much to the obstructions with which Nature had beset the way of our pursuing columns. But regret that more was not accomplished gives way to gratitude to the Sovereign Ruler of the Universe for the results achieved. The siege of Richmond was raised, and the object of a campaign, which had been prosecuted after months of preparation at an enormous expenditure of men and money, completely frustrated. More than ten thousand prisoners (including officers of rank), fifty-two pieces of artillery, and upward of thirty-five thousand stand of small arms, were captured. The stores and supplies of every description which fell into our hands were great in amount and value, but small in comparison with those destroyed by the enemy.”

The conquering hero rode quietly back to his home in Richmond. The people within the city had spent the greater part of the time during the fateful week on 358 the roofs of their houses, watching the course of the smoke and gleam of battle. “As the lurid light drifted down to the Peninsula, they rejoiced and thanked God; when it shone nearer, they prayed for help from above.”

Lee as a commander had silenced all doubters, inspired his antagonists with wholesome awe, and justified the fondest hopes of those by whom he was trusted and beloved. A letter from Colonel R. H. Chilton, Adjutant and Inspector-General of the Armies of the Confederacy, is representative of the opinion of the administration and military men generally :—

“I consider General Lee’s exhibition of grand and administrative talents and indomitable energy, in bringing up the army in so short a time to that state of discipline which maintained aggregation during those terrible seven days’ fights around Richmond, as probably his grandest achievement.”

HENRY TYRRELL.

<><><><><><><><><><><>