~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

From Highlights of Foreign Travel, A Memorable Journey to Palestine, Egypt, Italy, and the Battle Front of France, by Henry Howard Harper, with Illustrations by Haydon Jones, New York: Brentano’s Publishers, 1925; pp. 7-55.

HIGHLIGHTS OF FOREIGN TRAVEL,

by

Henry Howard Harper,

with

Illustrations by Haydon Jones.

A MEMORABLE JOURNEY

Our first stopping place out of New York was the tropical Island of Madeira, where we spent but one day. We were driven over the rough cobblestones through the town on sleds drawn by oxen to the foot of the mountain, where we took the corrugated railroad to the top. On our way up the train was accompanied by the customary relays of children who run alongside the open cars with bunches of wild-flowers which they throw into the laps of the passengers, expecting pennies in return. I observed that they sometimes threw their flowers into the laps of half a dozen persons and had them returned as many times before finding one who would accept them. But every time they threw them they clung to their position in the procession with bulldog tenacity until either the bouquet or the money was returned. Occasionally they were crowded out, or stumbled [ 8 ] and fell by the wayside, meaning the loss of their flowers, which they lamented with howls and imprecations. Nothing was left to them but to gather more flowers and wait for the next train.

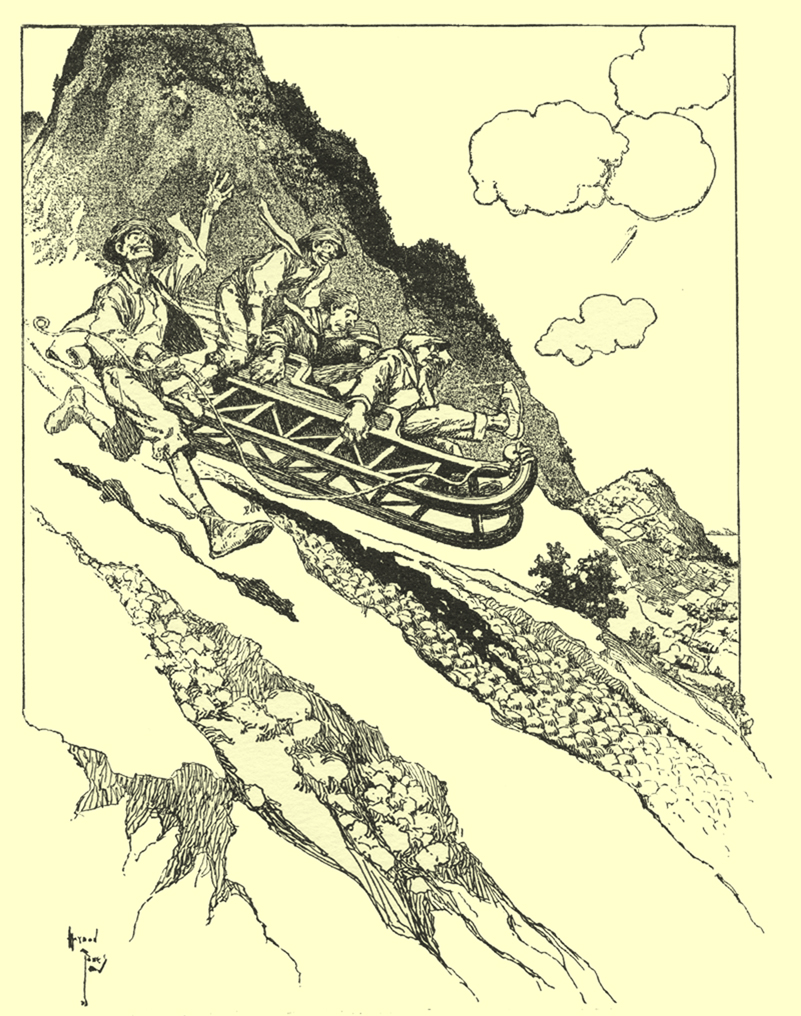

We had luncheon at the hotel on the mountain top, and on our return down the mountain some of the more daring ones took the sled road. One of these antediluvian sleds holds from two to four persons, and is manned by two natives who run, sometimes alongside, and sometimes, when room is lacking, atop the passengers and sled, shouting and screeching like Apache Indians. The downward path, which is paved with small cobblestones, is very narrow, very crooked, and in many places very steep; and if you can imagine a man or woman accomplishing the feat of riding a wild bare-backed buffalo four miles down a steep bluff though thick underbrush it will help you to understand some of the difficulties of clinging to one of these devil-machines flying down a rugged mountainside, with the passengers sometimes riding on top of the sled, but more frequently [ 9 ] with both the sled and its attendants on top of the passengers. If you survive the ordeal and reach the bottom you win; and all the sled-men expect of you for the fun they have had is that you buy them a bottle of wine — which I was more than glad to do in celebration of my lucky escape.

“IF YOU SURVIVE THE ORDEAL AND REACH THE BOTTOM, YOU WIN”

Our next stop was at Cadiz, whence we went inland to Seville. These places lie along the well-beaten paths of travellers and the experience of one visitor is usually common to that of all. In Seville, however, we met with an episode a little apart from the ordinary. My wife and I were assigned to the Hotel de Paris, said to be a very respectable hostelry. Our room was on the ground floor of what they called the annex, with windows opening on the main thoroughfare. The sidewalk was so narrow that by reaching out the window one could almost touch the passing vehicles on the street. The clatter of hoofs and honking of horns outside was so loud and constant and the noise and vibration so disturbing that even a deaf person could hardly have slept there. In our [ 10 ] haste and eagerness to get dinner and go to some native fandango we took no particular notice of these disquieting conditions, but on returning to our quarters shortly after midnight we took a more deliberate survey of the situation. The clatter and prattling in the street seemed to have increased rather than abated. It was a tremendous stone-floored room, large enough for a banquet hall, and cold enough for a cold storage room. There were two narrow iron beds, so far apart that between the noise outside and the great distance inside it would have been impossible to make oneself heard from one bed to the other without shouting. The air was stale and penetrating; and I discovered on turning back the covers that the sheets were as moist and chilly as if a pail of ice water had been sprinkled over them. Our teeth chattered, the goose-flesh stood out like pimples on our skin, and I could see pneumonia, malaria and all sorts of ailments in store for us if we undertook to spend the night in such a place. Since there was no prospect of either sleeping or resting there [ 11 ] in comfort, we gathered up our luggage, went to the office and demanded a better room. The clerk cheerfully informed us that there was not a room to be had in the town at any price, and that we were lucky to have a roof over our heads. Whereupon we paid our bill and took to the street in a drizzling rain, determined to seek shelter at the police station, if necessary. A few blocks down the street we found the Hotel Madrid, filled to overflowing, with twenty or more weary-looking travellers sleeping in chairs or on couches about the lobby. In answer to my inquiry for a room the clerk, after looking rather dubiously at our forlorn appearance, shrugged his shoulders, and waving his hand toward those reclining about the place, — “No hay lugar!” said he. “Yes,” said I, in broken Spanish, slipping an American ten dollar bill into his hand, “I understand that perfectly, but you must understand also that my wife, in her present delicate condition, can’t spend the night in the streets; so get busy and find us a warm room.”

[ 12 ]To my surprise, he answered in good American English, — “Oh, that’s different,” at the same time casting a sly glance at her healthy glowing features and slender figure, which belied my statement whichever way he might interpret it. “Wait!” he said as he made a hurried exit into the back office, where he doubtless examined the denomination of the bill. Presently he returned, smiling, and I could see the dimensions of the banknote plainly written in his eyes. He led us up one flight of stairs and into a magnificent steam-heated suite, all curtained and draped, with costly hangings, and a spacious marble-tiled bathroom adjoining. We slept so long and soundly that our sight-seeing party had nearly finished their rounds next day before we overtook them.

“I COULD SEE THE DIMENSIONS OF THE BANKNOTE PLAINLY WRITTEN IN HIS EYES”

A few days later we disembarked at Athens, where we spent a day viewing the ruins of the great Acropolis and motoring about the city and its environs. The most interesting feature about Athens is its imperishable memories. It suggests the Latin epigram, “Fame stays, but greatness goes.” [ 13 ] Five hundred years B.C., when Rome was comparatively an infant in arms, Athens was the recognized seat of culture, literary genius, and military power. It was from Greece that Rome received her education in matters of statecraft, copied her code of civic laws, derived her military tactics, upon all of which she rose to supreme power; so supreme indeed that she conquered Greece, stripped her of her independence and made her a subject province of the Roman Empire. But the ancient city of Athens now has little to commend it, other than the fact that in ages long past it earned an immense reputation, which has been widely commemorated in the literature of all nations. Its poets, philosophers, sculptors, statesmen and warriors exist only in history, and in its present state of inertia it reminded me of a wizened, decrepit old lady, enjoying the celebrity of having once been a famous beauty. Algiers and Constantinople, though less famous in classical literature, are far more entertaining. Indeed Algiers seemed to me one of the most picturesque cities in the world.

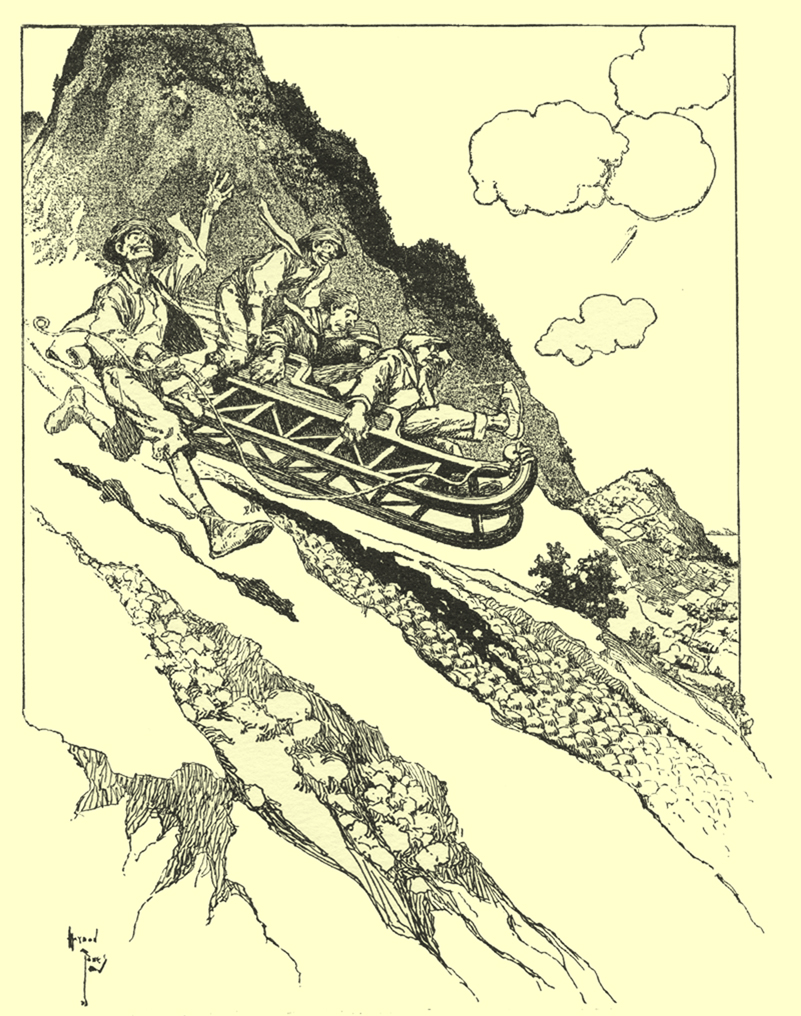

[ 14 ]Late in February we arrived at the hurricane-swept harbor of Haifa, where we debarked on small boats which bounced about on the choppy waves like kernels of popcorn on a hot griddle. We were now supposedly but a few hours from Jerusalem. “Jerusalem the Golden — with milk and honey blessed!” In song, yes; but in fact, with filth and vermin cursed! It was pitch dark, and raining, when we reached shore and boarded the train. Several hundred of us were crowded into open cars, outwardly resembling our cattle-cars — without heat, light or any comfort, and with but little protection against the wind-driven rain which beat in through the openings and soaked us to the skin. The conductor consoled us by saying that we should only have about six hours of this discomfort, but he proved to be a bad prophet, for when we were five hours out from Haifa our engine broke down on a steep grade, and there we sat in the cold wind and pouring rain for five hours more, until a freight engine came along and pushed us on up to Jerusalem, into which we made [ 15 ] a triumphal entry just before daybreak. At the station — some distance outside the walls — our party was bustled into a conglomerate assemblage of Ford cars and mule-drawn vehicles, and away we went, helter skelter for the city, amid a general uproar of shouting and babbling of the drivers in all sorts of languages. An uninformed by-stander might easily have imagined that we were a band of crusaders bent on taking Jerusalem by storm. A short distance out from the station our car, with three or four others, broke away into the lead of the scurrying, mud-slinging squadron, and on we sped over bumps and ditches, up a rocky road that seemed as if it would have taxed the ingenuity of a mountain goat even in daylight. Presently the headlights of our car went out, which served only to increase the driver’s speed, and we raced headlong through the dense blackness, expecting every second to be hurled over a precipice into eternity — perhaps face to face with the immortal individual who made Jerusalem famous. As we approached the towering walls of the city [ 16 ] some unregenerate rain-soaked wag in the back seat grumbled that he “wished to Christ he’d never heard of the place.”

“AWAY WE WENT, HELTER SKELTER, FOR THE CITY”

Finally in a half-scared-to-death condition we reached the hotel, which was crude, cold and dismal. However, it was reputed to be the best the city afforded. After considerable bartering I managed to get a room with a stove which resembled a large upright tomato can, with a long spindling stove-pipe, somewhat larger than a pipe-stem. We were supplied with a scant measure of wood consisting of small nuggets of the roots of olive trees, furnished at something like fifty cents a quart. But it was dry, and burned briskly; and in a few moments the tiny stove and about six feet of pipe were red hot. After being informed that the whole party was scheduled to be up an hour later to go “sight-seeing” we got to bed about six o’clock in the morning, tired and hungry, but still hopeful.

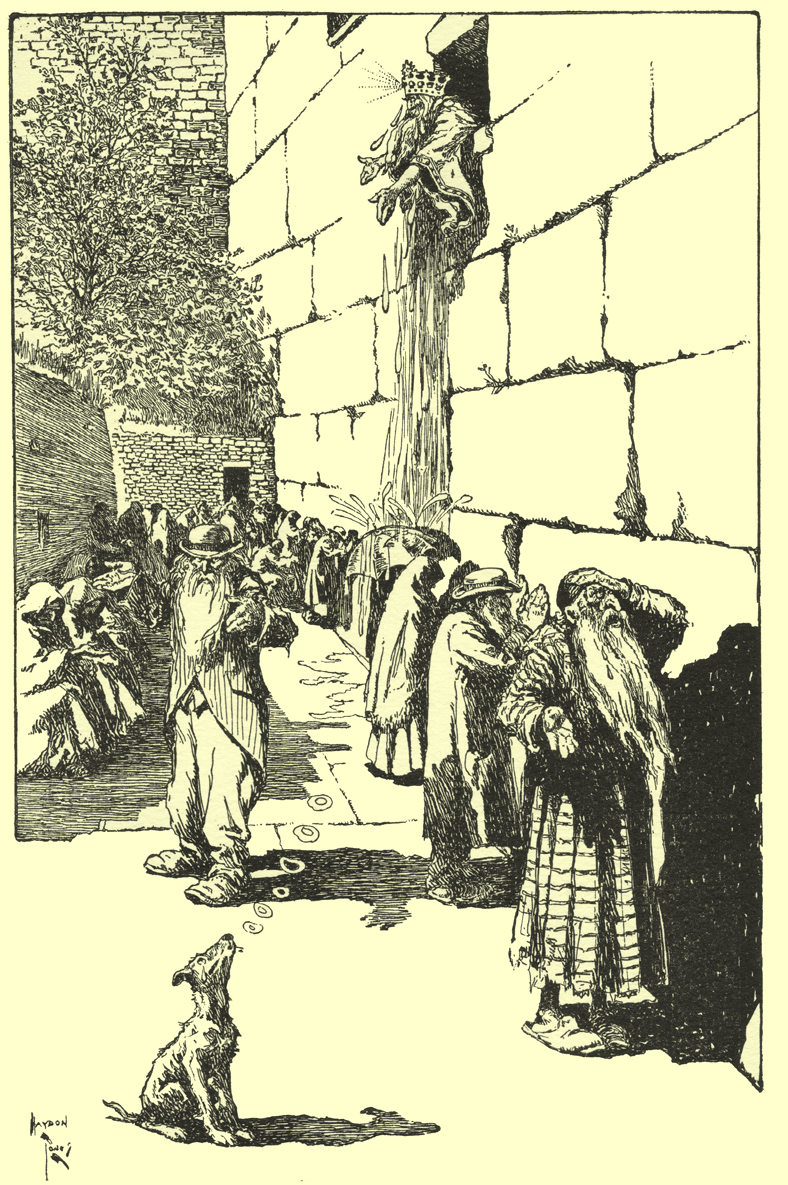

Jerusalem is one of those places which affords the reader vastly more comfort than it does the sight-seer. There were no vehicles in the narrow streets of the old part [ 17 ] of the city known as “Jerusalem within the Gates.” The thoroughfares are narrow, dingy, filthy, and crowded with a heterogeneous mass of donkeys, camels, goats, ragged dirty Syrians and Turks, sore-eyed children, blind beggars, cripples, paupers, and other nondescripts, all bustling about and rubbing shins and shoulders in one motley herd. The streets looked as if they hadn’t been cleaned since the crucifixion of Christ. There is no sanitation, the back streets and alleys serve the purposes of out-houses, and the whole place literally reeks with stench, flies, vermin, and all sorts of unsightly objects and unsanitary conditions. The vegetables in the market places were scrubby, withered and decayed, and the meat hanging in the open shops and stalls along the street was so covered with flies and fly-eggs that it was impossible to distinguish veal from red meat, or beef from sheep or goat meat. One member of our party told a story of a personal experience, which I don’t believe, though it could have happened, and he vouched for its truthfulness. He declared that on going [ 18 ] into a so-called “American Restaurant” he saw a blueberry pie on the counter, and that being his favorite pie, he said, “Give me a piece of that blueberry pie.” With a disdainful sniff and a swish of his towel over the dish, the attendant declared, — “Sh-sh! That ain’t blueberry — it’s custard.” Although Canton, China, owns the reputation of being one of the dirtiest cities on earth, Jerusalem is so unsanitary that they say a Chinaman can’t live there. If anyone doubts it let him attempt to thread his way through the littered alleyways leading down to what is known as the “Wailing Place,” which is indeed well named. It must be a stony-hearted individual who could visit this quarter without experiencing mingled feelings of sympathy and nausea — sympathy for the poor miserable looking wretches who rend the air with their woeful lamentations over the loss of Jerusalem, and nausea from the sickening sights all about. This place is contiguous to the ruined foundations of the Temple of Solomon, and if that wise old philosopher could look out of the [ 19 ] windows of his erstwhile magnificent temple upon the gruesome scene it is safe to say that he would drench the “wailers” with his burning tears.

“THE WAILING PLACE IN JERUSALEM”

One of the most singular things about Jerusalem is that scarcely any enterprising Jews are to be seen in or about the place. The better class of Jews are too thrifty a people to endure such poverty and uncleanness. To anyone who knows anything about Jerusalem it must be obvious that the current talk among civilized nations about turning it over to the Jews is nothing short of abject nonsense. You couldn’t keep an energetic American Jew there if you chained him to a monument. The place has no agricultural, industrial or mineral resources, and there is nothing about it that would appeal to the business, religious or patriotic instincts of the Jewish people. The mere suggestion of founding a home there for Jews (indigent Jews, presumably, since no others could be induced to stay there) raised a veritable storm of Moslem protest all over the world; and to consign a Jew to that unsympathetic [ 20 ] quarter would be to exile him from everything that is congenial to his tastes. In the past the Jews have been subjected to many insults and indignities, but I believe that nothing like Palestine has ever been put upon them.

The land in the vicinity of Jerusalem is so stony that in clearing it for gardening purposes the rocks are built into great mounds and high cross-walls, sometimes only six or eight feet apart, and a garden plot twenty feet square is a comparatively large field.

We drove out to the little town of Bethlehem, a few miles distant, and saw the place where Christ is said to have been born. The historic manger, or crèche, now forms a part of the basement of an old church. The low ceiling is hung with a great number of all sorts of lamps and lanterns which are kept burnished, trimmed and burning by the priests and other resident ecclesiastical representatives of various churches. We were told that the religious ardor and jealousy of these pious persons frequently manifests itself [ 21 ] in squabbling, and sometimes in sanguinary combats. It is a sad commentary on their devotional instincts that they cannot draw sufficient inspiration from the examples and teachings of Christ to enable them peacefully and reverently to restrain their animosities in the performance of their sacred duties in such an atmosphere. Although this is one of the principal places of interest, I was neither impressed with its sanctity nor convinced that Christ ever saw or touched the “sacred manger” or anything about the place. There are so many palpable fakes in the vicinity of Jerusalem, contrived solely to awe and befool the traveller, that one may be pardoned for entertaining some degree of skepticism. For instance, we visited the Mount of Olives, from which Christ is supposed to have ascended, and were shown a huge rock protruding slightly from the earth, with a small surface, a few feet square, inclosed with a low metal railing. In the center of this inclosure there is a small indentation in the stone, about as wide as the top of a teacup, and half as deep. The attendant [ 22 ] there points to this little depression, and with all the solemnity and impressiveness of pronouncing a judicial edict, he informs you that this is the heel print made by Christ when He was on the point of ascending into Heaven.

While such nonsense as this does not shake one’s faith in the former earthly existence of Christ, it tends to make one incredulous of the stories they tell about the exact place of his birth, his crucifixion and other details, all of which are as uncertain as some of the stories are ridiculous. We visited the Holy Sepulchre, over which a massive church now stands, and it is about the only place in all Jerusalem that impressed me with both its sanctity and its cleanliness. It is a small hallowed inclosure with a huge marble sarcophagus into which the Saviour is said to have been laid. Outside this sepulchre, a few feet distant, is a large smooth marble slab, called the anointing-stone, near which Mary is said to have knelt, and on which Christ was placed when taken down from the cross, nearby. It all seemed very touching, very [ 23 ] solemn, and more or less convincing, although it appeared to me a little strange that the body of Christ — who was ignominiously executed between two thieves — should have been interred in one of the most elaborate and costly tombs in all Jerusalem. Indeed it is claimed by many biblical students that He was neither crucified nor buried here, but at another place known as Golgotha, some distance away, and that His body was placed in what is now known as Gordon’s Tomb. There is about as much quibbling and uncertainty over these details as there is between different religious sects about the existence of the Holy Trinity; whereas they are all subordinate minutiæ having no bearing whatever upon our Christian duties or our ultimate salvation.

It seems both a pity and a shame, that the place of Christ’s nativity and habitation is permitted to become one of the most filthy, the most squalid, the most degenerate, the most unsightly, and the least habitable spots on the face of civilization. Billions of dollars are spent all over the world in erecting [ 24 ] and adorning great church edifices with steeples reaching far into heaven as monuments to Christ and His teachings, yet the locality where He was born and reared to manhood, where He preached the gospels that have filled the universe to its remotest corners, — in short, His birth-place, His home, His parish, and the scene of His execution and burial, — this holy, consecrated quarter has for more than five hundred years been suffered by all the Christian powers to remain in the hands of a sordid, unlettered, unwashed herd of mercenary heathens who have used its hallowed precincts as an advertisement or bait with which to attract travellers and curiosity-seekers, pretty much as a circus man would exhibit some monstrosity at a side-show. Having no belief in Christ, or decent respect for His memory, they have profaned many of its holy places with the most palpable and disgusting fabrications, and the place made sacred by the tears of agony shed by Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane is little more than a common romping place for unsanctified feet.

[ 25 ]Instead of indulging in useless talk about giving or selling Jerusalem to the Jews (who wouldn’t accept it as a gift if they had to live there), why doesn’t someone suggest that the Christian churches of the world unite in taking it over, cleaning it up and beautifying it in the name and memory of Him whom they worship? They teach us to keep our lamps trimmed and our houses in order for the second coming of Christ, yet no attention whatever is paid to putting His former earthly abiding place in a condition of decency and cleanliness. Its present state is a derision and disgrace to all Christendom. The birthplaces of authors are purchased through voluntary subscriptions of their admirers and preserved from destruction or desecration, while the home of the One who did more and suffered more for humanity than any other mortal who ever lived has long been neglected and abandoned to a tribe of philistines who, if they dared, would gladly cut the throat of every Christian believer. Were it possible to imagine that our Saviour could again be moved to tears it would be possible [ 26 ] also to imagine that to return and view His former home in its present condition would cause more grief than He was credited with before His crucifixion.

We spent three days at Jerusalem, during which time our chief articles of foot consisted of oranges, nuts, fresh dates and such things as could be pealed, washed or otherwise cleansed of the defiling touch of filthy hands. Although the climate in those parts is semi-tropical, the weather we experienced was cold, blustery and generally disagreeable. We wore heavy fur coats all the while we were there, and some even slept in them. In our party of several hundred persons there were many cases of pneumonia and other sicknesses, resulting from unwholesome food and exposure.

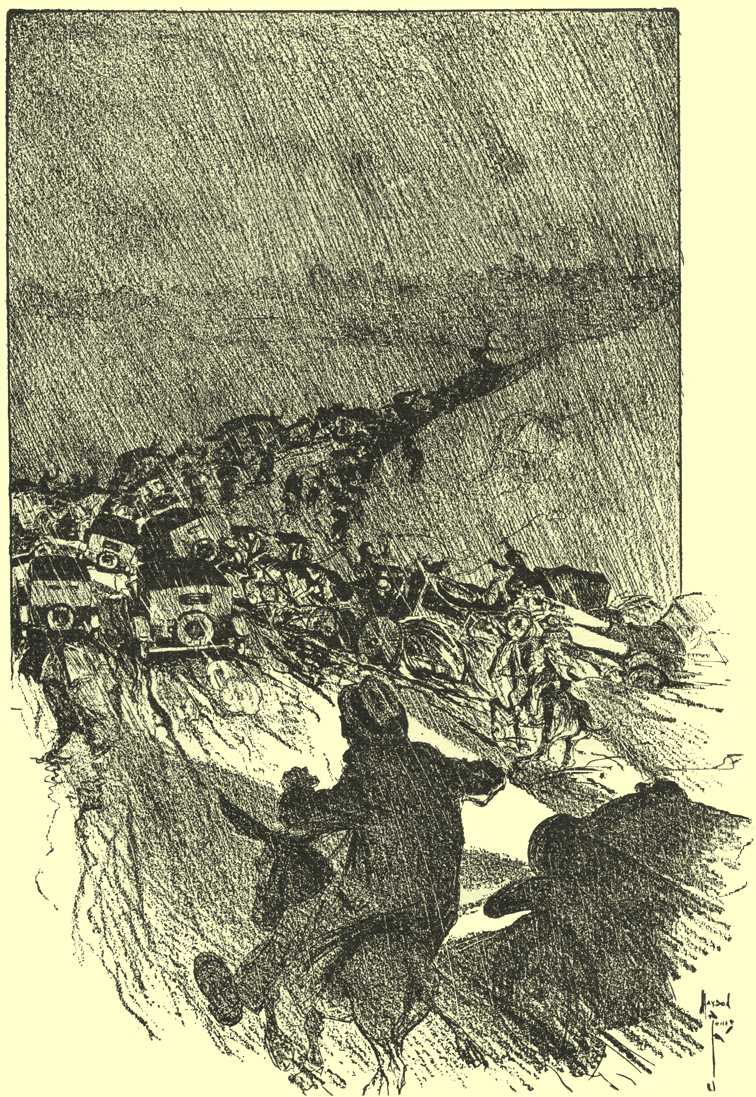

Our departure from the Holy Land was attended with even greater thrills of excitement than we experienced on entering it. Reaching Haifa late at night, several hundred of us embarked on an old flat-bottomed barge, without chairs or benches, to be towed out to the steamer, which lay at anchor a considerable [ 27 ] distance off shore. Before leaving our moorings the natives in charge conceived the idea of making a demand for backsheesh, which they proceeded to execute by taking up a collection; and immediately it became noised about that if we did not contribute liberally we were likely to be set adrift — not a promising outlook, in view of the blackness of the night and the high sea that was rolling in over the bar. The passengers not being in a generous mood, some of them resented this high-handed procedure; while others counselled submissiveness, considering that we were at the mercy of a band of heathens who would not hesitate to endanger the lives of the whole party. Although the mutterings among the tithe-gatherers indicated that the results of the collection were disappointing, after a considerable delay, attended by much shouting back and forth between the natives on the barge and those on the pier — the purport of which we could not understand — the ropes were cast off and we left the pier in tow of a tiny tug, which we could faintly hear, but could not [ 28 ] see. Half a mile or so out from shore a tremendous wave nearly inundated our barge and threw the passengers into great consternation, which was increased almost to panic on discovering that the hawser had been cut or broken and we were adrift in the open sea, with the wind blowing a gale from the shore! The man in charge of the party having remained at the station to meet the second section of the train, there was no one to give orders, and indeed no one to give orders to. We could see the lights of the ship in the distance, but the course in which we were drifting lay considerably to the right, which precluded any hope of coming within hailing distance. Matches were lighted and projected aloft, only to be instantly extinguished by the wind, and the roar of wind and waves prevented our voices from being heard any great distance. Meantime we were being jostled about on the flat surface of the tossing barge, with nothing to cling to, except one another, and in constant fear of being capsized. Some lusty-lunged individual who [ 29 ] was perhaps in great fear of being pushed overboard, invented the brilliant idea of commanding everybody to cast themselves flat on the floor, and this command was heeded by enough of those nearby to enable him, with several others, to scramble over their prostrate bodies into a place of greater safety.

If it be difficult for one sitting calmly on shore to conjecture what he would do in such an emergency, it will be readily understood how much more difficult it was under those circumstances to contemplate any means or prospect of escape. After an hour of wretched suspense — which seemed an age — the tug came alongside, and a little later we were all safely aboard the ship. It was highly amusing to hear the different versions of the adventure, and the various emotions it produced. Most of the narrators frankly admitted that they were frightened out of their wits, while one lion-hearted hero lyingly declared that his composure had not been in the least disturbed by the impending danger. I heard one [ 30 ] woman remark that she would surely have fainted but for the fact that she was in mortal fear of being washed overboard and drowned before she came to. Another good Christian soul declared that in the darkness of her despair she distinctly visualized her dear departed husband standing with outstretched arms to receive her, following which some remorseless cynic commented, — “Lucky for us that that tug came along when it did; we’d all have been in hell by this time.”

From Haifa we sailed to Alexandria, whence we had a comfortable train ride to Cairo, where we spent three weeks, more or less agreeably. Although Cairo and vicinity — particularly up the Nile — furnish scenes of great historic interest, we were so thoroughly fed up — with sight-seeing, not with food — that we contented ourselves with short trips to nearby places, with intermittent periods of rest and relaxation at the hotels.

haOne of the first requirements in Cairo, before attempting to see the sights, or even to go out on the streets, is to employ a stalwart [ 31 ] guide, armed with a heavy cane, to keep the other guides from pestering the life out of you. The moment you step out of the hotel you are confronted by a swarm of importunate boors who insist on accompanying you along the street, jabbering the while about places of extraordinary interest and importuning you to engage them. It is as impossible to shake them off as it is to get rid of a swarm of hungry mosquitoes, and your only defence is to hire one, not so much for guidance and information as for protection against the others; and the bigger and more ferocious looking he is, the less likely you are to be molested by other dragomen. The full name of our guide — whom we employed by the week — was Ramses Kuhfu Khafra Ratatf Menkaura Cheops Amenemhat Usurtesen Misphragmuthosis. Why his parents in naming him should have ignored the heads of other dynasties is more than I know. His commanding presence was no less formidable than his name. He did most of our bartering for us in the stores, and whenever a merchant asked a highly fictitious price [ 32 ] for any article — as they usually did — he had a way of bringing his cane down on the counter with a resounding rap that resulted in lowering the price from twenty-five to fifty per cent. We were told that it is customary for the shop-keepers to share with the guides the excessive profits on sales to customers they bring in; but this fellow prided himself on having done twenty years service as a guide without ever having accepted a gratuity from anyone other than those who employed him, — in support of which contention he carried a large bundle of recommendatory letters, — many of them by persons of distinction.

We climbed the Pyramids, rode the camels, camped two or three moonlit nights far out on the great sandy desert, got our eyes, ears and hair filled with sand, and did about everything else we could find to do — all of which nearly wore me out and made me wish I were back home where I could get some wholesome American-cooked food and a comfortable bed. The only diseases I contracted in Cairo were Egyptian sore eyes, malaria and [ 33 ] Egyptian “tummy;” but the Doctor assured me that if I remained until hot weather there were a few other malefic disorders that I could safely count upon.

But of all the privations, discomforts, pains and exposures of the entire journey the vengeful gods held their choicest malediction in store for us at Naples. We had heard inspiring stories about the world-famed Amalfi drive, which of course was on our itinerarium. The trip was by auto, through Pompeii and Sorrento. We started in the morning — a great train of a hundred or more automobiles — out along a cobblestone street in Naples, which was full of great holes and crevices, arranged at convenient distances so that just as the rear wheels pulled out of one hole the front wheels plunged into another. The cars were strung out in a long procession as far down the street as we could see, and the heads of the occupants bobbing up and down in the line ahead as the vehicles jogged into one cavity after another reminded one of a great row of jumping jacks doing an exhibition dance. [ 34 ] We had gone but a short distance when our rear springs snapped, letting the body of our car down flat on the axle, but an incident of such trifling importance was not destined to put us out of the race. After what seemed endless miles of this nerve-racking road our caravan emerged into a narrow dirt road on which the dust lay at least four inches deep, and was stirred up in such a continuous and blinding fog by the cars ahead that we could get only an occasional glimpse of the next car twenty or thirty feet in advance. We were whisked along through this suffocating cloud for upwards of two hours, during most of which time — having pounded the cushions flat on the hard seats — we assumed a half-standing, half-sitting posture; in other words, about the posture of one trying to walk with his fingers touching the ground, without bending his body. Several times while poised in this awkward, uncomfortable attitude the car striking an obstruction or a ditch bounced the loose seat up behind us with such force that we narrowly escaped being knocked bodily out into the [ 35 ] road. One of the women on — or rather suspended above — the rear seat declared that although she had given birth to six children, two of which were forceps cases and one a Cæsarian, in addition to having undergone three major operations for appendicitis, gall stones and a fractured hip, she never suffered so much agony altogether as she endured on this single pleasure jaunt. When we slowed down at Sorrento, which lies across the bay from Naples, my wife looked back from the front seat — the first time she had turned about for nearly two hours — and perceiving my dust-covered eyebrows and hair she threw up her arms in horror — “Good heavens! you’ve all turned gray!” she exclaimed. We stopped for rest and luncheon at Sorrento, and I had great difficulty, first in getting the dust out of my eyes, ears, nose and mouth, then in adjusting myself comfortably at the table; but since I should have been highly conspicuous eating in a standing position I managed finally to sit down, though very gingerly.

I decided to abandon the trip and return [ 36 ] to Naples by boat across the bay, but the water was unusually rough that day, and observing that most of the passengers in the boat just landing had to be carried ashore on stretchers we concluded it was safer to stick to the land. This far we had gone without coming to the real beauties of the Amalfi drive, which lay still in the distance ahead, and it was urged they ought not to be missed on any consideration short of death. So after luncheon we fell into line and sped away over the bumpy road at the usual forty-mile clip, with our rear bobbing in the air like the tail of a frantic kite. Sorrento is reputed to be a surpassingly beautiful place, and no doubt it is; but I was in no mood to become enamored with its charms.

The Amalfi road is one of the great engineering feats in the world’s history of road building. But another feat equally difficult is to ride over it at a break-neck speed without getting your neck broken. It runs for many miles along a tortuous, mountainous shore, with the ocean sometimes hundreds of feet below, and the great towering [ 37 ] jagged cliffs hanging over from above. But your admiration of the grandeur of the scenery is entirely subordinate to the anxiety you feel for your personal safety. Your time is about equally divided between wondering if at the next turn you are to be plunged over the precipice into the ocean, or if the towering rocks from above are going to tumble down and crush you in your tracks. Several disastrous avalanches have occurred in recent years. The drivers did not slacken their speed for curves, hills, rocks in the roadway, or any other hindrance. Like one hurrying to get away from some impending danger, they seemed to feel that the greater the speed the greater the safety; and they go pell-mell around curves so abrupt that the rear wheels throw the stones and gravel in showers clattering down the mountainside into the water below. In rounding one of the many sharp points you look ahead and feel sure you are going straight out over into the ocean, then a moment later with a quick gasp you look back and imagine the rear of the car is hanging over the cliff. [ 38 ] After pushing your hair back down on your head you set your teeth and wait for the next turn.

“DIZZYING SENSATIONS OF THE AMALFI DRIVE”

The objective point on this trip was the famous Capucini Monastery, where the sight-seers stop to refresh themselves and prepare for the return trip. This ancient institution stands far up the mountainside above the road, and commands an expansive view of the ocean and adjacent country. When we reached the place we saw a number of people, some viewing the wonderful scenery, others climbing up and down the long stairway; but we were so tired, sore, dusty and disgusted after being battered over the rough roads that we didn’t even get out of the car, but turned about and faced the cheerless prospect of returning over the same road whence we came. The return trip, though not so speedy, was no less uncomfortable. We had gone but a mile or so when one of the rear tires blew out and since the only spare we carried was a blown-out relic of some former trip, we ran along on one rim for a short distance, when the uneven distribution [ 39 ] of weight sent the other hind tire off with a bang. You will never appreciate to the fullest measure the real joy of comfortable autoing until you have ridden for twenty miles, as we did, over a bumpy road without rear springs or tires. After jolting along for upwards of an hour we came in view of a railroad station and saw a passenger train approaching from another angle, about the same distance as we were from the station. In response to my inquiry the driver said it was the train for Naples — the last one that day. Prompted by a sudden impulse of desperation I reached forward and tucked a bill in between his fingers that clutched the wheel and told him I’d double it if he could speed up and beat the train to the station, — which was about two miles distant. Unfortunately I neglected to consider what tremendous dragging and bumping power there is in the engine of a fifty-horse-power Fiat car. Instantly he threw the throttle wide open and it actually seemed as if the front wheels lifted from the ground, like an aeroplane beginning its flight. But [ 40 ] of one fact I felt assured, — the rims of the rear wheels remained securely grounded most of the way. The sensations of those last two miles were an unforgettable tragedy. The one thing that sustained me through the painful ordeal was the recollection of a remark my dentist used to make when he was about to attack an exposed nerve, — “Now take a deep breath and hold tight. It may hurt, but not for long.” We beat the train by at least four lengths, and like an exhausted Marathon runner whose last spark of endurance is quickened to a glow by the sight of the goal, we managed somehow to muster strength enough to scramble onto the platform. Abandoning the driver and what was left of his car we clambered aboard the train and reached Naples about eight o’clock at night, after the wildest pleasure trip that ever I undertook. I have seen pictures of persons being dragged at the tails of wild horses, but never could realize precisely how the victims felt until I experienced the remarkable sensations of our Amalfi trip. The journey from Naples to Amalfi and return [ 41 ] requires two or more days for comfort.

From Naples we went to Rome by train, and spent two days viewing the historic ruins, the catacombs, and other places of interest. We visited the great St. Peter’s Church, inside of which is a massive statue of St. Peter himself. He looked natural and healthy enough, except that he was a trifle maimed, having sacrificed the better part of his big toe to the devotion of Christian worshippers who have kissed it so often and for so many years that they have worn it down to a mere stub.

One reads so much about Rome and its celebrated places that in viewing the scenes they seem almost commonplace; and since we encountered no experiences beyond those which fall to the lot of most travellers I could relate very little but what travellers and readers are already familiar with. I found the Italian cooking nothing to boast of. We had luncheon at the Café of the Cæsars, one of the best cafés in Rome, where I ordered a small roasted chicken, and after dismembering and eating the legs and wings [ 42 ] I cut it open to get out the dressing, and found that only a portion of the insides had been removed.

In Italy the children of the streets are not only numerous but they are inveterate beggars. And a numerous body of the grown-up natives of that country — as indeed of most foreign countries — have so long schooled themselves in the art of painlessly bleeding travellers that they have become highly proficient. The cab-drivers and the hotel-keepers are the most skilled practitioners of this art, while the shop-keepers are a close second. One becomes so annoyed with being constantly bled by these human leeches, who confront the newcomer at every turn, that it detracts considerably from the pleasures of the trip, which are none too abundant at best. For example, in Rome my wife and I had a large room at one of the best hotels, for which were charged the extortionate price of twenty dollars a day in gold, without meals, and when we got the bill there was, in connection with various extras, a charge of five dollars per day for heating, though [ 43 ] there wasn’t a particle of heat in the radiators during the time we were there. It might reasonably be assumed that the price of twenty dollars a day would include all the necessary charges for one’s sleeping quarters; but not so at all. It is merely the initial or basic sum; in other words a peg on which to hang the aggregation of extra items. It would be amusing were it not so exasperating, to see the number of “extras” they can think of. Then the bills are so plastered back and front, with different kinds of revenue stamps — all of which you have to pay for — that they look more like stamp collections than like hotel bills. We felt that we had paid our pro rata share of the National debt.

We had a provoking experience one evening in Naples with a cabman whom we had engaged to take us to the Hotel Excelsior, where we had an appointment to dine with some friends. The distance was less than a mile, and the fare should have been about ten lire (fifty cents). After driving about the city for half an hour or so he drew up in [ 44 ] front of a rowdyish-looking suburban saloon and demanded fifty lire for his pains. I protested that he had not taken us where we wanted to go; but all I could get out of him was an explosion of vehement jargon, accompanied by a performance of wild gesticulations. He knew enough English to say “fifty lire,” which he must have repeated at least fifty times; and I knew enough Italian expletives to make him understand that I had no good opinion of him; which, however, had not the effect of assuaging his ire or reducing his demand. At length our altercation attracted the attention of a passer-by who volunteered to act as interpreter. It turned out that the fellow claimed he was a union cab-driver, and since there was a strike on, he did not dare take any passengers to the Excelsior. So he had merely taken us for a ride. The interpreter told us that in view of the bad locality in which he had landed us the cheapest way out of the difficulty was to pay his charge and get rid of him, which we did.

Writers tell perfervid stories about the [ 45 ] cultured people and the delightful sunny climate of Italy. I neither saw, felt nor heard anything that impressed me with the comforts of that country. On the contrary, we went from Rome to Naples in a driving snowstorm on the 23rd day of March, and nearly perished of cold and hunger. Someone — whether a wit or a philosopher, I know not — has said, “See Naples, and then die.” But it is not clear to me why anyone should wish to see Naples first, unless it be to make death seem less terrible. Certainly I saw nothing about the place that made me feel as if I wanted to die before getting away from there. Dramatic reviewers sometimes recommend tragical, tear-compelling plays to their readers; others advise a trip to Italy. But one does not need to travel far in foreign countries to discover that most of the objects, localities and conditions assume a less radiant hue than that in which they are usually depicted by enthusiastic literary artists. John Fiske, the American historian, wrote home from Naples in 1874: “Almost every man you meet looks as if he would love to [ 46 ] knock you down and take your watch, if he only dared to. Not only cabmen, but the hotel-keepers try to cheat you, most unblushingly. They are all thieves and liars, — the most dirty, cowardly, nasty, loathsome human devils I have ever seen, — especially here in Naples. . . . What can be done with such people! They have neither honesty nor ambition nor self-respect.”

From Naples we sailed to Villefranche, a port of entry near Monte Carlo, and spent the first two weeks of April at the Hotel de Paris in a large sunny room with wide balcony overlooking the Casino (or gambling rooms); also commanding a spacious view of the Mediterranean, and of the enchanting flower gardens in front of the Casino. In April and May Monte Carlo is indisputably the garden spot of the world, and the Hotel de Paris is also one of the best hotels in the world. Nowhere else have I ever seen such perfect room-service; and the charges were quite reasonable.

We reached Paris late in April. I imagine there must be times when it doesn’t rain in [ 46 ] Paris; but I never happened to be there on one of those occasions. Paris, however, has a contagious atmosphere all its own — a sort of vaccine vapor with which most visitors become inoculated by inhalation, producing a mild form of hypnosis under which they (women especially) become the succulent prey of artful manteau-makers and other money-collectors. In fact everybody, and everything, is artful in Paris; it is the centre for all kinds of art, — most of them rather costly to those who are artless. Yet withal, there is a tantalizing witchery about the place, — an indescribable something that lures and beguiles like the resistless wiles of a fascinating woman.

If the late war did not change Paris, at least it changed the attitude of certain classes of Parisians toward Americans, — upon whom many of them depend to a large extent for their livelihood. A cabman used to salute a customer who feed him half a franc, while now he feels at liberty to insult you if you fee him less than twenty-five per cent. of the fare. We were charged an arbitrary [ 47 ] fare of forty francs ($4.00 at that time) by a cabman who took us out to the races, whereas the fare indicated on the taxi-meter was precisely six and one half francs. The fact that the racetrack is a short distance outside the city limits leaves the question of price to the sole discretion of the cabmen, who are not famed for their tender conscience. Coming back, the asking price was fifty francs, the cabmen evidently figuring you must return, whatever the cost. My wife inquired of a cabman at the track what his return charge would be, and his prompt reply was, sixty francs. There followed some conversation, which I did not understand. We finally hired another cabman at a somewhat reduced figure, and when we were well on our way my wife said she told the first man that his price was too high; to which he insolently replied, — “All right then, you can Walk!” Under such circumstances perhaps it is just as well for a man not to understand their language. In Paris all visiting Americans are regarded as millionaires, and extortion from this class seems [ 49 ] to be a virtue rather than a crime. In some of the shops we discovered that the asking price for many articles was higher than the figure at which the same identical models could be bought for in New York, duty paid. There seems to be a general feeling in Europe that all Americans are profiteers; that they have corralled all the money in the world, and that they ought to throw it away liberally, or else stay at home. It is rather interesting to compare their present attitude with the loud acclamations with which they hailed the arrival of the boys in khaki during the darkest period of the late war. To discourse further upon Paris would be to waste time reiterating what hundreds of novelists, newspaper writers and travellers have said for the past fifty years or more. While there we drove out to the ill-fated city of Rheims, thence out along the battle front and the Hindenburg Line. The lines of towering trees along the sides of the road furnish one of the many sad testimonials of the war’s ravages. Many of these beautiful landmarks were shot [ 50 ] down and nearly all of them were more or less bereft of their branches, reminding me of two rows of great skeletons standing there like silent sentinels that had been blasted and petrified in their tracks by a devastating avalanche of fire and poison gas from the heavens. They looked out upon a landscape which had once been fertile, and bedecked with comfortable homes, orchards, vineyards and green fields, but now reduced to heaps of ruins and devastation, well-nigh exceeding the bounds of human imagination. Such fruit trees, shrubbery, vines and shade trees as survived the rain of shot and shell had been wantonly chopped down, and the dwellings, out-buildings and every vestige of structural form had been razed to the ground as effectually as if the devil’s hoof had been planted upon it. Buildings of brick or stone construction were torn down or blown to atoms, and those of wooden material were put to the torch. Not even a pig-sty was allowed to remain standing. Dead bodies and the carcasses of animals were flung into the wells, the fowls and domestic animals [ 51 ] were all destroyed, and every fragment of human sustenance was burned, demolished, polluted, or carried off, with the evident purpose of making the country uninhabitable for both the present and the future. Moreover, this fiendish work was extended to the gardens and the fields, which were churned into mounds and great cavities by exploding shells, so that the whole landscape has to be leveled, fertilized and remade. Towns and villages were obliterated, then undermined and blown up by explosives so that neither the owners nor their survivors could locate their building sites, or even the streets. We saw where one prosperous village had been so demolished that it resembled an old abandoned quarry, with great yawning chasms from twenty to thirty feet deep. These scenes recall the historic depredations of the Babylonians in Juda, and the cruel spirits of those invaders seem to have been reincarnated in the ones who engineered these hellish performances. The inhabitants of town and country had all fled or perished, the voices of the birds had been hushed, a solemn [ 52 ] stillness pervaded the air, and the sun shone upon a scene of desolation which suggested that the prophecy of the destruction of all living things by raining fire had indeed been fulfilled, and the devil with all his myriads of imps had overrun the country in a drunken soirée.

Here and there along the roadway were vast areas thickly studded with little wooden crosses which tell their silent, sad and lonesome story to the passer-by. On the outer edge of one of these sequestered cemeteries we observed the kneeling figure of a lone woman clinging to one of the crosses, with uplifted face.

Returning to Rheims we were even more impressed with the horrible realities of the deeds of barbarism. The once beautiful and well to do city where a hundred and twenty thousand souls had dwelt, presented an almost exact replica of Pompeii. The stores, homes and public buildings were shot to pieces and burned down, and miles of hitherto picturesque streets were churned up and strewn with wreckage, as if there had been [ 53 ] a general upheaval of the earth. The avenues of commerce were lined on both sides with gaping basements partly filled with ashes and débris, and in the saddened, careworn countenances of the few survivors one could read the melancholy reflection of the awful surroundings. If these scenes strike terror to the heart of one viewing them after peace and quiet have been restored, what must have been the feelings of those who witnessed their enactment! It seems incredible that a single human soul could have survived such an awful inferno.

We visited the great world-renowned Rheims Cathedral whose battered walls towered gloomily above this general ruin. For nearly four years this massive structure served as a special target for the German guns, and during that time an unbelievable number of tremendous shells were dropped through the roof and exploded within the walls, reducing the whole interior from pinnacle to basement to one vast cavern of destruction. During the bombardment the natives built a construction of logs and beams [ 54 ] extending far up the front in order to protect the multitude of saints, prophets and other immortals with which the whole façade is profusely adorned; but alas! These timbers caught fire and did far more damage to the figures than that wrought by the enemy’s shells. The features and limbs of these statues are burned and crumbled to a condition of unsightliness, and apparently beyond all human power of restoration. Photographs of the Cathedral taken since the war give but little idea of its real condition. We went inside and stood for a few moments gazing about in wonderment, at the barren walls and down into the great cavity below; but the structure was so perforated and shattered, and seemingly unsafe, that we hurried out and away at a safe distance, actually fearing that the towering ruin would tumble down on us.

My wife and I called on the aged Cardinal Luçon, who entertained us for nearly two hours with a narrative of his harrowing experiences while the war was in progress. He said that he had appealed repeatedly to the [ 55 ] Kaiser and to Hindenburg, both directly and through the Pope, to spare the Cathedral, but that a deaf ear was turned to all their entreaties, and at various periods for nearly four years the enemy’s fire was centered upon that one object. When the workmen engaged in sheathing up the front were spied by he German lookouts they became the target of a redoubled fusillade, and were shot down in great numbers, under the flimsy pretext that they had been sent up to spy on the German positions. The Cardinal told us that the city of Rheims was reduced from 120,000 inhabitants to a scattering twelve or fifteen thousand, most of whom burrowed in under the earth and existed in sub-cellars; and that vast numbers of these non-combatants — especially women and children — perished of starvation, and of disease resulting from polluted water and inadequate nourishment. The rain of shells was so unremitting that oftentimes the bodies, instead of being carried to the cemetery, were buried in graves dug in the dirt floors of the caves where they died. In one of these dugouts a [ 56 ] family consisting of a nine-months-old baby and five little brothers and sisters were found starving, the mother having been killed in the street while out searching for food.

The Cardinal said that the accuracy of the German fire was such that they could discharge the huge shells high in the air, and drop them with unerring precision through the Cathedral roof, and among the many howitzers that fired at random over the city there seemed to be one or two of the largest which were constantly trained on that one spot. With his own eyes he had seen literally hundreds of shells crash into the Cathedral, expecting with each explosion to see the walls collapse. Apparently nothing short of Divine Providence enabled the outer walls of this sacred edifice to withstand such a continuous, prolonged and destructive onslaught. He told us that the shots were fired mostly at regular intervals, and he could generally tell within a few seconds of when the next one would land. It is authoritatively said of this venerable prelate that in the midst of raining shells he could daily be seen standing [ 57 ] out in the open with bared head and uplifted arms supplicating heaven for the protection of his people and the restoration of peace; and that he made his diurnal rounds among the hovels and caves of the terror-stricken population, administering such comfort and sustenance as lay within his power and means. In his conduct he set an example of bravery, self-sacrifice and devotion which, though not widely advertised, should not be ignored by historians.

We were told that Verdun and other localities suffered even worse than Rheims and its vicinity, but what we had already seen was so depressing that we concluded to venture no farther. In Paris we talked with many natives, mostly authors and newspapermen, and found that almost without exception they were in a state of grave apprehension. It seemed to be the consensus of opinion that Germany had not been sufficiently chastened or subdued; that far from being repentant she was bent on more revenge, and that already she was secretly preparing a great air fleet with the purpose of annihilating [ 58 ] Paris and recovering Alsace and Lorraine within the next ten years.

After a three months’ trip made up of pleasures, privations and observations we returned home, better satisfied than ever with the land of our nativity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~