From Farm Spies, How the Boys Investigated Field Crop Insects by A. F. Conradi, and W. A. Thomas; New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916; pp. 56-78.

THE BLACK CORN-WEEVIL

THE town of Flanders and the country around it has always been known for its good people. Old Uncle Jerry Miller was born and reared just one mile east of town many, many years ago on his father’s farm, and he has lived and farmed on the old place all his life. Uncle Jerry knows everybody in town and every farmer in the country around it, and all the people know him. It was he who said, “There is no finer country than that around Flanders. It is level and the soil does not wash away as it does on the hillsides. I would not live in a hilly country anyway, because it seems to me that people must be wearing themselves out walking up the hills and then down again. We have good churches, fine schools, and first-class people. Everybody says so. The people here have a lot of sense, too. Talk about farming, our people have always known better than to raise nothing but cotton and wear the land out. Our farmers raise corn, oats, and hay; and there is not a home near or in Flanders that hasn’t a family garden. The farmers plow intelligently and they are always ready to learn; they are not the kind who think they know it all.”

57Uncle Jerry spoke the truth when he said that the people planted other things than cotton. They always made good corn-crops and were proud of it. They always made as good corn-crops as were made anywhere, but they could not keep the corn because an army of black weevils had come into their cornfields from somewhere and caused much loss to the golden ears. The habits of these little pests were so different from any they had ever found it necessary to fight, that the farmers did not know what to do. In the fields, as well as in the cribs, these little rogues would stay in hiding under the shucks like so many bandits in ambush. Unseen, every soldier of this black weevil army was busily eating into the kernels of the corn, and the farmers felt very bad about it. Every day you would hear some one say, “If somebody does not find some way of stopping these little black thieves, then all our corn will be eaten in the crib.”

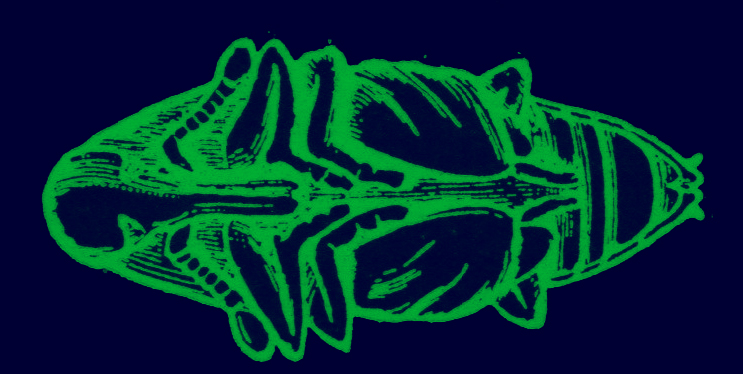

( After Chittenden, Bur. Ent., U. S. Dept. Agr. )

Fig. 31. — “Soldier of the black weevil army.”

“In the crib!” exclaimed John Matthews, who was one of the best farmers of Flanders; “it is not in the crib alone that they do so much damage, but I know when I gathered my corn in my river bottoms last month they had eaten into some of 58 the kernels on nearly every ear, and some ears were not worth hauling into the crib.”

( After Smith, N. C. Exp. Sta. )

Fig. 32. — “And some ears were not worth hauling into the crib.”

“Shucks,” said Fred Hamilton, “I never saw them in the corn in the field; you must be mistaken, John.”

“Mistaken?” answered John; “it seems that you do not know what you are talking about, Fred. They were in every field of corn I examined a couple of weeks ago before any of the corn of this section was put into the cribs.”

“It seems to me that I do remember having heard some people say that the weevils were eating their corn in the field,” said Fred.

“You must have,” said John, “because everybody has been talking about it.” And so they agreed that 59 this pest was becoming more destructive every year and that it was necessary to have something done to save the corn.

Joe Henderson, the bank president, had listened to these complaints about the weevils. Mr. Henderson was a successful banker and farmer; he was more than that, for he was a fine business man who was big enough to have the interest of his community at heart. Everybody knew this, and whenever he spoke, the people listened. One day they had a meeting to discuss ways for getting rid of the weevils.

Mr. Henderson said, “Gentlemen, corn is a great crop and must be saved. Every other crop must be saved, and the business men of Flanders will help you. This is a farming section, and the success of this town and its business men depends on the crops made by the farmers of the surrounding country. Without the backing of the farms this town could not be here, and now the people of this town must help the farmers to find some way of getting rid of this pest. The step for us to take right now is to get an entomologist down here to study this black weevil, and maybe he can find out how to kill the thief.”

“An entomologist?” asked Bob Griggs. “What is that?”

“It treats of the structure of words, Bob,” exclaimed Ben Gray, anxious to show what he knew.

Several who knew better laughed outright, and 60 this made Ben very angry. “What are you laughing at?” he retorted, turning red in the face. “The dictionary says that it is the derivation of words; I looked it up — now laugh, will you?”

This had the effect of making them laugh louder, which, in turn, made Ben’s face turn redder.

Mr. Henderson relieved Ben when he said, “You are thinking of etymologist; I said entomologist, which is taken from the Greek entom, meaning insect, and logos, a study. An entomologist is one who studies insects.”

“I never knew that there were men who made it a business to study insects,” said Bob Griggs.

“Yes, sir, they are called entomologists,” Mr. Henderson replied.

Soon after this meeting an entomologist arrived at Flanders who worked like a trained spy among the black bandits. The weevils were at work everywhere, on the low wet bottom-fields, on uplands, in near-by woods, but the entomologist was there also, and it was a common sight to see him crawling out of a crib with corn silk over his face and clothing. After he had worked a long time and had studied the habits and lives of the pests, he asked the farmers and business men to meet at the corn-crib on Jack Smith’s place on the following Saturday morning at ten o’clock sharp, when he would tell them what he had found out about the weevils.

[61]

Fig. 33. — “His big grove back of the barn was ‘chuck’ full of mules, wagons, automobiles, and people.”

62At the day and time set for the meeting the farmers came from far and near, over all kinds of roads, some on horseback, others on foot, and others came in big farm wagons. Some of the business men came in automobiles. Jack said that his big grove back of the barn was “chuck” full of mules, wagons, automobiles, and people. He said, “I am sure glad that my place is a little hilly, for if it were flat, there would not be room for them all.”

The entomologist came out of the crib and spoke to them: “This black weevil is by far the worst enemy the corn crop around here has to face. We have found out how these pests keep up their great numbers. The females bore little holes into the kernels, and into these they lay their eggs. One egg is laid in each hole, and the mother does everything she can so that no harm will come to the eggs or the little grubs that hatch from them.

Fig. 34. — “Into these they lay their eggs.”

The holes into which the eggs are laid the mother drills with her little beak, which looks like a tiny elephant’s trunk. The mouth being at the end of the beak makes it a very handy tool for digging. They make the hole as deep as the beak is long, and then the mother moves forward and puts into it her egg-guide 63 or sting and the egg is pushed down into the hole. The sides of the hole are not straight, as some of you may think, but the cavity has the shape of a hen’s egg with the larger end down in the kernel.”

Fig. 35. — “The sides of the hole are not straight, as some may think.”

“If the opening of the cavity is smaller than the cavity, how can the weevil put her egg into it? Either the eggs must be soft or the cavities are bigger than they need be,” Sam Sprague remarked.

“Both of your ideas are correct,” the entomologist answered. “The eggs are soft so that they can be squeezed through the opening, and they do not quite fill the cavity.”

“Ha, ha, she don’t make good fits, then, does she?” Sam laughed.

“Oh, yes she does,” the entomologist answered, “but she makes the cavities of that shape and size purposely, and I am sure it prevents the egg from being pushed out when the corn dries and shrinks. The eggs do not touch the walls of the cavity at all points, and this is of help to the little grubs when 64 working their way out of the eggshell at hatching time. When the egg has been pushed into place, the mother seals the opening of the cavity and that hides the egg and young grub from enemies that might be lurking about the corn.”

“You mean to say that the little white grubs you find in the corn are the young of the black weevils?” asked Sam Dixon.

“Most of the grubs you find around here are,” the entomologist replied, “but there are a number of white grubs in corn that do not make weevils. You can tell the weevil grubs without any trouble because they are white, hump-backed, and legless.

( After Smith, N. C. Exp. Sta. )

Fig. 36. — “They are white, humpbacked, and legless.”

The grubs eat the inside of the grain

![A black and white old photograph pf a corn kernel with a black porn-weevil [sic-copyright elfinspell.com 2009] grub inside.](../../images/Fig37-600dpiBW-PicG.jpg)

Fig. 37. — “The grubs east the inside of the grain.”

and when they become full grown they change to a quiet or resting-stage, called pupa, and from this pupa the full-grown weevil comes. In warm weather the time required from egg to full-grown insect is from five to seven weeks, but in cool weather a longer time is required.”

65

( After Hinds, Ala. Exp. Sta. )

Fig. 38. — “And from tjis pupa the full-grown weevil comes.”

“It puzzles me,” Sam Dixon interrupted, “how these little mischief-makers can eat the inside of the seed, and yet when I plant it most of the seed comes up. It would seem that they would kill the germ.”

“Yes, you bet,” Frank Hamilton added, “I have noticed that weevily seed will come up pretty well, but it does not make a stand of corn like sound seed.”

“That is what I say,” Bill Green spoke up. “I have found that out, and I will not plant any more corn that has weevils in it.”

“Very often the weevils will not hurt the germ,” said the entomologist, “but the gentlemen are right 66 when they say that weevily seed will not do as well as clean seed. The fleshy part of the seed is the young corn plant’s first food when it comes up, and when this is taken away the young plants will be weak and often die.

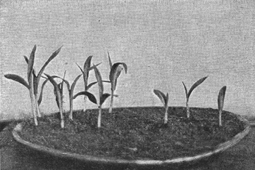

Fig. 39. — “Weevily seed will not do as well as clean seed.”

“It has been found that corn which ripens late is less damaged in the field than early corn,” the entomologist continued.

“That is a good point. I am going to plant late corn after this,” said Tom Jackson.

“Go easy, Mr. Jackson,” said the entomologist; “you are dealing with an army of bandits too wise to be easily fooled. If you planted late corn only, I am sure you would find the damage greater than we found it where both early and late corn occurred. We believe that the early corn could be used as a trap to attract the weevils when they appear in the field to lay their eggs. The early corn would be ready for them, while the late corn would not be. If there were no early corn, we are sure that this would not cause the weevils to starve. It might be well to plant late corn for your main crop and plant early corn for the weevils. Of course this trap corn should be gathered by itself and not stored in the same crib with the main crop.”

“Why not store it in the same crib?” George Sanders asked.

“If you stored it in your main crib, it would be 67 full of weevils by the time the main crop comes in. It would be just like saying to the weevils, ‘Here is some more corn, help yourselves.’ If they could, they would smile all over and say, ‘Mr. Sanders, you are a gentleman.’ You see you kept the weevils off your main crop by planting the early corn; now, would it be wise to gather the early crop, give the weevils a free ride to the crib, and then bring the rest of the corn to them to save them the trouble of flying to it? That would surely be treating the weevils kindly.”

“Ho, ho, ho,” many laughed.

“Put your thinking cap on, George,” several exclaimed.

The entomologist continued: “Select for your seed-corn such ears as give a good yield and have tight and close-fitting shucks. The ears should not stand up straight, but hang down to prevent water from entering the shucks during rains.”

Will Lane now interrupted the entomologist: “I have studied about that myself and always thought that the shucks had something to do with the number of weevils, but I met Sam Faulkner in town the other day and he said that he did not think much of it. He said he had an army of corn ear-worms in his corn last year and that the weevils got into the shucks through the holes made by these worms when they left the ears to go into the ground. 68 I always thought a heap of it, but then that is what Sam said.”

“It is quite true,” the entomologist continued; “the holes made by the corn ear-worms would offer a way for the weevils to get to the ears even when covered by tight-fitting shucks, but I have never seen a bad case of weevily corn in the field where the shucks were tight-fitting, and covered the ears, even where the corn ear-worms had made holes through the shucks. It is only in some years that this worm is very bad, and the holes they make do not offer as easy a way for the weevils to get in as the loose, short shucks. It may be that this Mr. Faulkner, of whom you speak, happened to look at a few of the worst ears, in which case it would not be fair to speak that way for the whole crop.

“Do not sweep your wagon beds near the crib after your corn has been unloaded. Many weevils are in that rubbish, and sweeping them on the ground near the crib would be helping them to get to the crib easier.”

Fig. 40. — “Sweeping them ont the ground near the crib would be helping them.”

George Brown interrupted the entomologist: “I am glad that I am here; what we have been told is of great value to us, but what are we going to do right now, gentlemen, when our corn is stored in the crib and the little six-legged thieves are making meal out of it? They are ruining my corn in the crib right now and I do not even dare to feet it to my mules.”

69“Oh, fudge,” exclaimed Fred Hamilton, “Tom Morrill gave me a simple remedy the other day and he said it worked fine. He tried it last year and he said his father always used it. He wets the corn with salt water when he puts it in the crib.”

“I tried it, and it works fine,” a voice was heard.

“I tried it, and it did not do any good whatever,” several gentlemen remarked.

The entomologist smiled and said, “You, who have tried it, seem to disagree.”

“What do you think about it?” several asked.

“We have tried it,” the entomologist answered, “and while the salted shucks seem to taste better 70 when eaten by stock, yet in our trials the loss was greater in the salted crib. Where salt or salt water was used it softened the corn in damp weather and the weevils seemed to like it better. There was even loss in weight.”

“Does heat kill the weevils? that is, could you haul the corn in wet or wet it after it is in the crib and let it heat to kill the pests?” one farmer asked.

“Where heat is under control it is no doubt the surest way for killing all kinds of stored grain insects, and in seed houses where steam coils are installed we recommend the use of heat. To obtain that heat by hauling corn in wet, we do not advise,” the entomologist answered.

“How much heat does it take to kill them?”

“The entire crib must be heated to a temperature of 123 degrees F. for several hours.”

“Does that injure the germ of the corn?” another asked.

“No, sir,” the entomologist answered. “The germ stands a much higher temperature for a much longer period without injury.”

“Don’t many of the weevils freeze to death in the winter?” Ed Green asked. “I have heard people say that the weevils cannot stand the cold weather.”

“I do not think that in our corn-cribs it ever gets cold enough to freeze many weevils. This may kill them farther north, where the winters are much 71 colder. During cold weather in the South the weevils became numb and quiet, and this has led many people to believe that the little rogues were dead.”

John Matthews said that most of the weevils are in the cribs during the winter and wished to know how they got to the fields. “Do they travel from the cribs to the cornfields?” he asked.

The entomologist told him that no breeding places had been found in the fields in the spring, and as the weevils leave the cribs when the corn is badly eaten, he thought that the pests traveled from the cribs to the fields. He also explained that breeding in the fields did not begin in earnest until the corn had begun to harden after the roasting-ear stage. He said further: “At this time the corn that may be still in the cribs is so badly weevil-eaten that in many cases the pests are forced to find something to eat; one will notice this during June and July, and during this time most of the weevils leave the crib. In the spring the weevils have been found in the fields eating other things, but the numbers found at that time could not very well account for the large number laying eggs in the fields when the corn hardens.”

“Let us come back to the question George Brown asked some time ago,” exclaimed Fred Hamilton. “Is there anything we can do right now to save 72 the corn that is in our cribs? After that we can talk about the things we should do next season to prevent the thieves riddling our corn on the stalks before it is put in the cribs.”

“Yes,” the entomologist said, “there is something you can do; go home and make your cribs just as tight as it is possible to make them. In brick cribs, or in wooden cribs that have been made very tight by the use of heavy tarred paper between two layers of sheathed boarding for the walls and ceilings, use about seven pounds of carbon bisulphide for every one thousand cubic feet of space. In cribs not so tight a much larger amount may be necessary.

“Carbon bisulphide is a liquid which looks like water and has a foul smell. When the liquid is exposed to the air it changes to gas very rapidly. This gas is heavier than air and sinks in the crib — it does not rise like most gases you know. It goes down, sideways, and eventually upwards. To fumigate with this gas, level off the surface of the corn in the crib and make holes by pulling out some ears. The holes should be about three feet apart each way and from one to one and one half feet deep. The liquid is then poured into the holes, using about an equal amount for each hole. The corn is then thrown back into the holes to help hold the gas, and the crib closed tight. Fire must be kept away from the liquid, and if any is left after 73 enough has been put in the crib, it should be kept in a cool place.”

“Is one treatment enough?” someone asked.

“Often it is if everything is just right when the liquid is put into the crib. Be sure and have the crib ready before you put the gas in. Some people forget and then have to open the crib every little while to fix something that should have been done before. One can soon find out if the first dose was not strong enough; if not, then a second and stronger one should be given. In most cribs it is best to give one dose in the fall as soon as the corn has been put in, and another in the spring. This should be done on warm days. The crib should be kept closed from twenty-four to forty-eight hours.”

“Can I go into the crib with a lighted lantern when the gas is in?”

“There is just a bare possibility of an explosion, and we would advise you not to carry fire of any kind near the crib at that time.”

“How do you air the crib when you want to open it again?” some one asked.

The entomologist answered, “Unless you have a brick crib, or a wooden crib very, very tight, it is not necessary to air it, because the gas will disappear in a day or two. In case of a tight crib, just open the door and the gas will soon disappear.”

“I tell you, gentlemen, this gas business looks 74 too dangerous to suit me,” said Orrin Doyle. “Were I to put that gas in my crib, then I could not go near the barn with a lantern, and what is worse, I could not even smoke my pipe near the crib, for fear of having my head blown off. I think I will let the bugs eat my corn and not take the risk of burning down my barn.”

“That is what I say,” added George Brown; “that plagued stuff will blow your head off. I believe I am scared of it.”

The entomologist answered, “You are evidently expecting your barn to burn down at any moment; at least, that is the way I would feel about my barn if I were in the habit of smoking in or near it. If you are used to smoking near the barn couldn’t you, for the sake of your crop, your family, and your stock, smoke elsewhere for a day?”

This caused an uproarious laughter, and the gentleman wished that he had not said what he did about smoking near the barn.

The entomologist then assured him there was no more danger than in the use of gasolene, so common in every home. He said further, “If you use the same care you would with gasolene, then you will not have any trouble. The liquid itself will not hurt the skin when it touches it, and the inhaling of a small amount of the gas would not injure any one.”

75“How about using it in a crib which has wet corn in it and the corn has heated?” a farmer asked. “Would it cause an explosion?”

“In a very tight crib I should be afraid to use it, but in most cribs there would be no danger,” was the entomologist’s reply.

A little man somewhere in the crowd exclaimed: “Bill Crane said that when he was in Fort Worth some of the big millers used this gas, and the people told him that they could taste it in the bread made from the flour of grain so fumigated.”

“I have known of such cases before,” the entomologist replied. “People know that it has a foul smell, but it is funny that they never taste it in bread when they don’t know the gas was used.”

“I have a newspaper clipping here where it speaks of two other things that have been tried for killing weevils. The names are terrible; I guess I won’t try to read them because it is after four o’clock now and I shouldn’t be able to get through pronouncing one of them before sundown,” and the farmer who said this came forward and handed the clipping to the entomologist.

“Both of these have been experimented with by the United States Department of Agriculture; the first1 one mentioned is rather expensive, but the second 2 seems to give promise. One point strongly 76 in their favor is that they do not burn like carbon bisulphide.”

So the meeting kept on, one question after another being asked by the farmers. They found out that Jim Blair had used this gas, and when asked about it he explained how he had used it. He told them that he had made his crib very tight and that he put the gas in on November 8. Mr. Blair said that he chose a warm, sunny day to put the gas in, and that he was very much pleased when he looked at his corn the next spring and found very few weevils in it. “Of course,” said he, “I would not come to a conclusion after just one trial, because it might have been a light weevil year, but I know of a half dozen other farmers who used it for several years with good results.

“Do not try to depend on treating corn in the crib to control weevils. The first step is to select your seed corn in the right way at harvest time. When selecting, look for type of plant, height of ear, yield, sound grain, tight shuck, and hanging ears.

Fig. 41. — “When selecting, look for type of plant, height of ear, yield, sound grain, tight shuck, and hanging ears.”

The tight shuck prevents the weevils from getting to the grain, but in most seasons the tip of the shuck will not be tight in ears that stand up because the soaking of the silk during rainy weather followed by drying in hot weather makes it so that weevils can get to the grain. Take pains to harvest your corn dry and put it in good cribs. Then if you 77 find it is necessary to fumigate, find out the best thing by writing to the experiment station or by asking the farm demonstration agent. There are so many things tried at present that we may soon have something that will take the place of carbon bisulphide.”

“Gentlemen,” said John Matthews, “it is getting late, and most of the people have to go home. I am going home to tighten my crib. I am going to select my seed corn more carefully after this. I know that I can grow a crop of corn, and after this I am going to save it.”

“So am I,” a dozen or more voices were heard.

The meeting was over, and a little later you could see men, women, children, teams, and cars going in almost every direction.

The people of Flanders have put these things into practice, and they have improved the corn of that community very much. Fred Hamilton said a few 78 weeks ago that he had always regarded the black weevil as a terrible pest, but that he had changed his mind, “Because,” he said, “that insect has done more to improve the corn around Flanders than anything else that ever came to this town.”

Joe Henderson is still president of the Bank of Flanders and one of the town’s best citizens. Everybody says that the best thing he ever did for that section was when he started the movement for having the black weevil studied which led to the long-remembered meeting at Jack Smith’s corn-crib.

Footnotes

1 Carbon tetrachloride.

2 Para dichlorobenzine.