From Farm Spies, How the Boys Investigated Field Crop Insects by A. F. Conradi, and W. A. Thomas; New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916; pp. 23-42.

THE BLACK BILL-BUG OF CORN

JOHN DRAKE had complained several times that something was injuring his corn, but was unable to find out what was causing it. One evening he came home with his face looking somewhat like a thunder cloud, and it did not require a second look for any one to conclude that he was in a very bad humor. His right hand was closed as if he was carrying something, and the children were wondering what he found that displeased him so. He walked to the dining room and laid two black beetles on the table.

Fig. 11. — “And laid two black beetles on the table.”

“I have caught them in the act,” he said. “These rascals are the cause of my corn’s dying. I found them in an old stalk, and you ought to see what they did to the inside of the stalk. They just about made sawdust ought of it,” and striking the table with his fist he looked at Mrs. Drake and the children about him.

24“They are not rascals; they are beetles,” said Johnny, who was too young to understand how his father felt. If Johnny had been old enough to be responsible for a corn crop, he might have understood.

“What??” Mr. Drake thundered.

Johnny in his innocence thought that he was asking for information, and so he repeated, “They are beetles. They have hard wing covers and ——”

“I don’t care what they are — they are killing my corn — they have killed it, and it made no difference to them what I said or did,” his father roared.

Johnny had by this time realized that he made a mistake when he spoke and that his father was in no frame of mind to listen to a story on insect structure. His father had discovered that these insects had killed his corn, and he wanted revenge.

“How are they injuring the corn?” Mrs. Drake asked.

“They are not doing any injury now because the corn is ready to gather, but what they did do is enough. I am going to get ready for war, and if necessary I will catch every one of them and twist their heads off. Yes, sir, that is what I will do,” he said, sitting with his chin in his hands and a grouchy look on his face.

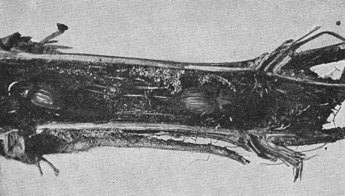

Fig. 12. — “But what they did do is enough.”

To the children it looked comical, and they would 25 have laughed had they considered it safe. No one laughed, you may be sure, or if he did he took good care that his father should not see him, because he was not in a humor to see anything funny about this.

Johnny had to go to school the rest of the week, and he saw farmers all around him harvesting corn. When he came from school the first evening after his father had found the beetles, he asked him whether he had found any more.

“No,” his father answered, “I cut dozens of stalks open to-day, but I did not find another beetle.”

So it was the rest of the week. His father had been cutting stalks but had found no more beetles. On Saturday morning all the corn had been gathered, and only the stubble were left in the fields. There was much other work to do at this time of the year, so that the beetles were soon forgotten. One very cold morning in January, as Johnny started to school, 26 he met Frank Welden on the road, and they walked along together. Mr. Welden was one of the oldest farmers of that neighborhood, and was very fond of Johnny.

“Well, Johnny, this is a cold morning, but when a man has plenty of good kindling-wood, plenty of meat, potatoes, and fruit in the cellar, and his barn full of fodder, he does not mind so much. That is what I like about farming; we farmers always get along better than many of the people living in town.” So Mr. Welden talked to Johnny and Johnny listened to every word he said. When they came to where they could see Mr. Drake’s cornfield on the right of the road, Mr. Welden said, “Johnny, tell your father that he should not be leaving the corn stubble on the field over there the way he does.”

“Why?” asked Johnny.

“It is a bad thing to do. It is only common farming. Those stubble somehow make lots of bugs next year,” Mr. Welden explained.

Fig. 13. — “Those stubble somehow make lots of bugs next year.”

Just at this time they came to the cross-road. “I will tell him what you said,” Johnny called as he left Mr. Welden.

When Johnny came home that evening he told his father what Mr. Welden had said.

Mr. Welden believes that all kinds of insects stay in those stubble during the winter,” his father replied.

27“Do you believe that?” asked Johnny.

“I don’t know whether I do or not. It looks to me as if any bugs trying to stay in those stubble would freeze to death during winter,” Mr. Drake replied.

“I have been thinking about it,” Johnny continued; “the little bugs have no houses with warm stoves and I have wondered many times what they do through the long cold winter when there is no food. I should certainly hate to be a bug.” At this remark by Johnny the whole family laughed.

“What makes you think that the bugs live during the winter?” asked his mother. “I thought they all died in the fall.”

28“My teacher told us that bugs lived during the winter in a quiet, sleepy condition called hibernation,” Johnny replied; “during the winter, she said that they did not have to have food, and that from the bugs that stay over winter the insects come the following year.”

“All right, Johnny,” said his father with a laugh, “I give you a job for next Saturday. You go over the old corn stubble in the field back of the barn, cut them open and examine them closely to find out if there are any bugs in them.

“I’ll do it,” answered Johnny. They all laughed, and no more was said about the subject that evening.

On Saturday morning, Mr. Drake, saw Johnny going across the field. “Where are you going, sonny?” he called.

“I am going to hunt for the bugs you told me about the other evening,” Johnny answered.

Mr. Drake, laughing with a “guffaw,” said, “Well, well, boy, go easy now and don’t catch them all, because if there happened to be no bugs next year it would surprise me so that I could hardly get down to business, and then the weeds would cover my cornfield.”

“That is the time I would plow the corn for you,” Johnny answered, laughing, and walked on.

When he arrived at the cornfield he confessed to himself that he had little faith in finding bugs in 29 the corn stubble, and if he failed the folks at home would laugh at him. Starting in a half-hearted way he selected the biggest stubble he could see and putting his right foot on one side and his left on the other he stooped over and begin pulling with both hand as hard as he could, — in fact he pulled so hard he grunted. While pulling he bit his tongue between his teeth and drew his fact out of shape as if he were suffering severe pain. When he had pulled, twisted, grunted, and looked painful for some time, the stubble, root and all, came so suddenly that Johnny was not prepared, and he fell backwards, almost turning a somersault, with earth flying over him. He remained on his back a few moments as if to catch his breath, then got up, stiffly, like an old man, and sat rubbing his eyes. He put his hands down, winked hard a few times, and then rubbed his eyes some more. He kept on spitting and sneezing, wondering if he would ever get rid of all the pieces of earth that had lodged in his eyes, nose, mouth, and ears. Then he slowly drew his knife from his pocket and split the stubble and root. What do you suppose he saw as he laid the two pieces on the ground very quickly and looked at them with bulging eyes? He thought that he saw three bill-bugs partly hidden in little nests in the dried and rotten pith of the inside of the stubble.

“I must have fallen pretty hard, for I never see 30 such things except when I dream at night. I wonder if the fall hurt my eyes.” He rubbed them once more, quite thoroughly this time. He looked again, and, sure enough, the bugs were still there. He broke a piece from another stubble, and getting down on his knees he pushed the beetles and turned them over.

Fig. 14. — “He looked again, and, sure enough, the bugs were still there.”

“My eyes are all right, and those are bill-bugs as sure as I live. I bet they are dead, or maybe asleep, — no, I saw that one move.” He pointed to one of the beetles which he saw move its legs. After a few moments he saw the others move slightly.

“Hm, they act like boys when you wake them up in the morning, except that they do not yawn. 31 Maybe they do, but their mouths are so small that I cannot see them. To tell the truth I do not know yet at which end the mouth is located.” So Johnny spoke to himself, at the same time carefully studying the beetles. He saw the eyes and feelers, and then was sure that the mouth was at the end of the little beak. Looking at them gravely, he said to himself: “They look like elephants except they are blacker, much smaller, have no tails, no lopping ears, — well, I guess they are not like elephants after all.

Fig. 15. — “They look like elephants, except — ”

Why should my looking at them have reminded me of elephants? Oh, I see now, those little beaks did it, because they remind one of elephants’ trunks. That is it. Well, well, well,” he sighed and looked about him. “I am going to pull some more, and I will surely take some home to show to father. See here, I did not come to practice for a circus, so the next stubble I am going to dig up, and then there will be no danger of my turning somersaults without knowing it until it is all over.” He went to a near-by fence, broke off a good sized sliver, and with it he dug up many more stubbles. With his knife he split these open. Finding beetles in most of them, he was no longer discouraged, but felt that he was being well repaid for his trip. It was a great relief that they could not laugh at him when he 32 returned home, because he had a discovery to report and the bill-bugs in the stubble to prove it.

Did you ever discover anything, and do you remember how good you felt about it? Here in these innocent-looking corn stubble was the winter home of the corn bill-bug. There the little insects slept throughout the long winter when the ground of the stubble-field was frozen and icicles hung from the eaves.

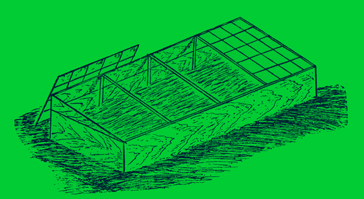

When he came home and showed them what he had found, they all became very much interested. “Johnny,” said his father, “that cold-frame back of the chicken-coop I give you for an insect-breeding cage. It is my cold-frame, but you clean the glass in sashes well, and then get more stubble from 33 the place where you got these and put them in the ground in the cold-frame just as they were in the field; do not cut the stubble. Please get the stubble to-day, because I am going to plow them up and remove them from the field. I’ll warrant that they will not stay there this winter to breed the bugs to eat the corn next summer. It begins to look to me as if I have been breeding bugs to eat my corn. No more of that; I am going to see the neighbors and tell them about this and ask them to destroy the stubble.”

Fig. 16. — “Johnny, the cold-frame back of the chicken-coop I give you for an insect breeding-cage.”

Johnny got the stubble as his father had directed, and put them in the ground under the glass sashes. Not a day passed that Johnny did not look into the cold frame. It took much tedious waiting through many weeks because the insects would not stir as long as the tang of frost was in the air. Johnny said he thought it was the longest winter he had ever spent. When at last the warm weather of spring set in, the insects woke from their long sleep and left their winter homes to find something to eat.

“I do not blame them,” said Johnny, “because such a long nap would make anybody hungry.”

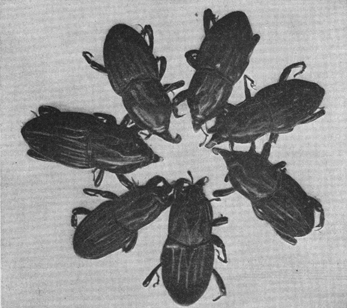

During the first few days they did not seem to be able to get their appetites in good condition even though Johnny had been so thoughtful and planted five hills of corn in the nice rich soil of the cold-frame. They wandered about as if uncertain what 34 would be the best thing to do. Sometime several beetles would gather near the same spot with their heads close together. One morning a funny thing happened; seven of the beetles had gathered near the same spot with heads near together. When Johnny saw them he laughed outright and called his father. Mr. Drake came, pulled his spectacles from his vest pocket, put them on his nose, and slowly and awkwardly set the bows over his ears, in the meantime drawing his face out of shape as though the putting on of spectacles was a painful piece of work. Johnny got impatient because he was afraid that the bugs would leave their positions before his father would get through putting his spectacles on.

“It does take dad a long to get ready before he can look at anything carefully,” he said to himself very impatiently.

Mr. Drake at last got his spectacles where he wanted them, and looked at the spot which Johnny pointed out to him.

“They must be plotting,” his father said in a low, careless voice, and putting his spectacles back in the vest pocket he walked to the barn, where he had some work to do.

Fig. 17. — “They must be plotting.”

Johnny’s eyes followed him, searching him from head to foot until he disappeared form sight through the barn door; then, turning around he spit on a chip with much emphasis and grumbled to himself: “I didn’t learn much, did I? 35 He seemed to be short about it. Maybe, though, he had had no opinion about it, and if that was the case he said enough.” He looked at the beetles again and they were still in the same position. “I must be getting ready for school,” he said, and left the insects to themselves.

The next day Johnny saw that they were beginning to feed, and he watched them as carefully as he could day by day. They attacked the tender little 36 cornstalks near the surface of the ground. With their beaks they would slit them and eat the juicy parts on the inside, which would soon kill the bud, leaving a few green leaves at the bottom of the stalk. There was not very much excitement in this for Johnny. “Because,” he said, “the beetles just kill the young corn and that ends it.” However, his curiosity had been aroused, and so he kept watching. It was well that he did, for later in the season he had a chance to see something that stirred his blood. He saw them attack the corn in a field where the plants were from ten to twenty inches high, and the way the plants battled for life was as good an example of perseverance and true courage as he had ever read about in his books. “And this is a living example right before my own eyes,” he said.

When the plants had become twisted and distorted from the hard attacks of the bill-bugs and growth seemed no longer possible, each plant threw out suckers near the ground as if to say, “If I must die, then maybe these young sprouts will succeed in making corn.”

( After Kelly, Bur. of Ent., U. S. Dept. Agr. )

Fig. 18. — “Each plant threw out suckers.”

Often these suckers were attacked, but being as brave as the old stalks from which they came they were determined not to give up the fight, but before they died produced a second set of suckers. In their heroic struggle for life the plants continued to produce suckers, until at last 37 the old dying plants were surrounded by a mass of sprouts that made the field look very odd. Many of the plants were so riddled by the repeated attacks of these pests that they could not succeed in making grain. Johnny sat down by one of these masses of suckers and examined it very closely. Looking at the dying shoots he shook his head gravely and said: “Old fellows, you have taught me a lesson that I will not forget as long as I live. You were true to the farmer who so carefully prepared the land and planted the seed from which you came. He hoped to make a crop, and that it cannot be done is no fault of yours. You fought bravely, but the enemy was stronger than you; you had to go down in the fight, but you went down fighting like heroes.”

Johnny found later that when the corn had grown to the height of four feet the beetles could no longer injure it seriously. He thought that the battle was over, and was greatly surprised afterwards when he found that he had seen only part of the fight.

38“Why, man,” he said to his little friend Willie Burns, “those beetles were but the skirmishers of the bill-bug army.”

He had forgotten about the eggs the beetles had been laying on the corn. He had noticed the egg-laying from June 1 to July 1. The eggs were laid in tiny holes which the mother beetles had made with their beaks, and they had laid anywhere from one to ten eggs in a stalk. One reason why he had paid no attention to this was because those stalks were not damaged like the others. He had just taken it for granted that these stalks would go through the season safe, but when he found that the eggs had hatched into little 39 whitish, humpbacked grubs eating the pith he felt that they had not only outwitted the corn but himself also, and this hurt him very much.

( After Kelly, Bur. of Ent., U. S. Dept. Agr. )

Fig. 19. — “The eggs were laid in tiny holes.”

The little grubs were gluttons, eating all the pith from that part of the stalk where they worked, leaving only the outer woody wall of the stalk.

( After Kelly, Bur. of Ent., U. S. Dept. Agr. )

Fig. 20. — “The eggs had hatched into little whitish, humpbacked grubs.”

This, of course, cut off the flow of sap and killed the plants. It was a dry season, and the attacks were so deadly that much of the corn was killed even after silking and tasselling.

“This beats everything,” said Johnny; “they played it on me this time, but I am going to watch them closely after this, and if they do succeed in ‘stealing another march on me,’ it will not be on account of my being asleep.”

Johnny did see their next move, but it was not until they had become full-grown grubs. They made little cells from chewed pith in the stalks and in them they changed to the quiet or pupa stage. Johnny had read about such things in his books, but this was the first time he had ever seen it.

( After Kelly, Bur. of Ent., U. S. Dept. Agr. )

Fig. 21. — “They changed to the quiet or pupa stage.”

From these pupæ the full-grown bill-bugs escaped. Few of them came out of the stalks, and as winter approached nine out of every ten beetles remained in the stalks just as Johnny had found their parents in the corn stubble last January.

40When Johnny told Mr. Welden what he had seen, the old man asked: “Where do they stay? I have never been able to find any.”

Johnny answered: “The beetles are unlike boys, because these little pests are early risers. They enjoy a good breakfast and supper, but during the hotter parts of the day they hide in the shade or just underneath the soil at the base of the plants.”

“That must be the reason that I never saw them; I looked at the wrong time of the day,” Mr. Welden replied. “But see here, sonny,” he continued; “it seems to me that when we move the stalks from the field after harvest we are taking the beetles with them; don’t you think so?”

“Right there is where the beetles get the best of us, because they do not stay in the stalks. I have cut hundreds of them open and never found a single insect, but if you will cut open the stubble or root, you will have no trouble finding them. When we carry our stalks away we must take stubbles and roots also,” Johnny explained.

Old Mr. Welden was now as tickled as a schoolboy who has had good luck. He had such a broad grin on his face that Johnny wondered how he could do it without hurting his face.

“Sonny,” he said, “do you remember when I told you to destroy your corn stubble? I have farmed all my life and I have noticed that where you leave 41 the stubble during the winter the bugs are worse on your corn the next year. I was not able to ‘ferret’ it out, but you see now that the old man was right. And I can tell you another thing, sonny; I never plant corn where I had corn the year before, and whenever I can do it I plant as far away as possible from where corn was before. You don’t believe that is important, do you?”

“I do, Mr. Welden,” Johnny replied; “you are one of the very best farmers of this section, and I 42 have seen you make crops when other the farmers failed. I like to hear you talk.”

“I always knew that you were a sensible boy,” said Mr. Welden; “and now let the old man tell you another thing. I have made crops when others failed because I had planted my corn just as early as it was safe from frost in March. You can’t always do it on account of the weather, but whenever I can do it the bill-bugs won’t get my corn as bad as that which is planted later.”

Fig. 22. — “I have made crops when others failed.”

“Is that so?” Johnny inquired.

“That is so, Johnny, and now I have to be going. You take what I told you and make your pa put it in his pipe and smoke it.” At this they both laughed heartily and parted.

“Mr. Welden is a good friend and he is a smart man, too,” Johnny mused as he was walking down the road. Suddenly he stopped as if he had forgotten something. “What about that early planting for bill-bugs? I bet I know. If you can get your corn to silking and tasselling before the beetles lay their eggs, the corn is then strong enough to win the battle.” He walked on some distance when he suddenly stopped again. “What did that speaker say at the farmers’ meeting last month? He said ‘the right planting date for bill-bugs often is food for bud-worms.’ What did he mean? Gosh! There is a lot to be learned yet about this bug business, but I bet I’ll know that too, some day.”