[Click on the footnote symbols and you will jump to the note on the bottom on the page. Then click on the symbol there and you will be magically transported back to where you were in the text.]

From Romantic Castles and Palaces, As Seen and Described by Famous Writers, edited and translated by Esther Singleton; New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1901; pp. 61-67.

[61]AN enclosure of large walls. My djin stop in front of a first gateway in the ancient severe and religious style: massive columns with bases of bronze; a narrow frieze sculptured with strange ornaments; and a heavy and enormous roof.

Then I walk into the vast deserted courtyards, planted with venerable trees, to the branches of which they have given props like crutches for old men. The immense buildings of the palace first appear to me in a kind of disorder wherein I can discern no plan of unity. Everywhere appear these high, monumental and heavy roofs, whose corners turn up in Chinese curves and bristle with black ornaments.

Not seeing anyone, I walk on at random.

Here is arrested absolutely the smile, inseparable from modern Japan. I have the impression of entering into the silence of an incomprehensible Past, into the dread splendour of a civilization, whose architecture, design, and æsthetic taste are to me strange and unknown.

A bonze guard who sees me, advances, and, making a bow, asks me for my name and passport.

It is satisfactory: he will take me himself to see the 62 entire palace on condition that I will take off my shoes and remove my hat. He brings me even velvet sandals which are offered to visitors. Thanks, I prefer to walk with bare feet like himself and we begin our silent walk through an interminable series of halls all lacquered in gold and decorated with a rare and exquisite strangeness.

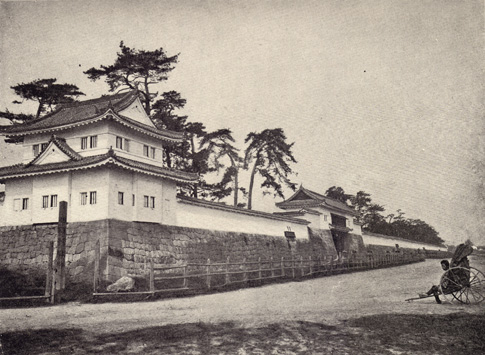

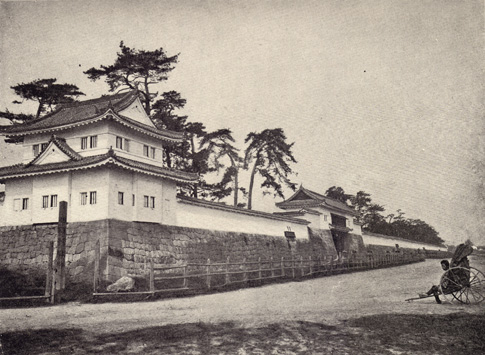

THE MIKADO’S PALACE, JAPAN.

On the floor there is always and everywhere that eternal spread of white matting, that one finds just as simple, as well kept, and as neat in the homes of the emperors, in the temples, and among the middle classes and the poor. No furniture anywhere, for this is something unknown in Japan, or slightly known at most; the palace is entirely empty. All the surprising magnificence is upon the walls and ceilings. The precious golden lacquer is displayed uniformly on all sides, and upon this background, Byzantine in effect, all the celebrated artists of the great Japanese century have painted inimitable objects. Each hall has been decorated by a different and illustrious painter, whose name the bonze cited to me with respect. In one there are all the known flowers; in another, all the birds of the air, and all the beasts of the earth; or perhaps hunting-scenes and combats, where you see warriors dressed in armour and terrifying helmets, on horseback pursuing monsters and chimæras. The most peculiar one, assuredly, is decorated entirely with fans, — fans of all forms and of all colours, open, shut, and half open, thrown with extreme grace upon the fine golden lacquer. The ceilings, also of golden lacquer are in compartments, painted with the same care and the same art. What is, perhaps, the most marvellous of 63 all, is that series of high pierced friezes that extends around all the ceilings; you think of generations of patient workmen who have worn themselves out in chiselling such delicate, almost transparent, things, in such thicknesses of wood: sometimes there are rosebushes, sometimes entanglements of wistaria, or sheaves of rice; elsewhere flights of storks that seem to cleave the air with great velocity, forming with their thousands of claws, extended necks, and feathers, a crowd so beautifully combined that it is alive and scurrying away, nothing lags behind, nor falls into confusion.

In this palace, which is windowless, it is dusky, — a half-darkness favourable to enchantments. The greater number of these halls receive a shimmering light from the outside verandas composed only of lacquered columns, to which they are entirely open on one side; it is the subdued light of deep sheds, or of markets. The more mysterious interior apartments open on the first by other similar columns, and receive from it a still more attenuated light; they can be shut at will by bamboo curtains of an extreme delicacy, whose tissue in its transparency imitates that of a wave, and which are raised to the ceiling by enormous tassels of red silk. Communication is had by species of doorways the forms of which are unusual and unexpected: sometimes they are perfect circles and sometimes they are more complicated figures, such as hexagons or stars. And all these secondary openings have frameworks of black lacquer which stand out with an elegant distinction upon the general background of the gold, and 64 which bear upon the corners ornaments of bronze marvellously chiselled by the metal-workers of the past.

The centuries have embellished this palace, veiling a little the glitter of the objects by blending all these harmonies of gold in a kind of very gentle shadow; in its silence and solitude one might call it the enchanted dwelling of some Sleeping Beauty, of a princess of an unknown world, or of a planet that could not be our own.

We pass before some little interior gardens, which are, according to the Japanese custom, miniature reductions of very wild places, — unlooked-for contrasts in the centre of this golden palace. Here also time has passed, throwing its emerald upon the little rocks, the tiny lakes, and the small abysses; sterilizing the little mountains, and giving an appearance of reality to all that is minute and artificial. The trees, dwarfed by I know not what Japanese process, have not grown larger; but they have taken on an air of extreme old age. The cycas have acquired many branches, because of their hundreds of years; one would call the little palms of multiple trunks, antidiluvian plants; or rather massive black candelabra, whose every arm carries at its extremity a fresh bouquet of green plumes.

What also surprises us is the special apartment chosen by this Taïko-Sama, who was both a great conqueror and a great emperor. It is very small and very simple, and looks upon the tiniest and the most artificial of the little gardens.

The Reception Hall, which they showed me last of all, is the largest and the most magnificent. It is about fifty metres long, and, naturally, all in golden lacquer, with a 65 high and marvellous frieze. Always no furniture; nothing but the stages of lacquer upon which the handsome lords on arriving placed their arms. At the back, behind a colonnade, is the platform, where Taïko-Sama held his audiences, at the period of our Henri IV. Then it is that one dreams of these receptions, of these entrances of brilliant noblemen, whose helmets are surmounted by horns, snouts and grotesque figures; and all the unheard-of ceremonial of this court. One may dream of all this, but he will not clearly see it revive. Not only is the period too remote, but it is too far away in grade among the races of the earth; it is too far outside of our conceptions and the notions that we have inherited regarding these things. It is the same in the old temples of this country; we look at them without understanding, the symbols escape us. Between Japan and ourselves the difference of origin has made a deep abyss.

“We shall cross another hall,” the bonze said to me, “and then a series of passages that will lead us to the temple of the palace.”

In this last hall there are some people, which is a surprise, as all the former ones were empty; but silence dwells there just the same. The men squatting all around the walls seem very busy writing; they are priests copying prayers with tiny pencils on rice-paper to sell to the people. Here, upon the golden background of the walls, all the paintings represent royal tigers, a little larger than their natural size, in all attitudes of fury; of watching, of the hunt, of prowling, or of sleep. Above these motionless 66 bonzes they lift their great heads, so expressive and wicked, showing their sharp teeth.

My guide bows on entering. As I am among the most polite people in the world, I feel obliged to bow also. Then the reverence that is accorded to me passes all along the hall, and we go through.

Passages obstructed with manuscripts and bales of prayers are passed, and we are in the temple. It is, as I expected, of great magnificence. Walls, ceilings, columns, all is in golden lacquer, the high frieze representing leaves and bunches of enormous peonies very full-blown and sculptured with so much skill that they seem ready to drop their leaves at the least breath to fall in a golden shower upon the floor. Behind a colonnade, in the darkest place, are the idols and emblems, in the midst of all the rich collection of sacred vases, incense-burners, and torch-bearers.

Just now it is the hour of Buddhist service. In one of the courts, a gong, with the deep tones of a double-bass, begins to strike with extreme deliberation. Some bonzes in robes of black gauze with green surplices make a ritualistic entrance, the passes of which are very complicated, and then they go and kneel in the centre of the sanctuary. There are very few of the faithful; scarcely two or three groups, which seem lost in this great temple. There are some women lying on the matting, having brought their little smoking-boxes and their little pipes; they are talking in very low voices and smothering the desire to laugh.

However, the gong begins to sound more rapidly and the 67 priests to make low bows to their gods. It sounds still faster, and the bows of the bonzes quicken, while the priests prostrate themselves upon their faces upon the earth.

Then, in the mystic regions something happens that reminds me very much of the elevation of the host in the Roman cult. Outside, the gong, as if exasperated, sounds with rapid strokes, uninterruptedly and frantically.

I believe that I have seen everything now in this palace; but I still do not understand the disposition of the halls, the plan of the whole. If alone, I should soon become lost in it, as if in a labyrinth.

Happily, my guide comes to take me out, after having put my shoes on me himself. Across new halls of silence, passing by an old and gigantic tree, which has miraculous properties, it seems, having for several centuries protected this palace from fire, he conducts me through the same gate by which I entered and where my djin are waiting for me.