[Click on the footnote symbols and you will jump to the note on the bottom on the page. Then click on the symbol there and you will be magically transported back to where you were in the text.]

From Romantic Castles and Palaces, As Seen and Described by Famous Writers, edited and translated by Esther Singleton; New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1901; pp. 105-114.

[105]

FUTTEHPORE-SIKRI, INDIA.

THE ruins of Futtehpore, the Versailles of the great Akbar, cover the summit of a hill twelve miles from Bhurtpore. On leaving that town, we traveled across a succession of monotonous plains alternately composed of marshes and rocky deserts. The horizon was unbounded, except on the east, where lay the hill of Futtehpore, the fantastic outline of which caught the rays of the rising sun. Even from afar, the eye is struck by the number and size of the buildings, which a royal caprice has erected in the midst of this desert: one would take it for a large and populous city. Those long lines of palaces with their gilded domes and pinnacles could never had been built to be so soon abandoned to solitude. The scene becomes grander the nearer you approach. On arriving at the foot of the hill, the road passes under a majestic gateway, beyond which are the long, silent streets; the palaces still standing perfect and entire amidst the ruined dwellings of the people; with the fountains and the magnificent gardens, wherein the pomegranates and the jessamine have grown for centuries. The whole scene is of imposing grandeur; and the hand of time has fallen so lightly upon it that one might take it for a town very recently deserted by its inhabitants, or one of the enchanted cities of Sinbad the Sailor.

106The bigarri,1 whom we had taken with us from the village of Sikri, conducted us to a bungalow which is maintained by the English Government for the accommodation of travellers. This bungalow, which was once the ancient kutchery2 of Akbar, is built of red sandstone, and surrounded by a beautiful verandah supported by columns. It is situated on the northern extremity of the plateau, and overlooks the town on one side and the front of the zenanah on the other. An old Sepoy is placed in charge of the edifice, which contains two comfortably furnished apartments.

The foundations of Futtehpore, “the Town of Victory,” were laid by Akbar in 1571, and the ramparts, city, and palace were all completed with extraordinary rapidity. Akbar was attracted to this desert by the sanctity of a Mussulman Anchorite, Selim Shisti, who inhabited one of the caverns on the hill. Attracted by the situation, he built himself a palace, and finally, being unwilling to give up the society of the holy man, he resolved to establish there the capital of his empire. In a few years this desert spot was transformed into a large and populous city; but the death of Selim soon put an end to this prosperity. Akbar then saw the folly of trying to place his capital in the midst of these sterile plains, unapproached by any of the great rivers, more especially as he possessed the unusually favorable situation of Agra. His resolution was promptly taken. In 1584, he abandoned Futtehpore with all its 107 grandeur, and carried off the whole population to people his new capital of Agra. The evacuation was complete; none of the successors of Akbar cared to carry out his foolish project, and very soon the only inhabitants of Futtehpore were wild animals and a few anchorites. One is almost tempted to think that Akbar built Futtehpore for the sole purpose of giving posterity some idea of his greatness in leaving this monument of his capricious fancy.

The fame of Selim still attracts thousands of pilgrims to his tomb, where they assemble at certain seasons of the year; and, to supply the wants of these devotees, two villages have sprung up on the site of the deserted town, one called Futtehpore, and the other Sikri; and it is by this double appellation of Futtehpore-Sikri that the ruins are generally known. Apart from their beauty, which all must admire, they are of special interest to the archæologist as being the work of a single individual, and therefore a perfect specimen of the style of architecture of his epoch. From their marvellous state of preservation, you can trace, step by step, the mode of life of the great Akbar, and can form a just idea of Indian manners and customs in the Sixteenth Century. Everything still breathes of the magnificence of that Eastern Court the fame of which was carried to Europe by contemporary travellers, whose tales were looked upon as fables, and the wealth and splendour of which excited later the avarice and cupidity of the Western nations.

The tomb of Selim, the imperial palace, and some of the dwellings of the Mogul grandees are almost entire. 108 They form a compact group, one mile in length, which occupies the summit of a hill 180 feet high. This hill furnished the whole of the material of which they are built, which is a fine sandstone, varying from purple to rose colour. The stone has been left unornamented throughout; but the architects have avoided the monotony of the colour by artistically arranging its various tints. The mass is now softened by time; and one of its chief beauties is this mellow colouring, which blends ground and building in one, making the latter appear as though carved out of the peaks of the mountain.

The imperial palace lies to the east of the tomb. It is a vast collection of separate buildings connected by galleries and courtyards, and covering an area at least equal to that occupied by the Louvre and the Tuileries.

The first building you come to on leaving the tomb used to contain the private apartments of the emperor. It now goes by the name of tapili, or guard-house, from the fact of its being inhabited by the handful of soldiers who are employed to keep off marauders from the ruins. The palace is built with great simplicity, its exterior being nothing but a blank wall, with a small court in its centre, into which the galleries on the different stories open. On one side is a colonnade, profusely ornamented in the Hindoo style; this was the verandah of the apartment of Akbar’s favourite wife, and the mother of Jehangir: and at the end of an open space which extends in front of the palace is the kutchery, now covered into a bungalow for travellers.

A ruined gallery leads from the tapili to the Imperial 109 zenanah, which is surrounded by a high wall. Each princess was allotted a separate palace in this enclosure, with its own gardens, etc., constructed according to her own tastes and wishes. The first of these was the palace of the Queen Mary, a Portuguese lady whom Akbar had espoused; in the apartments of which are numerous frescoes, amongst others one representing the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. It is a matter of surprise to find a Mussulman prince, in the Sixteenth Century, with such tolerant views as to allow in his palace a thing so opposed to the principles of his religion; but it does not astonish one in such an enlightened man as the great Akbar. Wishing to put an end forever to the subjects of discord which divided the nations of his empire, he devised the plan of creating a new religion which should unite the sympathies of all. For this purpose he assembled a general council which was attended by the priests of all the religious denominations of India, and even by some of the Christian missionaries from Goa; and to them he submitted his project: but nothing resulted from the discussion. In spite of this the emperor compiled a voluminous work on the different religions of the world, viz., Christianity, Judaism, Islamism, and the various Hindoo sects, in which he displayed very liberal and enlightened views.

From the palace of Queen Mary you enter a court, surrounded by apartments, and almost entirely occupied by a basin of vast dimensions, in the centre of which is an island built on a terrace, and reached by four stone foot-bridges. At the extremity of this court, there is a 110 pavilion, the walls and pillars of which are enriched with fine sculptures; its rooms overlooking on one side the ornamental tank, and on the other a garden still ornamented with shrubberies and fine trees. This was the abode of one of Akbar’s wives, the Roumi Sultani, daughter of one of the Sultans of Constantinople.

On a high terrace, to the right of this palace, is the emperor’s sleeping-apartment; the ground-floor containing a spacious hall with sculptured columns, which is half filled up with rubbish.

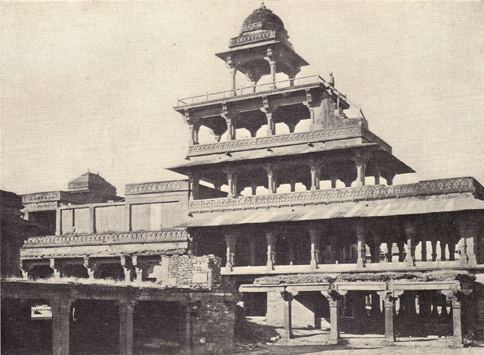

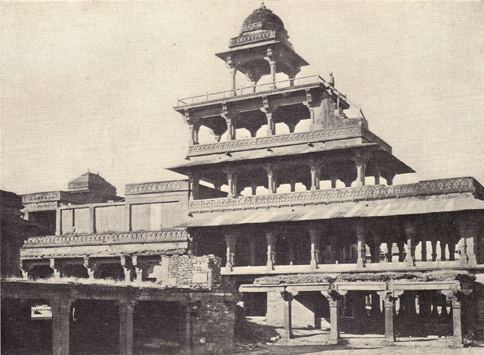

On the west of the zenanah, rises a fanciful construction, called Pânch Mahal — “the Five Palaces,” — which consists of four terraces, supported by galleries rising one above another, and gradually diminishing in size towards the top, where they terminate in a dome sustained by four columns. It resembles the half of a pyramid, and has a very curious effect. The thirty-five pillars which support the second terrace are all different, comprising almost every style and some very remarkable specimens of original architecture. It is a valuable architectural collection. There has been much discussion as to the design of the building, since the open galleries could not possibly have been intended for habitation. Its position against the walls of the zenanah, the interior of which it overlooks and communicates with, leads to the supposition that it was assigned to the eunuchs; but in any case it was a fanciful idea of the architect. In the little court which surrounds the Pânch Mahal are some very curious detached buildings for the accommodation of the servants of the harem. The architect 111 evidently wished to give them an appearance most befitting their use; and, as there was no wood at his disposal, he minutely copied in stone those light constructions which serve in the palaces of India as a shelter for the lower servants. The roof, formed of slabs of stones, is carved to imitate thatch, and is supported by the same network of beams which would be used for a lighter material than sandstone. In a word, they are sheds built of sculptured stone.

After passing through the galleries of the Pânch Mahal, you come out upon the principal court of the palace, called the Court of the Pucheesee; on one side of which are the walls of the zenanah, and on the other the apartments of the ministers and the audience-chambers.

Pucheesee* is a game of great antiquity, which the Indians have always been passionately fond of; and it is played with pawns on chess-boards greatly resembling those used in Europe. There are four players, with four pawns apiece; and the moves are regulated by throwing the dice, the object being to get your four pawns into the centre of the board. The game of pucheesee was played by Akbar in a truly regal manner; the court itself, divided into red and white squares, being the board, and an enormous stone, raised on four feet, representing the central point. It was here that Akbar and his courtiers played this game; sixteen young slaves from the harem, wearing the players’ colours, themselves represented the pieces, and moved to the squares according to the throw of the dice. It is said that the emperor took such a fancy to playing the game on this grand scale that he had a court for pucheesee constructed in all 112 his palaces; and traces of such are still visible at Agra3 and Allahabad.

To the north of this court and on the same sides as the Pânch Mahal is a palace, built with great simplicity, and in such a good state of preservation that you might mistake it for a modern building. One wing is a perfect labyrinth of corridors and passages, in which the ladies of the Court amused themselves with their favourite games of “aukh-matchorli,” or blind-man’s buff, and hide-and-seek; and before it rises a kiosk of Hindoo architecture, called the Gooroo-ka-Mundil, #8220;Temple of the Mendicant.” The emperor, in order to show his regard for the religion of the majority of his subjects, entertained a Gooroo, or religious mendicant of the Saïva sect, and even had this temple built for him and his co-religionists.

A little farther on and facing the zenanah is one of the most beautiful buildings of Futtehpore, consisting of a 113 graceful pavilion of one story, surmounted by four light cupolas. This is the Dewani-Khas, or Palace of the Council of State. The simplicity of its outline, its square windows and handsome balcony, remind one of our modern buildings. It is, however, quite in accordance with the character of Akbar, who, as well in architecture as in religion and government, never copied his predecessors. The interior of the Dewani-Khas is a large hall the whole height of the edifice, in the centre of which is an enormous column of red sandstone, which terminates at some distance from the ceiling in a large capital magnificently sculptured. This capital forms a platform, encircled by a light balustrade, from which diverge four stone bridges, leading to four niches in the corners of the building; and a staircase hidden in the wall leads to a secret corridor, which communicates with the niche. It is one of the strangest fancies of the architect of Futtehpore.

On the occasion of a council being assembled, the emperor took his place on the platform, his ministers occupying the niches; while the ambassadors and other personages who were called into their presence remained in the hall at the foot of the column, and were unable to judge of the impression which their communication produced on the council.

A long gallery, partly in ruins, leads from the Dewani-Has to the Dewani-Am, or Palace of the Public Audiences. It is a small building, one side of which overlooks the Court of the Pucheesee, and the other a large court surrounded by colonnades.

114The chronicler Aboul Fazel says that at certain hours the people were admitted into this court. After the council the emperor repaired to the Dewani-Am, where, after having put on his robes of state, he seated himself on a tribune overlooking the court. Here he remained for some time, inquiring into and redressing the grievances of the people, and receiving the strangers who flocked to his court. According to tradition, it was here that he received the Jesuits of Goa, who brought him the leaves and seeds of tobacco; and it was at Futtehpore that Hakim Aboul Futteh Ghilani, one of Akbar’s physicians, is supposed to have invented the hookah, the pipe of India.

It would take too long to describe every part of this vast palace in detail, for, besides what I have already noticed, there are the baths, the mint, the barracks, and numerous other buildings, all in ruins.

Footnotes

1 A guide for travellers, furnished by the villages.

2 Court of the magistrate attached to the palace.

3 “The following account of Akbar’s Pachisi-board is from an old, Agra periodical: — The game is usually played by four persons, each of whom is supplied with four wooden or ivory cones, which are called ‘gots,’ and are of different colours for distinction. Victory consists in getting these four pieces safely through all the squares of each rectangle into the vacant place in the centre, — the difficulty being that the adversaries take up in the same way as pieces taken at backgammon. Moving is regulated by throwing ‘cowries,’ whose apertures falling uppermost or not, affect the amount of the throw by certain fixed rules. But on this Titanic board of Akbar’s, wooden or ivory ‘gots’ would be lost altogether. Sixteen girls, therefore, dressed distinctively — say four in red, four in blue, four in white, four in yellow — were trotted up and down the squares, taken up by an adversary, and put back at the beginning again; and at last, after many difficulties, four of the same colour would find themselves gliding into their dopattas together in the middle space, and the game was won.” — Bholanauth Chunder.

Elf.Ed. Notes

* Pucheesee, is the game now known as parcheesi. It is also spelled pachisi in footnote 3 above, by the author of the essay.