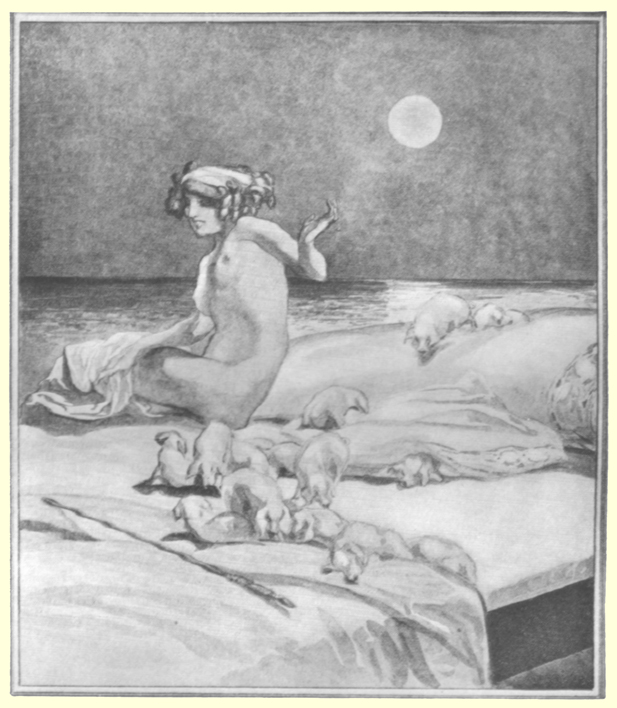

From The Works of Aretino, Translated into English from the original Italian, with a Critical and Biographical Essay by Samuel Putnam, Illustrations by The Marquis de Bayros in Two Volumes, Volume I., Chicago: Pascal Covici, 1926; pp. 113-131.

THE ART OF THE COURTEZAN

It is not enough to have pretty eyes and blonde hair.

The Second Part of the Capricious Dialogues of Aretino, in which Nanna, on the first day, teaches her daughter, Pippa, how to become a whore and on the second, recounts to her the manner in which men betray the wretched women who trust in them; while on the third day, Nanna and Pippa, seated in a garden, listen to a Godmother and a Nurse conversing on the art of the procuress.

THE VOCATION

I’ll be one yet.

NANNA: What wrath, what anger, what madness, what restlessness, what heart-flutterings and fainting fits are these, fastidious girl that you are?

PIPPA: I am angry because you do not want to make me a courtezan, as my godmother, Nonna Antonia, advised you.

NANNA: It is time for dinner now.

PIPPA: You’re a step-mother, ugh!

NANNA: Cry on, little baby.

PIPPA: I’ll be one yet.

NANNA: Lay aside that pride of yours, lay it aside, I tell you, for if you do not change your ways, Pippa, if you do not change them, you will never have a diaper to your rump; for today there are so many whores that the one who does not work miracles with her wits will never have a dinner to go with her afternoon lunch; and it is not enough to be a fine piece of flesh, to have pretty eyes and blonde hair; art or fate is far more important; the rest is bubbles.

PIPPA: So you say.

NANNA: And so it is, Pippa, but if you lean on my bosom, if you open your ears to my precepts, you will be very, very, very well off.

PIPPA: If you will hasten to make me a signora, I will open them soon enough.

NANNA: If you will listen to me instead of playing with every straw that blows, with your head full of whims, as it used to be when I tried to teach you something 116 useful, I swear to you by these paternosters I am always chewing over that, within fifteen days at the longest, I will take the matter in hand.

PIPPA: May God grant it, mamma!

NANNA: May you will it, rather.

PIPPA: I do will it, dear mammina, mammina d’oro.

THE A B C’S

For they deceive the poor courtezans.

NANNA: The art of entertaining your friends with a certain manner of gossiping, which never comes to the point of hatred, is the lemon squeezed into the frying-pan and the pepper sprinkled over the contents of the pan. It is a gentle novelty, when you find yourself at cross-roads with different generations, to satisfy them all with a little babbling, which never becomes boresome, and which is useful in filling in the pauses when someone comes in to see you. And since the customs of others are of more importance than individual fantasies, study, spy out, anticipate, consider, be attentive to, subtly analyze and sift the brains of all. Here you have a Spaniard, dandified, odoriferous, dirty. And if the Our Highnesses which he hurls upon your head and the kisses which he sugars your hand were a form of alchemy, between them and his ceremonious manners you would have the income of an Agostino Chigi. 1

PIPPA: I know well enough that there’s nothing to be got from them.

NANNA: You have nothing else to do but to provide smoke for their wind and breath for those belly-ripping sighs which they know so well to give; bow then to their bows, kissing not merely the hand but the glove, and if you do now want to be paid in the coin of Milan, get rid of them the best way you can.

PIPPA: I shall do so.

NANNA: Be firm. As for a Frenchman, open to him right away, open in a flash; and while he is embracing you as 118 gaily as possible and kissing you in a careless fashion, cause the wine to be brought out, for with this nation, it is necessary to step out of the nature of prostitutes, who ordinarily would not give you a beaker of water if they saw you were dying; and then, with a couple of slices of bread, set yourself to make a domestic sort of love. And without standing too much on the conveniences, take him as your bed-fellow, chasing away all the others with a pretty manner. In the meanwhile, it will appear that you are about to hold a carnival, so much stuff will have rained down in the kitchen; and if he gets out of your claws with a shirt to his back, he is lucky, for these butlers, who know better how to lose than how to gain, and who more readily forget themselves than remember an injury which has been done them, give no heed at all whether you rob them or not.

PIPPA: The French are all right; blessed be the French.

NANNA: But remember, they give denarii and the Spaniards cups. The Germans now are of another stamp, and with them it is necessary to be upon your guard. I speak of the merchants, who fall into love, I will not say as they do into wine, because I have known some who were most polished, but, let us say, as they do into Lutheranisms. They will give you great ducats, if you know how to approach them, never permitting them to be your lovers nor to make or talk love. Skin in secret those who allow themselves to be skinned.

PIPPA: That is a good thing to remember.

NANNA: Their nature is hard, bitter, and bestial, and when they get a thing into their heads, God alone can take it out; and so, grease them as gently as you know how.

PIPPA: What else would there be for me to do?

NANNA: There is one thing I should like to warn you about, and yet I do not dare to do it.

PIPPA: What?

NANNA: Nothing.

119PIPPA: Tell me, I want to know.

NANNA: I do not want to tell you, because I should be blamed for it, and it would be a sin.

PIPPA: Then why did you give me a fancy for hearing it?

NANNA: I will tell you one thing, that if you have a chance to mingle with Jews, you should do so, but with dexterity, finding as an excuse a desire to purchase espaliers, bed-furnishings, and similar trifles; and you will see there will be some of them who will take you to the bank, advance you all their usuries and all their pilferings, throwing in even their discounts; and if they stink like dogs, let them stink.

PIPPA: I thought you really had something to tell me.

NANNA: So I had. The odor with which they reek put me in mind to tell you. But do you know what? Sailors with all their fine gains are always in danger of the galleys, of chains, of drowning, of falling into the hands of the Turks or of Barbarossa, of shipwreck, of eating dry or vermin-infested bread, of drinking vinegar and water, and of all the other discomforts which I have heard tell there are; and if the one who goes to sea takes no thought of winds or rains or any hardships whatsoever in order to dispatch his cargo, surely a courtezan ought to make light of the smell of a few Jews.

PIPPA: You make the most beautiful comparisons. But if I associate with them, what will my friends say?

NANNA: What would you have them say, if they know nothing about it?

PIPPA: How do you mean, nothing?

NANNA: If you say nothing about it to them, the Jew, since his bones are not marked, will be as silent as a thief.

PIPPA: In that way, it’s all right.

NANNA: I can see a Florentine coming to your room with his chitter-chatter. Make love to him, for the Florentines outside of Florence are like those persons who, with a 120 full bladder, are unwilling to go urinate out of respect for the place in which they find themselves, but when they get outside, they deluge a wide, wide space. I will tell you that they are more generous abroad than they are at home; beyond this, they are virtuous, gentle, polished, sharp and pungent; and if they give you nothing else than their gallant words, do you not think you could be content with those?

PIPPA: Not I.

NANNA: That was merely a method of speaking on my part; they must spend as much as possible, give papal dinners and feste in quite a different manner from what the others do; and then, their tongue is pleasing to all.

PIPPA: And now let’s speak a little of the Venetians.

NANNA: I do not want to tell you about them, for if my words are not equal to their merits, I shall be told that I am deceived in the love I have for them 2 and certainly I am not deceived at all, for they are gods, and the patrons of everything, and the finest youths, the finest men and the finest old men that there are in the world; all the rest of the world will appear to you like wax-work soldiers by comparison, and although they are proud, having a right to be, they are the very image of kindness itself. And while they live the life of merchants, in accordance with our custom, they do it on a royal scale, and he who is on the right side of them is fortunate. Everything else is a joke, saving the grace of those old money bags who have piles and piles of ducats and who, no matter how much it thunders or rains, would not give you so much as a bagattino.

PIPPA: God keep them.

NANNA: He does it well enough. . . . And now to jump from Florence to Sienna, I will tell you that the Sienese madmen are gentle fools, although for a number of years 121 they have been turned wicked, according to the chatter of some; and according to the experience I have had of men, the odds appear to me to be that they hold, in the matter of gentleness and virtue, to the Florentine, but they are not so crafty nor so dog-like, and he who knows how to deceive can flay and shear them alive. Moreover, they are big fellows down below, and their practices are pleasing and honorable.

PIPPA: They will do for me.

NANNA: Yes, certainly. And now let’s on to Naples.

PIPPA: Don’t talk to me of that town; it gives me the asthma to think of it.

NANNA: Listen, Signora, even though it be a death in life. The Neapolitans are made to drive away sleep and to provide you with a fine bellyful some day of the month when you have the whim in your head, alone or in the company of someone else, it does not matter whom. I can tell you that their fripperies rise to heaven: talk of horses — they have the first that came from Spain — of clothing — two or three wardrobes full — money in piles, and all the belles of the kingdom are dying for them directly; and if you drop your handkerchief or your glove, they will recover it for you with the most gallant parables that were ever heard in a Capuan chair, si, Signora.

PIPPA: What sport.

NANNA: I once wanted to get rid of a certain traitor by the name of Giovanni Agnesi, the very scum of all filth, if I am to force myself to counterfeit him in words, although the hangman could not counterfeit him in deeds; and at the sight of this, a certain Genoese burst into laughter, whereupon I turned on him and said: “My proud Genoa, proud because you know how to buy beef without bones, we others can teach you a thing or two.” And it was true, because they are the subtlest of 122 the subtle and the sharpest of the sharp, and they are altogether too good managers and cut the thing just as it should be cut and they will give you not the least bit too much. For the rest, I cannot tell you what glorious lovers they make, what gentle Neapolitan and un-Spanish breeding they show, reverent, making what little they give you appear as sweet as sugar, and never failing to give you that little. You must always know how to get the better of them and measure your gifts as they measure theirs; and, without turning your stomach, with a pleasant speech in your throat, with your nose and with a sigh, take things as they come.

PIPPA: The Bergamasks have more grace than their speech.

NANNA: They also are gentle and dear, that is certain. But now, let us come to the Romanians. Daughter, if you delight in eating bread and buffalo cheese with sword points and spear heads for a salad, pickled in the fine bravados which their great-grandfathers used to hurl at the town sheriffs, associate with them. The short of it is, on the day of the Sack, 3 they defecated upon us (speaking with all reverence), and Pope Clement has no regard for them any more.

PIPPA: Don’t forget Bologna, if for no other reason than for love of the count and of the cavalier who is of our house.

NANNA: Forget them, ah? What would the rooms of whores be without the shadow of those long-winded stocks? Born here solely for the purpose of making numbers and shade, says the canzona; I am speaking of love and not of arms, said Friar Mariano. A fine young chicken of twenty years old told me that she had never seen madmen who were plumper or better clad. And so, do you, Pippa, make a feast for them as you would for courtiers, and take your pleasure in their thoughtless and foolish 123 conversation; and such a practice as this is by no means without its use, and it will be more useful than any other, if they delight as much in she-goats as they do in kids. As for the rest of the Lombardians, who are snails and great dandies, treat them in the whorish manner, taking from them what you can get, giving to each of them a “cavalier,” throwing in a “Count” for a moustache, with a “Signor, si” and a “Signor, no”; for such deceits as these do not spoil the soup, and it is honest to indulge in them and even to boast of them; for they deceive the poor courtezans, and moreover, those houses in which such customs are to be found are praised above all others.

FOOTNOTES

1 The Crœsus of Rome, Aretino’s patron.

2 Aretino never loses a chance to eulogize his own loved Venice.

3 Of Rome.

THE SCAR

And those were the denarii I spent on this house.

NANNA: A certain official who in the course of his duties had taken two thousand ducats from the port of entry was enamored of me, and so foolishly that it atoned for all his sins. This fellow was in the habit of spending by the moon, and anyone who wanted to get anything out of him, when he was not in the mood to give it, had to do some astrologizing. And what is more to the point, his bizarre nature started the day he came into the world, and whenever a word was spoken that was not to his liking, he would fall into a fury, and his hand would hunt his dagger, and a slash in the face was the least you had to fear with him. For this reason, the courtezans fled his company as countrymen do the rain. I, who had taken this old sock to new-foot, was in the habit of keeping him company at every meal, and although he played his asinine jokes on me, I waited patiently, thinking I would play one on him which would make up for everything. I thought and though until I found the way, and what do you think it was I did? I took a certain painter into my confidence, by name Maestro Andrea, or I will say it was that anyway; and I made an agreement with him that he was to be in waiting and hidden under my bed, with his colors and brushes, to paint a scar on my face when the time came. And then, I received Maestro Mercurio (bless his memory), if you remember him.

PIPPA: I remember him.

125NANNA: And I told him that, when I should send for him on such and such an evening, he was to come with oakum and eggs; and he, to be of service to me, did not leave his house on that particular feast day when I wanted to do this. And now, look you, Maestro Andrea is under the bed and Maestro Mercurio in his house, and I am with this official at table; and when we had just about finished dinner, I reminded him of a certain chamberlain of his Reverence, to whom he did not even want me to speak, and whom he had driven out of the house. Now it did not take much raising for a wind that was already up, and calling me a prostitute, a low woman and a bandiera, he was hoping that I would ram the lie down his throat; and he gave me a blow on my cheek with his dagger, a blow that I could feel, and then I, who had at hand some oil of lacquer which had been given my by Maestro Andrea, dipped my hands in it and smeared my face, and with the most terrible cries that a woman ever gave I made him believe that he really had succeeded in cutting me. Thereupon, as frightened as one who had murdered another, he took to his legs and fled to the palace of Cardinal Colonna, and locking himself in the room of a courtier who was his friend, he kept moaning to himself: “Alas, I have lost my Nanna, Rome and my offices.” I, in the meanwhile, locked myself in my room, alone with my elderly servant maid, and Maestro Andrea, coming out of his nest, in a trice painted a scar across my right cheek, which was so real that when I looked in the mirror I trembled with fear. At this Maestro Mercurio came in, saying: “There seems to be something wrong here.” And having assisted the drying of the colors by applying oakum with oil of rose water and the white of an egg, he bandaged up the wound right gracefully, and then going out into the hall where a crowd had collected, he said: “She is not able to come out.” And so the report spread throughout 126 Rome, and the rumor came to the would-be murderer, who wept like a child that is beaten.

Morning came, and with it the doctor, and with a great farthing candle lighted in his hand he applied the cure, until I do not know how many persons who had stuck their heads through the door of the room and who had filled all the windows, began weeping at the sight, and I cannot tell you how many of them, unused to looking on so cruel a wound, fainted dead away. And so the rumor became public that my face was spoiled forever, and the evil-doer began sending money, medicines and doctors, seeking thus to avoid the sheriff. When eight days had passed, I let it be known that I had escaped, but with a mark more bitter than death to a courtezan; and my friend, wishing to quiet the thing with his scudi, kept sending this and that; and I so employed my friends and patrons that it came to be understood I was only to be seen by a certain shell-bean of a Monsignor, who acted as go-between. In short, five hundred ducats were disbursed for my injury, and fifty more for doctor and medicines; and then I pardoned him, that is, I promised not to prosecute him before the governor, desiring from him only peace and security. And those were the denarii which I spent on this house, not counting the garden, which I have added since.

PIPPA: You were a good man, mamma, to do such a thing as that.

NANNA: But we have not yet come to the halleluia, and I should not come to an end in a year if I wanted to tell you everything; for in good faith, I have not squandered the time that I have lived, my faith no, I have not squandered it.

PIPPA: I knew that to begin with.

NANNA: And then, finding that the five hundred, with the fifty ducats, had merely touched my palate, I thought up most whorishly a piece of whorish malice, and what do 127 you think it was? I sent for a certain Neapolitan, a swindler of the swindlers, with the reputation of possessing a secret by which he could remove every sign of a scar which had been left on the face. 1 He came to me and said: “When a hundred scudi have been deposited I will make your face appear as smooth as this.” And he showed me the palm of his hand. I began writhing and said, with a feigned sigh: “Go and tell that miracle to the one who is the cause of my being the way I am.” When he wanted to say more, I turned upon him, calling “Tom cat! Tom cat!” The swindler, with his all too fine clothes, took his departure, went to the official and laid before him an account of what he proposed to do. And now, would you believe it, the crucified wretch, despairing of ever having anything more to enjoy, deposited the hundred. But what use to prolong this story? The scar which was not there went away with a little holy water which I sprinkled on my face six times, with a few words which appeared to be saying a mirabilium, but which really said nothing. And so it was, the hundred pleasures, as the Greek says, came into my hand.

PIPPA: Welcome and a good year.

NANNA: But wait. When the rumor spread that I had been left without a trace in the world, everyone who had a scar under his moustache came running to the swindler’s rooms as the synagogues would run about the Messiah, if he were suddenly to appear in the Jewish piazza. The traitor, filling his purse with earnest-money, packed up and left, trusting to the discretion he thought I ought to show as a reward for the ducats which he had put me in the way of gaining.

PIPPA: The official, did he hear and believe this?

NANNA: He heard it, and he did not hear it; he believed it, and he did not believe it.

128PIPPA: That’s enough.

NANNA: But the poison is in the tail.

PIPPA: What, is there more to come?

NANNA: The best part is to come. The big booby, after so many disbursements, for the sake of which, it is said, he sold a knighthood, was finally reconciled with me through the offices of go-betweens and by means of letters. These ambassadors kept telling me about his passion, and he came, himself, to throw himself at my feet, seeking the words that would put him back in my good graces. So I went with him to the shop of the painter, who had painted a tablet for me with a miracle, which I told him he should carry in person to Loreto. When he fixed his eyes on it, he saw himself depicted there with a dagger in his hand and about to slash me, a poor woman. This was nothing to what he read beneath it: “I, Signora Nanna, adoring Messer Maco, thanks to the devil which entered his cup, had from him as a reward for my adoration this wound of which that Madonna to whom I hang up this votive offering has cured me.”

PIPPA: Ha, ha!

NANNA: When he read this, he made a face like those which bishops make on reading their epitaphs, under the heels of the demons who flay them when they are excommunicated. Returning home off all his hinges, by means of a new dress he made me promise to take his name off the tablet.

PIPPA: Ha, ha, ha!

NANNA: The conclusion is this: The fine fellow gave me, besides, the denarii to go there, where I had no intention of going; and there was no need for me to go, for I forced him to get me an absolution from the Pope.

PIPPA: Is it possible he was so senseless that when he came to you he did not see your face had never had a scar?

NANNA: I will tell you, Pippa, I took something or other, 129 like the back of a knife, and fastened it to my face; I kept it there all night, and as soon as he appeared. I removed it. And then, for a while, you would have believed, seeing the livid spot it left, that it was the same sort of scar you see about a bit of bruised flesh, such as would have been left by a knife-wound that had healed.

PIPPA: I see.

FOOTNOTES

1 Plastic surgery!

A NEW RUSE

Tell me if it isn’t a joke for whores to know how to keep themselves.

NANNA: I want to tell you that one about the crane, and then I shall finish the business I have with you.

PIPPA: Tell it first.

NANNA: I pretended that I wanted a crane to eat with vermicelli, and not being able to buy any, one of my lovers was forced to go out and kill one with his rifle, and so I had it. But what do you think I did with it? I took it to a delicatessen keeper, who knew all my subjects, or vassals, as Gianmaria the Jew called those of Verucchio. But I forgot to tell you, I made him who gave it to me swear to say nothing about it, and when he asked me what the difference was, I replied that I did not want to be taken for a glutton.

PIPPA: You did right. And now to the delicatessen keeper.

NANNA: I gave him to understand that he was not to sell it except to someone who bought it for me. And he, who had served me in such matters on other occasions, understood me at once. No sooner had he hung it up in his shop than one of those who knew my fancy was upon his back, saying, “How much do you want for it?” “It is not for sale,” replied the knave, in order to make him want it the more, “and besides, it costs too much.” The other swore an oath, saying, “Let it cost what it will.” He ended by taking out a ducat and sending the bird to my house by his groom, thinking I would believe that it had been given to him by a Cardinal. I, making sport, sent it back, cut up as it was, to be sold again. What then? The crane was 131 bought by all my friends, and always for a ducat, and finally it came to my house. And now, Pippa, tell me if it isn’t a joke for whores to know how to keep themselves.

PIPPA: I am astonished.”

Here ends the First Day

of the

Pleasing Dialogues of M. Pietro Aretino.