From History of Flagellation Among Different Nations. New York: Medical Publishing Co., 1930: pp. 86-98.

THE example which so many illustrious personages has given of voluntarily submitting to flagellation, and the pains which monks had been at to promote that method of mortification by their example likewise, as well as by the stories they related on that subject, had as we have seen, induced the generality of people to adopt the fondest notions of its efficacy. But about the year 1260 the intoxication became as it were, complete. People, no longer satisfied to practice mortification of this kind in private, began to perform them in the sight of the public under pretence of greater humiliation; regular associations and fraternities were formed for that purpose, and numerous bodies of half-naked men began to make their appearance in the public streets, who after performing a few religious ceremonies contrived for the occasion, flagellated themselves with astonishing fanaticism and cruelty.

The first institution of public associations and solemnities of this kind must needs have filled with surprise all moderate persons in those days; and in fact we see that historians of different countries who lived in the times when these ceremonies were first introduced, have taken much notice of them, and recorded 87 them at length in their histories or chronicles. I will lay a few extracts of these different books before the reader, it being the best manner, I think, of acquainting them with the origin of these singular flagellating solemnities and processions which continue in use in several countries.

The first author from whom we have a circumstantial account on that subject is the monk of St. Justina, in Padua, whose Chronicle Wechelius printed afterwards at Basil. He relates how the public superstitious ceremonies we mention made their first appearance in the country in the neighbourhood of Bologna, which is the spot where, it seems, they took their first origin, and whence they were afterwards communicated to other countries. The following is the above author’s own account.

“When all Italy was sullied with crimes of every kind, a certain sudden superstition hitherto unknown to the world, first seized the inhabitants of Perusa, afterwards the Romans, and then almost all the nations of Italy. To such a degree were they affected with the fear of God, that noble as well as ignoble persons, young and old, even children five years of age, would go naked about the streets without any sense of shame, walking in public, two and two, in the manner of a solemn procession. Every one of them held in his hand a scourge made of leather thongs, and with tears and groans they lashed themselves on their backs till the blood ran; all the while 88 weeping and giving tokens of the same bitter affliction as if they had really been spectators of the passion of our Saviour, imploring the forgiveness of God and his Mother, and praying that He who had been appeased by the repentance of so many sinners, would not disdain theirs.

“And not only in the day time but likewise during the nights, hundreds, thousands and tens of thousands of these penitents ran, notwithstanding the rigour of the winter, about the streets and in churches with lighted wax-candles in their hands, and preceded by priests who carried crosses and banners along with them, and with humility prostrated themselves before the altars. The same scenes were to be seen in small towns and villages, so that the mountains and the fields seemed to resound alike the voice of men who were crying to God.

“All musical instruments and love songs then ceased to be heard. The only music that prevailed, both in town and country, was that of the lugubrious voice of the penitent, whose mournful accents might have moved hearts of flint, and even the eyes of the obdurate sinner could not refrain from tears.

“Nor were women exempt from the general spirit of devotion we mention, for not only those among the common people, but also matrons and young maidens of noble families would perform the same mortifications with modesty in their own rooms. Then those who were at enmity with one another became 89 again friends. Usurers and robbers hastened to restore their ill-gotten riches to their right owners. Others, who were contaminated with different crimes, confessed them with humility, and renounced their vanities. Gaols were opened, prisoners were delivered, and banished persons permitted to return to their native habitations. So many and so great works of sanctity and Christian charity, in short, were then performed by both men and women, that it seemed as if an universal apprehension had seized mankind, that the divine power was preparing either to consume them by fire or destroy them by shaking the earth, or some other of those means which divine Justice knows how to employ for avenging crimes.

“Such a sudden repentance which had diffused itself all other Italy and even reached other countries, not only the unlearned, but wise persons also admired. They wondered whence such a vehement fervour of piety could have proceeded; especially since such public penances and ceremonies had been unheard of in former times, had not been approved by the sovereign Pontiff, who was then residing at Anagni, nor recommended by any preacher or person of eminence, but had taken their origin among simple persons, whose example both learned and unlearned had alike followed.”

The ceremonies we mention were soon imitated, as the same author remarks, by the other nations of Italy; though they at first met with opposition in 90 several places from divers Princes or Governments in that country. Pope Alexander the Fourth, for instance, who had fixed his See at Anagni, refused at first, as hath been above said, to give his sanction to them; and Clement VI., who had been Archbishop of Sens, in France, in subsequent times condemned these public flagellations by a Bull for that purpose (A. D. 1349). Manfredus, likewise, who was Master of Sicily and Apulia, and Palavicinus, Marquis of Cremona, Brescia and Milan, prohibited the same processions in the countries under their dominion; though, on the other hand, many Princes as well as popes countenanced them, either in the same times or afterwards.

This spirit of public penance and devotion was in time communicated to other countries; it even reached so far as Greece, as we are informed by Nicephorus Gregoras, who wrote in the year 1361. Attempts were likewise made to introduce ceremonies of the same kind into Poland, as Baronius says in his Annals, but they were at first prohibited; nor did they meet at the same period with more encouragement in Bohemia, as Debravius relates in his History of that country.

In Germany, however, the sect or fraternity of the flagellants, proved more successful. We find a very full account of the first flagellating processions that were made in that country in the year 1349, (a time during which the plague was raging there), in the 91 Chronicle of Albert of Strasbourg, who lived during that period.

“As the plague,” says the above author, “was beginning to make its appearance, people then began in Germany to flagellate themselves in public processions. Two hundred came at one time from the country of Schwaben to Spira, having a principal leader at their head, besides two subordinate ones, to whose commands they paid implicit obedience. When they had passed the Rhine at one o’clock in the afternoon, crowds of people ran to see them. They then drew a circular line on the ground, within which they placed themselves. There they stripped off their clothes and only kept upon themselves a kind of short shirt, which served them instead of breeches, and reached from the waist down to their heels; this done, they placed themselves on the above circular line, and began to walk one after another round it, with their arms stretched in the shape of a cross, thus forming among themselves a kind of procession. Having continued this procession a little while, they prostrated themselves on the ground, and afterwards rose one after another in a regular manner, every one of them as he got up, giving a stroke with his scourge to the next, who in his turn likewise rose and served the following one in the same manner. They then began disciplining themselves with their scourges, which were armed with knots and four iron points, all the while singing the usual psalm of the invocation 92 of our Lord, and other psalms; three of them were placed in the middle of the ring, who, with a sonorous voice, regulated the chant of the others, and disciplined themselves in the same manner. This having continued for some time, they ceased their discipline; and then, at a certain signal that was given them, prostrated themselves on their knees, with their arms stretched, and threw themselves flat on the ground, groaning and sobbing. They then rose and heard an admonition from their leader, who exhorted them to implore the mercy of God on the people, on both their benefactors and enemies, and on the souls in Purgatory; then they placed themselves again upon their knees with their hands lifted towards heaven, performed the ceremonies as before, and disciplined themselves anew as they walked round. This done, they put on their clothes again, and those who had been left to take care of the clothes and the luggage came forward and went through the same ceremonies as the former had done. They had among them priests, and noble as well as ignoble persons, and men conversant with letters.

“When the disciplines were concluded one of the brotherhood rose, and with a loud voice read a letter, which he pretended had been brought by an angel to St. Peter’s Church, in Jerusalem; the angel declared in it that Jesus Christ was offended at the wickedness of the age, several instances of which were mentioned, such as the violation of the Lord’s day, blasphemy, 93 usury, adultery, and neglect with respect to fasting on Fridays. To this the man who read the letter added, that Jesus Christ’s forgiveness having been implored by the Holy Virgin and the Angels, he had made answer that in order to obtain mercy, sinners ought to live exiled from their country for thirty-four days, disciplining themselves during that time.

“The inhabitants of the town of Spira were moved with so much compassion for these penitents, that they invited every one of them to their houses; they however refused to receive alms severally, and only accepted what was given to their Society in general, in order to buy twisted wax-candles and banners. These banners were of silk, painted of a purple colour; they carried them in their processions, which they performed twice every day. They never spoke to women, and refused to sleep upon feather beds. they wore crosses upon their coats and hats, behind and before, and had their scourges hanging at their waist.

“About an hundred men in the town of Spira enlisted in their Society, and about a thousand at Strasburg, who promised obedience to the Superiors for the time above mentioned. They admitted nobody but who engaged to observe all the above rules during that time, who could spend at least fourpence a day, lest he should be obliged to beg, and who declared that he had confessed his sins, forgiven his enemies, and obtained the consent of his wife. They 94 divided at Strasburg, one part went up and another part down the country, their Superiors having likewise divided. The latter directed the new brothers from Strasburg not to discipline themselves too harshly in the beginning; and multitudes of people flocked from the country up and down the Rhine, as well as the inland country, in order to see them. After they had left Spira, about two hundred boys twelve years old, entered into an association together, and disciplined themselves in pubic.”

Flagellating processions and solemnities of the same kind were likewise introduced into France, where they met at first with but indifferent success, and even several divines opposed them. The most remarkable among them was John Gerson, a celebrated theologian and Chancellor of the University of Paris, who purposely wrote a treatise against the ceremonies in question, in which he particularly condemned the cruelty and great effusion of blood with which these disciplines were performed. “It is equally unlawful,” Gerson asserted, “for a man to draw so much blood from his own body, unless it be for medical reasons, as it would be for him to castrate or otherwise mutilate himself. Else it might upon the same principle be advanced, that a man may brand himself with red-hot irons; a thing which nobody hath, as yet, either pretended to say or granted, unless it be false Christians and idolaters, such as are to be found in India, who think it a matter of duty for one to be baptized through fire.”

95Under King Henry the Third, however, the processions of disciplinants found much favour in France; and the King we mention, a weak and bigoted Prince, not only encouraged these ceremonies by his words, but even went so far as to enlist himself in a Fraternity of Flagellants. The example thus given by the King, procured a great number of associates to the brotherhood; and several Fraternities were formed at Court, which were distinguished by different colours, and composed of a number of men of the first families in the kingdom. These processions thus formed of the King and his noble train of disciplinants, all equipped like flagellants, frequently made their appearance in the public streets of Paris, going from one church to another; and in one of those naked processions the Cardinal of Lorraine, who had joined in it, caught such a cold, it being about Christmas time, that he died a few days afterwards. The following is the account to be found on that subject in President J. A. Thou’s “History of his Own Times.”

“While the civil war was thus carrying on, scenes of quite a different kind were to be seen at Court, where the King who was naturally of a religious temper, and fond of ceremonies unknown to antiquity, and who had formerly had an opportunity to indulge this fancy in a country subjected to the Pope’s dominion, would frequently join in the processions which masked men used to perform on the days before Christmas.

96“For more than an hundred years past a fondness for introducing new modes of worship into the established religion had prevailed; and a sect of men had risen, who, thinking it meritorious to manifest the compunction they felt for their offences by outward signs, would put on a sack-cloth in the same manner as it was ordered by the ancient law; and from a strained interpretation they gave of the passage in the Psalmist, ad flagella paratus sum, flagellated themselves in public, whence they were called by the name of Flagellants. John Gerson, the Chancellor of the University of Paris and the purest theologian of that age, wrote a book against them. Yet the holy Pontiffs, considering then that sect with more indulgence than the former ones had done, showed much countenance to it; so that multitudes of men all over Italy in these days enlist in it, as in a kind of a religious militia, thinking to obtain by that means forgiveness of their sins. Distinguished by different colours, blue, white, and black, in the same manner as the Green and Blue Factions, though proposing to themselves different objects, were formerly in Rome they likewise engrossed the attention of the public, and in several places gave rise to the warmest contentions.

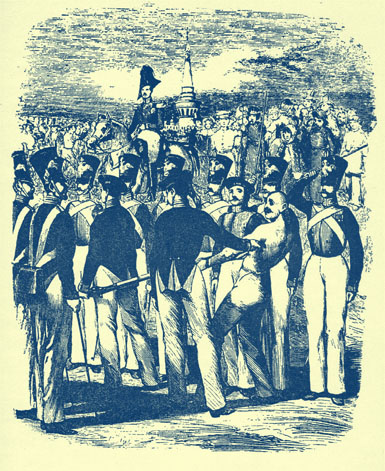

RUNNING THE GAUNTLET

A Punishment employed in the Russian Army.

“The introduction which was made of these ceremonies into France, where they had till then been almost unknown, forwarded the designs of certain ambitious persons; the contempt they brought on the 97 person of the King having weakened much the regal authority. While the King mixed thus with processions of flagellants, and the most distinguished among his courtiers followed his example, Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine, who was one of the party, was by the coldness of the evening thrown into a violent fever, attended with a most intense pain in his head; and a delirium as well as continual watchfulness having followed, he expired two days before Christmas.”

The historian we have just quoted says in another place, that the King was principally induced to perform the above superstitious processions by the solicitations of his confessor, Father Edmund Auger, who wrote a book on that subject, and of John Castelli, the Apostolic Nuncio in France; and that the weak compliance shown to him on that occasion by the Chancellor Birague, and the Keeper of the Seals, Chiverny, encouraged him much to pursue his plan in that respect, notwithstanding the strong advices to the contrary that were given him by Christopher de Thou, President of the Parliament, and Pierre Brulart, President of the Chambre des Enquêtes.

As there was in those times a powerful party in France that opposed the Court, and even was frequently at open war with it, there was no want of men in Paris who found fault with the disciplining processions of the King. When they first made their appearance, some, as the above historian relates, laughed at them, while others exclaimed that they 98 were an insult both to God and man. Even preachers joined in the party and pointed their sarcasms from the pulpit against those ceremonies.

The most petulant among these popular preachers was one Maurice Poncer, of the abbey of Melun, who, using expressions borrowed from a psalm, compared the King and his brother disciplinants, to men who would cover themselves with a wet sack-cloth to keep off the rain; he was at last banished off to his monastery. The example which the Court and the Metropolis had set, was followed in a number of country towns, where fraternities of flagellants were instituted; and among them particular mention is made of the brotherhood of the Blue Penitents, in the city of Bourges, on account of the sentence passed in the year 1601 by the Parliament of Paris, in consequence of a motion of Nicholas Servin, the King’s Advocate General, which expressly abolished it.

ONLINE NOTES

Froissart has this account in his History, p. 200;

This year of our Lord 1349, there came from Germany, persons who performed public penitencies by whipping themselves with scourges, having iron hooks, so that their backs and shoulders were torn: they chaunted also, in a piteous manner, canticles of the nativity and suffering of our Saviour, and could not, by their rules, remain in any town more than one night: they travelled in companies of more or less in number, and thus journeyed through the country performing their penitence for thirty-three days, being the number of years JESUS CHRIST remained on earth, and then returned to their own homes. These penitencies were thus performed, to intreat the Lord to restrain his anger, and withhold his vengeance: for, at this period, an epidemic malady ravaged the earth, and destroyed a third part of its inhabitants. They were chiefly done in those countries the most afflicted, whither scarcely any could travel, but were not long continued, as the church set itself against them. None of these companies entered France: for the king had strictly forbidden them by desire of the pope, who disapproved of such measures, by sound and sensible reasons, but which I shall pass over. All clerks or persons holding livings, that countenanced them, were excommunicated, and several were forced to go to Rome to purge themselves.

Thomas Johnes, footnoted this paragraph and blames the rise of the flagellants on the plague:

I refer my readers to the different chronicles of the times, for more particular information. Lord Hailes dates its ravages in 1349, and says; “The great pestilence, which had long desolated the continent, reached Scotland. The historians of all countries speak with horror of this pestilence. It took a wider range, and proved more destructive than any calamity of that nature known in the annals of mankind. Barnes, pp. 428 — 441, had collected the accounts given of this pestilence by many historians; and hence he has, unknowingly, furnished materials for a curious inquiry into the populousness of Europe in the fourteenth century.”

“The same cause which brought on this corruption of manners produced a new species of fanaticism. There appeared in Germany, England, and Flanders, numerous confraternities, of penitents, who, naked to the girdle, dirty and filthy to look, at, flogged themselves in the public squares, chaunting a ridiculous canticle. Underneath are two stanzas of their canticle, consisting of nineteen in the whole. It is entire in a chronicle belonging to M. Brequigny, which is the only one supposed to express it:

“Or avant, entre nous tuit frere,

Battons nos charoignes bien fort,

En remembrant la frand misere

De Dieu, et sa piteuse mort,

Qui fut pris de la gent amere,

Et venduz, et traiz à tort,

Et battu sa char vierge et claire;

On nom de ce, battons plus fort.

O Roiz des roiz, char precieuse,

Dieux Pere, Filz, Sains Esperis,

Vos saintisme char glorieuse,

Fut pendue en crois par Juis

Et la fut grief et doloreuse:

Quar vo douz saint sanc beneic

Fit la croix vermeille det hideuse,

Loons Dieu et battons nos pis.”

M. LEVESQUE, tom. i. pp. 530, 531.

Knighton also wrote about it, which was translated from the Latin by Dorothy Hughes in her book on this site, Illustrations of Chaucer's England, pp.192-193;

In the year 1349, about Michaelmas, more than six score men, natives, for the greater part, of Holland and Zeeland, came to London from Flanders. And twice a day, sometimes in the Church of St. Paul, sometimes in other places of the City, in sight of all the people, covered with a linen cloth from the thighs to the heels, the rest of the body being bare, and each wearing a cap marked before and behind with a red cross, and holding a scourge with three thongs having each a knot through which sharp points were fixed, went barefoot in procession one after another, scourging their bare and bleeding bodies. Four of them would sing in their own tongue, all the others making response, in the manner of litanies sung by Christians. Three times in their procession all together would fling themselves upon the ground, their hands outspread in the form of a cross, continually singing. And beginning with the last, one after another, as they lay, each in turn struck the man before him once with his flail; and so from one to another, each performed the same rite to the last. Then each resumed his usual garments, and still wearing their caps and holding their flails, they returned to their lodging. And it was said that they performed the same penance every evening.