From History of Flagellation Among Different Nations. New York: Medical Publishing Co., 1930: pp. 54-67.

THE holy founders of religious orders considered flagellations as being less useful in the convents of women than in those of men; and in the rules they have framed for them, they have accordingly ordered that kind of correction to be inflicted upon those whose bad conduct made it necessary.

This chastisement of flagellation, upon women who make a profession of a religious life, is no new thing in the world. It was the chastisement appropriated to the vestals, in ancient Rome; and we find in the historians, that when faults had been committed by them in the discharge of their functions, it was commonly inflicted upon them by the hands of the priests, or sometimes of the great priest himself.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus relates, that the virgin Urbinia was lashed by the priests, and led in procession through the town.

The high priest, Publius Licinius, ordered, as we read in Valerius Maximus, “that a certain vestal who had suffered the sacred fire to be extinguished, should be lashed and dismissed.”

Julius likewise relates, “that the fire in the Temple of Vesta having happened to be extinguished, the virgin was whipped by the high priest, M. Æmilus, 55 and promised never to offend again in the same manner.” And Festus says in his book, that “whenever the fire of Vesta came to be extinguished, the virgins were lashed by the great priest.”

Severities of the like kind have been deemed necessary to be introduced into the convents of modern nuns, by the holy fathers who have framed religious rules for them.

In that very ancient rule for the conduct of nuns, which is contained in epistle cix. of St. Augustin, the mortification of discipline is prescribed to the prioress herself. “Let her,” it is said in the above rule, “be ever ready to receive discipline, but never impose it but with fear.”*

Cesarius, Archbishop of Arles, in the rule framed by him which is mentioned with praise by several ancient authors, such as Genadius and Gregory of Tours, prescribes the discipline of flagellation to be inflicted upon nuns who have been guilty of faults; and enters, besides, into several particulars about the propriety as well as usefulness of this method of correction. “It is just,” he says, “that such as have violated the institutions contained in the rule should receive an adequate discipline; it is fit that in them should be accomplished what the Holy Ghost has in former times prescribed through Solomon: He who loves his child, frequently applies the rod to it.”

St. Donat, Archbishop of Bezancon, in the rule he 56 has framed for nuns, has expressed the same paternal disposition towards them as Archbishop Cesarius has done: he recommends flagellation as an excellent methods of mending the morals of such of them as are wickedly inclined, or careless in performing their religious duties; and he determines the different kinds of faults for which the above correction ought to be bestowed upon them, a well as the number of the blows that are to be inflicted. The above rule of St. Donat has been mentioned with much praise by the Monk Jonas, in his account of the life of St. Columbanus, which the venerable Bede has inserted in the third volume of his works.

In that rule, commonly called the rule of a father, which St. Benedict, Bishop of Aniana, in his book on the concordance of rules, and Smaragdus in his commentaries on the rule of St. Benedict, have both mentioned, provisions of the same kind as those are made for the correction of nuns. “If a sister,” it is said in that rule, “that has been several times admonished, will not mend her conduct, let her be excommunicated for a while in proportion to the degree of her fault; if this kind of correction proves useless, let her then be chastised by stripes.”

Striking a sister has likewise been looked upon as an offence of a grievous kind; and St. Aurelian, in the rule he has framed for nuns, orders a discipline to be inflicted on such as have been guilty of it.

To the above regulations, Archbishop Cesarius has 57 added another, which is, that the corrections ought for the sake of example to be inflicted in the presence of all the sisters. “Let also the discipline be bestowed upon them in the presence of the congregation, conformable to the precepts of the apostle. Confute sinners in the presence of all.”

It is expressly said of St. Pardulph, a Benedictine Monk and Abbot, who lived during the time of Charles Martel, about the year 737, that he used in Lent-time to strip himself stark naked, and order one of his disciples to lash him. The fact is related in the life of that saint, formerly written by an author who lived about the same time; and it was, two hundred years afterwards, put into more elegant language by Yvus, Prior of Clugny, at the desire of the monks of St. Martial, in the town of Limoges. Hugh Menard, a Benedictine father, and a very learned man in all that relates to ecclesiastical antiquities, has inserted part of it in his book, intitled, “Observations on the Benedictine Martyrology.” The following is the passage in St. Pardulph’s Life, which is here alluded to. “St. Pardulph seldom went out of his cell; whenever sickness obliged him to bathe, he would previously make incisions in his own skin. During Lent he used to strip himself entirely naked, and ordered one of his disciples to lash him with rods.”

St. William, Duke of Aquitain, who lived in the 58 time of Charlemagne, that is about the year 800, and many years before Cardinal Damian; is said to have also used flagellations, a means of voluntary penance. Arduinus, the writer of the holy duke’s life, and a contemporary writer, says, that “it was commonly reported that the duke did frequently, for the love of Christ, cause himself to be whipped, and that he then was alone with the person who assisted him.” Haeftenus, Superior of the Monastery of Affigen, relates the same fact, and says that the Duke of Aquitain “took a great delight in sleeping upon a hard bed, and that he moreover lashed himself with a scourge.” Hugh Menard, the learned Benedictine just now mentioned, has adopted the testimony of Arduinus, and upon that writer’s authority inserted the above fact in his “Observations on the Benedictine Martyrology.”

Other persons, who lived before the time of Cardinal Damian, are also mentioned by different writers as having practised voluntary flagellations. Gaulbertus, Abbot of Pontoise, who lived about the year 900, upon a certain occasion, “severely flagellated himself (as M. Du Cange relates in his glossary) with a scourge made of knotted thongs.” And the above-mentioned Haefetenus, Prior of Affigen, has advanced that the same practice was followed by St. Romuald, who lived about the same time as Gualbertus, and by the monks of the Camaldolian order, who were settled in Sitria.

59Another early instance of voluntary flagellations occurs in the life of Guy, Abbot of Pomposa. Heribert, it is said, Archbishop of Ravenna, formed the design of pulling down the Monastery of Pomposa; and this piece of news caused both Abbot Guy and his monks “to lock themselves up in the capitular house, and to lash themselves every day, for several days, with rods.” Abbot Guy was born in the year 956; and he was made Abbot of Pomposa in the year 998, in which capacity he continued forty-eight years.

All the facts above related were anterior in the year 1056, the time at which Peter Damian de Honestis was a raised to the Cardinalship by Pope Stephen IX; and it is evident from them, that the practice of voluntarily flagellating oneself as a penance for committed sins, had been adopted before the period in question, though it cannot be said to have been then universally prevalent; at least only a few instances of it have been left us by the writers of those times. But at the era we mention, this pious mode of self correction, owing to the public and zealous patronage with which the above Cardinal favoured it, acquired a vast degree of credit and grew into universal esteem; and then it was that persons of religious dispositions were everywhere seen to arm themselves with whips, rods, thongs, and besoms, and lacerate their own hides, in order to draw upon themselves the favour of heaven.

We are informed of this fact by the learned Cardinal 60 Baronius, in his Ecclesiastical Annals. “At that time,” he says, “the laudable usage of the faithful of beating themselves with whips made for that purpose, though Peter Damian may not be said to have been the author of it, was much promoted by him in the christian church; in which he followed the example of the blessed Dominic the Cuirassed, a holy hermit, who has subjected himself to his authority.”

The same Cardinal Damian has moreover left numerous accounts of voluntary flagellations practiced by certain holy men of his time; but these are surely more apt to create our admiration, than to excite us to imitate them. Indeed the flagellations he mentions cannot be proposed to the faithful as examples they ought to follow; and they were executed with such dreadful severity, as makes it impossible for the most vigorous men to go through the like, without a kind of miracle.

In the Life of the Monk of St. Rodolph, who was afterwards made Bishop Eugubio, the Cardinal relates, “That this holy man would often impose upon himself a penance of an hundred years, and that he performed it in twenty days, by the strenuous application of a broom, without neglecting the other common methods used in doing penance. Every day, being shut up in his cell, he recited the whole psalter (or book of psalms) at least one time when he could not two, being all the while armed with a 61 besom in each hand, with which he incessantly lashed himself.”

The account which the Cardinal has left of Dominic, surnamed the Cuirassed, is not less wonderful. “His constant practice,” he says, “is, after stripping himself naked, to fill both his hands with rods and then vigorously flagellate himself; this he does in his times of relaxation. But during Lent-time, or when he really means to mortify himself, he frequently undertakes the hundred years’ penance; and then he every day recites the psalter at least three times over, all the while flogging himself with besoms.”

Cardinal Damian then proceeds to relate the manner in which the same Dominic informed him he performed the hundred years’ penance. “A man,” said he, “may depend he has accomplished it, when he has flagellated himself during the whole time the psalter was sung twenty times over.” The same author adds several circumstances which make the penances performed by the holy man appear in a still more admirable light. He, in the first place, was so dexterous as to be able to use both his hands at once, and thus laid on twice the number of lashes others could do who only used their right hand. In one instance, he fustigated himself during the time the whole book of psalms was sung twice over; on another occasion he did the same while it was sung eight times; and on another, while it was repeated 62 twelve times over; “which filled me with terror,” the Cardinal adds, “when I heard the fact.”

Cardinal Damian also relates of the same Dominic, the Cuirassed, that he at last changed his discipline of rods into that of leather thongs, which was still harsher; and that he had been able to accustom himself to that laborious exercise. Nay, so punctual was he in performing the duties he had imposed upon himself, that, “when he happened to go abroad (being an hermit) he carried his scourge in his bosom, to the end that wherever he happened to spend the night, he might lose no time, and flog himself with the same regularity as usual. If the place in which he had taken his refuge for the night did not allow him to strip entirely, and fustigate himself from head to foot, he at least would severely beat his legs and head.”

Even sovereigns and great men, in the times we speak of, adopted for themselves the practice of voluntary flagellation.

The Emperor Henry, who lived about the year 1070, “never ventured (if we may credit Reginard’s account) to put on his imperial robes, before he had obtained the permission of a priest for that purpose, and had deserved it by confession and discipline.”

William of Nangis, in the life of St. Lewis, in the life of St. Lewis, King of France, which he has written, relates that that prince, after he had made his confession, constantly 63 received discipline from his confessor. To this the same author adds the following curious account: “I ought not to omit to say, concerning the confessor the king had before Geoffrey de Belloloco, and who belonged to the order of the Predicant Friars, that used to inflict upon him hard and immoderate disciplines; which the king, whose skin was rather tender, had much ado to endure. This hardship, however, he never would speak of to this confessor; but after his death, the mentioned the fact somewhat jocularly, though not without humility, to the new confessor.”

An instance of much the same nature with the facts above recited, is to be found in one of Osbertus’s books. A certain English count having contracted an unlawful marriage with one of his near relations, not only parted afterwards with her, but requested besides to be disciplined in the presence of St. Dunstan, and of the general assembly of the clergy. “Terrified,” says Osbertus, “by the greatness of his offence, his obstinacy ceased; and after having renounced his unlawful wedlock, he imposed upon himself the task of penitence. As Dunstan was then presiding over a meeting of the clergy of the kingdom, which was holden according to custom, the count came into the middle of the assembly, bare-footed, clothed with wool, and carrying rods in his hands; and threw himself, groaning and weeping, at the feet of St. Dunstan. This instance of piety moved the whole assembly, and Dunstan more than 64 the rest. However, as his wish was thoroughly to reconcile the man with God, he preserved an appearance of severity in his looks, suitable to the occasion, and for a whole hour persevered in denying his request: when, at last, all the prelates having joined in the entreaties of the count, St. Dunstan granted him the indulgence he was suing for.” From the above fact, we might conclude that flagellations voluntarily submitted to, had become, even before the era of Cardinal Damian, a settled method of atoning for past sins, since St. Dunstan lived about an hundred years before the Cardinal; that is about the year 950.

Instances of sovereigns and great men requesting to undergo flagellations, must have been pretty common in the days we mention, frequent allusions being made to it in old books; among others in that old French romance, entitled, The History of the Round Table and the Feats of the Knights, Launcelot du Lac. King Arthur is supposed in it, to have summoned all the bishops who were in his army, to his chapel; and there to have requested of them, a correction of the same king as that undergone by the count mentioned by Osbertus.

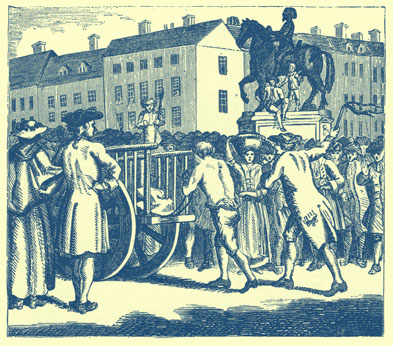

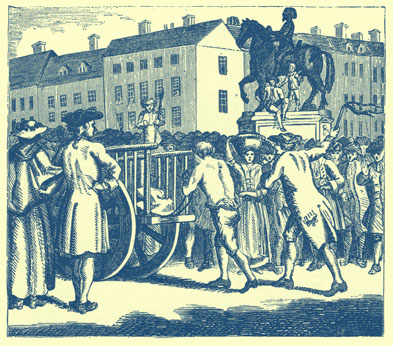

STROUD, THE NOTORIOUS CHEAT, WHIPPED AT THE CART’S-TAIL FROM

CHARING CROSS TO WHITEHALL.

From the times we mention, we find numerous proofs of self-flagellation being used in convents: and indeed it would have been a very extraordinary circumstance if, while the persons above-named adopted that practice, monks had rejected it. In the fifty-third 65 article of the statutes of the Abbey of Cluny, which were collected by Peter Maurice, surnamed the Venerable, who was raised to the dignity of Abbot in the year 1122, the following account is given. “It was ordained (it is said in that Article) that that part of the Monastery which is on the left, beyond the left Choir, should remain open to no strange persons, whether Ecclesiastical or Lay, as it was formerly, and nobody admitted into it except the Monks. This was thus settled, because the Brothers had no place, except the old Church of St. Peter, in which they could practice such holy and secret exercises as are usual with religious persons; they therefore claimed the use of the above new part of the Church, both for the night and the day, that they might constantly therein make offerings of the perfumes of their prayers to God, supplicate their Creator by frequent acts of repentance and genuflexions, and mortify their bodies by often inflicting upon themselves three flagellations, either as penances for their sins or as an increase of their merit.”

The practice in question gained so much credit, about those times, in Monasteries, that St. Bruno, who, a few years after the death of Cardinal Damian, founded the Carthusian Order, thought it necessary to restrain his Monks in that respect; not unlikely, perhaps, with the view to check the pride which they used to derive from such exercises. In one of the statutes laid by that Saint, which Prior Guiges has 66 collected, the following regulation is contained. “In regard to such disciplines, watchings, and other religious exercises as are not expressly enjoined by our Institution, let nobody among us perform them, except it be by the Prior’s permission.”

So much were flagellations grown into fashion in the days we mention, such attractions did they even seem to possess, that ladies of high rank would also enlist among the above-mentioned Whippers, and almost vied with Dominic the Cuirassed, Rodolph de Eugubio, St. Anthelm, and Abbot Poppo, in regard to the regularity with which they performed such meritorious exercises. Among those ladies, particular mention is made of St. Maria of Ognia, of St. Hardwigge, Duchess of Poland, of St. Hildegarde, and above all of the Widow Cechald, who lived in the very times of Cardinal Damian, and performed wonderful feats in the same career, as we are informed by St. Antonius, upon the authority of Cardinal Damian himself. “Not only Men, but also Women of noble birth eagerly sought after that kind of purgatory; and the Widow of Cechaldus, a woman of great birth and dignity, gave an account, that in consequence of an obligation she had previously imposed upon herself, she had gone through the hundred years’ penance, three thousand lashes being the number allotted for every year.”

67The Widow Cechald, in her own account of the wonderful penance she performed after the example of Dominic the Cuirassed, has neglected to inform us in what manner she performed it, and whether she imitated that holy Man in every respect, and used, for instance, both her hands at once in the operation. Be it as it may, three hundred thousand lashes, the total amount of the hundred years’ penance she went through, were certainly a very hard penance. However, as we are not to doubt either the account which the above Widow gave in that respect, or the declaration Cardinal Damian made after her, the wonder is to be explained another way, and perhaps by the nature of the instruments she made use of: they possibly were of much the same kind as those used by a certain lady, who was likewise much celebrated on account of the frequent disciplines she bestowed upon herself, and who was at last found out to use no other weapons for performing them than a bunch of feathers, or, as others have said, a fox’s tail.

* NUM. xii. “Disciplinam lubens habeat, metuens imporat.”