Chinon

Click on the footnote number or mark (*, §, †, etc.) and you will jump to it, then click that footnote number or mark again, and you will jump back to where you were in the text [That line will be at the top of the screen].

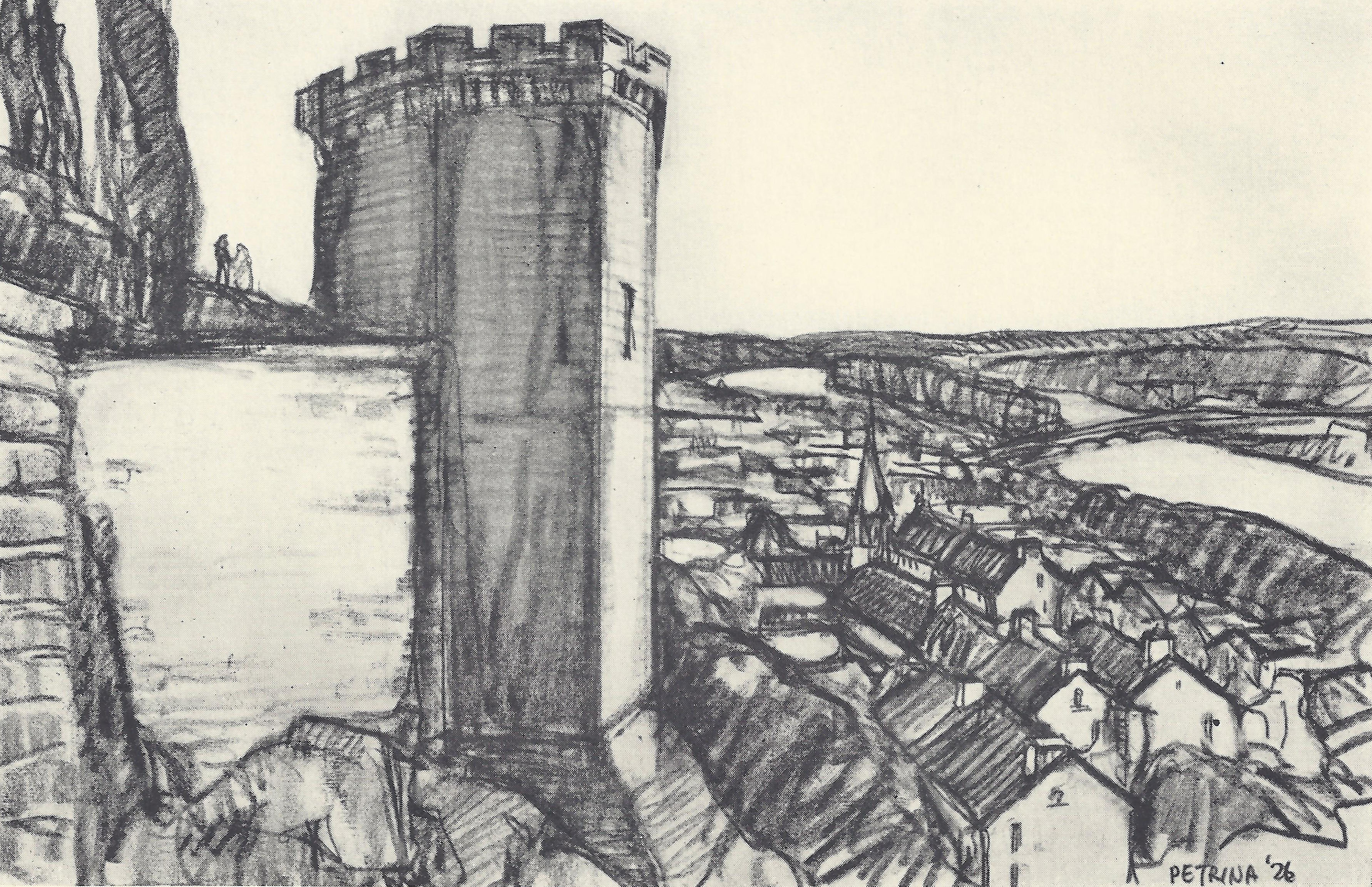

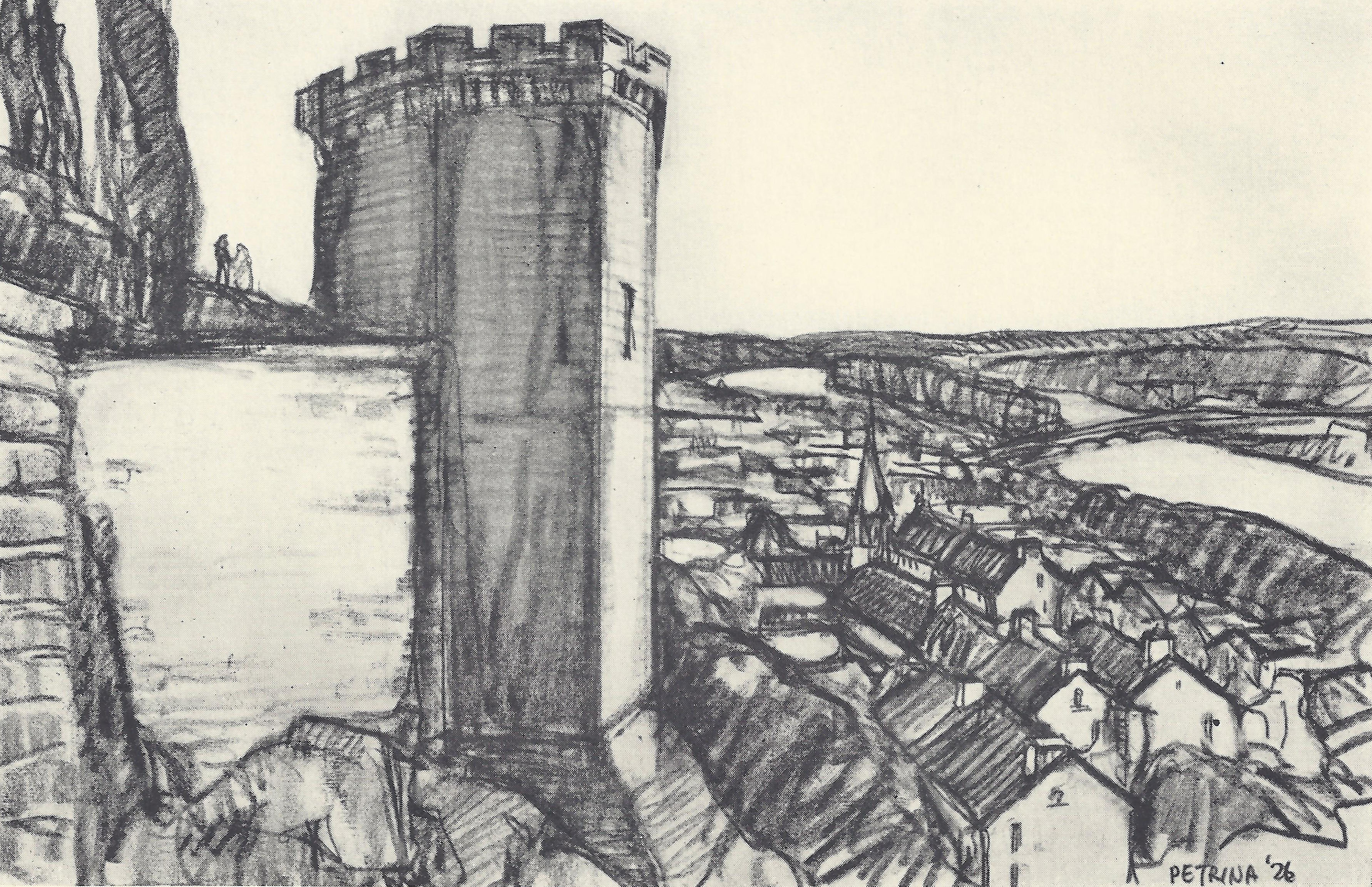

From Trails of the Troubadours, by Ramon de Loi [pseud. Raymond de Loy Jameson], Illustrated by Giovanni Petrina, New York: The Century Co., 1926; pp. 185-206.

TRAILS OF THE TROUBADOURS

by Raimon de Loi

Chinon

KING HENRY II of England, like Humpty-Dumpty, to whom he bore a striking resemblance — both were oval in body, tending toward the round — had a great fall; and since his and Humpty’s falls were from the heights, none of his horses and none of his men could ever put him together again. When he fell he thought it was God taking vengeance on him for his various misdeeds and misdemeanors. In this thought he failed to do justice to his demoniac wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, said to have been born of the devil, sometime queen of the troubadours, the old woman of the tower, who, too weak herself to wreak her spite on her husband, had borne from her body a pack of angry, proud, noisy, suspicious, and quarrelsome sons, who, as Henry himself said, pecked at his heart like young eaglets at raw meat. Finally the old heart broke, and Henry, breathing defiance to the God of the Christians, turned his face to the wall.

Henry was the superman of the age of troubadours, and his successes were phenomenal and characteristic of his time. While he was still a young man, he succeeded where his father had failed in seducing Eleanor of Aquitaine, the wealthy wife of King Louis of France. She threw her wealth in his lap, a toy for him to play with, a stake for him to throw on the table in his big game which [188] finally brought him the crown of England. He was victorious in his struggles with his relatives, the barons of France, England, and Normandy; he was victorious in his struggles with those other barons who were not his relatives; he was successful in his struggles with two French kings, and with the church at Rome. Where other men would have lost a battle, he won it; where other men would have wasted weeks besieging a city, he took it in a single night; where other men would have been betrayed, he caught the traitor in the act. He launched defiance at the church and at God. The struggle was bitter, and for a time, when Thomas Becket was murdered, the world thought that Henry the superman was to be defeated; but from this too he drew new strength and lived to see the day when the great lords spiritual came begging at his door and he sent them about their business with a cynical oath. He was even successful in that more bitter struggle from which no man emerges unscathed, the struggle with his wife, the demoniac woman from Aquitaine, said to have been born of the devil but certainly the daughter of a nun raped from a convent. But this superman was superior to his fellows only in having more intensely than they the great human virtues and vices. He was shrewd enough to make strength out of his weaknesses. He was more concerned, said a contemporary, about a dead soldier than a living knight; and this, in a century of universal warfare and slaughter, was a great weakness. Partly because of his sympathy with his soldiers, and partly because, like Mr. Shaw, he was a good housekeeper and disliked to see things wasted, he avoided battle whenever he could make diplomacy or bribery do the work. [189] Both he and his grandfather, Henry I, realized very clearly that a bribed enemy is worth a thousand dead followers.

Henry II was the fool of nature. He began life as a man. At an age when our youths are being exposed to courses of lectures carefully arranged to “teach a moral lesson and at the same time maintain the student’s interest,” Henry had blossomed into the superman of Europe. It was only after he had been a superman that he achieved the final dignity of being human. It was as a human being that Henry suffered the terrible humiliation at Le Mans and Gisors and defeat on the field of Colombières near Tours. It was the human being sick unto death that was carried on its last ride from Colombières to Chinon and thence to the grave whose open jaws devoured him at Fontevrault. None of the world about him understood the reason for his fall; and none, save perhaps wizened old Eleanor watching events from her tower, could realize that his defeat was more spectacular than his success. But when his sons betrayed him, when one after the other they mocked him and made war on him, when they permitted their archers to shoot at him while he stood in military parley with them before the walls of the cities they had stolen from him — when this treasure of affection made him the fool of the world, Henry’s life became ashes, and his body returned to the dust.

The fat old king was lonely. He sat in his château at Le Mans overlooking the bright river and the clean countryside [190] of Maine while messengers, one after the other, brought word of the approach of his enemies, closer and closer, under the leadership of Philip of France and Henry’s troubadour son, Richard the Lion-Heart. He might have done much for Richard had Richard not been his wife’s darling and therefore his enemy. . . . Again and again he had made overtures of peace and friendship to Richard. Again and again these overtures had been rejected. The fat old king was lonely. He limped up and down the walls of his castle. A June sunset was upon him. . . .

King Henry in his glorious youth, when every castle fell before him and the world trembled at his step, made merry with Thomas à Becket, the young churchman. Becket had taken orders, but only the first orders. He was still a free man, free as a bird in his actions, swift as a hawk in his thought. He became a faithful falcon to the king. Some chroniclers say that Becket’s father was Gilbert, a Saxon knight, and that his mother was a Saracen woman whom Gilbert had seduced while on the Crusades. She knew only two words of English; one of them was “London,” and the other was “Gilbert.” She followed him home from the Crusades and ran through the streets of London calling his name and ultimately found him. Thomas had studied at Bologna and had been a student of a student of Abelard’s. He made himself the king’s man and became the king’s chancellor. With a crowd of poets and pimps and wild women the young king would often descend on Becket in his sumptuous palace in London. He would sit on the [191] table while Becket finished his supper, and together they would plan wild parties.

Then Becket was made archbishop of Canterbury and as such the most powerful lord of England. Henry might subdue his independent barons and bend them to his will, but the primate, richer and more powerful in his own right than any baron, had as his support the great moral force of the church at Rome. The primate could not be subdued. The strife was long and bitter. The king’s fury raged more fierce at each new impertinence of the archbishop; the archbishop’s obduracy gleamed the brighter with each counter-move of the king. Becket was exiled from England. After seven years an apparent reconciliation was effected, and Thomas returned to Canterbury. His first official act was to excommunicate all the prelates, bishops, and clerks who had been friendly to the king. Then he returned to his palace, and since it was Christmas day and Thursday he ate meat like all the rest of the world in great high spirits.

Henry received word of these excommunications when he was at Avranches on December 29. The king cried: “If all my friends have been excommunicated, by God’s eyes, I’m excommunicated too! What a pack of fools and cowards I have nourished in my house, that not a one of them will avenge me of this one upstart clerk!” Four of his knights rid him of the upstart clerk, and England had another martyr and Henry a new difficulty. Henry shut himself in his room and for three days refused to eat or see visitors. When the pope heard the news he went into deep mourning. All the barons in England who had been waiting for the king to make a false step suddenly discovered that [192] they were true sons of the church and that Henry was their legitimate enemy. Thomas, the bon vivant and the obdurate protector of the church’s temporal interests, became a saint. He had sought martyrdom, and he had found it.

The old king paced the wall of Le Mans at night waiting for the knot of his enemies to tighten around him and shear from him his earthly power and humiliate him before the world. He thought of many things. He never forgot a friend and never forgave an enemy. Thomas had been both friend and enemy. Henry had been responsible for the death of Thomas; and yet, though he had caused that death, he had not intended it. He had done penance both as a king and as a private person. As a king he took oaths and made promises and gave large gifts of money to Templars. His private penance he performed three years later when he returned to England.

He made a pilgrimage to Canterbury. As he came in sight of the cathedral church he dismounted, and, in bare feet, forbidding all present to do him honor or treat him as though he differed in any way from a private pilgrim, he walked to the church. At the steps where Thomas fell, he dropped to his keens, kissed the spot, and wept. Then he came to the tomb of the saint. Here he lay for a long time weeping and praying. He made formal confession of his sins and returned all its rights to the see of Canterbury. All the churchmen present were invited to punish him. He removed his upper garments, and each priest gave him five blows with the rod and each monk three blows. He fasted [193] all that night, and the next morning before he left for London was given, as a sign of reconciliation, a drink of holy water in which some of the saint’s blood had been mixed. That he survived was a miracle of less importance to the medieval mind than the immediate arrival of news that the army of Scotland had been defeated and that the Scottish king, one of Henry’s most persistent enemies, had been captured. He, the citizen of England, had purged his soul; and Thomas the saint had brought a measure of success to Henry the king.

Thomas had gained a sainthood, and Henry had dreamed of an empire rivaling that of Rome. His lands were too vast for him to handle alone, but he had sons. To Richard, who was popularly believed to have the lion’s heart, he gave the lion’s share, Aquitaine. To John he gave Brittany; and Henry, his oldest son, he made partner in the rule of England. There were two kings: Henry the father, the old king; and Henry the son, the young king. “When I alone had rule of my kingdom,” he said, “I let nothing go of my rights; and now that many are joined in the government of my lands, it were a shame that any part of them were lost.” The barons, who hated the old king for conquering them, flocked to the court of the young; the wife, who hated her husband for subduing her, spurred the son to revolt; Philip, the king of France, who envied Henry his lands and power, invited the son to share in his pleasures, ate with him at the same table, slept with him in the same bed. . . .

[194]The day came when Richard refused to recognize the rights of his elder brother and when Bertrand de Born rode south breathing hope of death and damnation toward Richard and the old king. A war was fought between the two brothers. The old king watched cynically from London. Then to preserve his kingdom he threw his forces with Richard. Henry and Bertrand the troubadour grew desperate. They robbed monasteries and pillaged nunneries. After burning a castle a few miles south of Bertrand’s castle, Hautefort, the young king was seized with dysentery. He sent a message imploring his father to come to his bedside and grant forgiveness. Henry, fearing treachery, as well he might, since he had become now somewhat aware of the temper of his offspring, refused. The young king died in sackcloth on a bed of ashes repenting of his sins. Henry mourned for him as David for Absalom.

Richard was now the heir apparent and with his father marched through Aquitaine and Touraine punishing the rebellious vassals. Hautefort, Bertrand de Born’s castle, was taken after stubborn resistance. Bertrand was condemned to death. Dante a hundred years later thought that Bertrand had been the chief cause of the rebellion. He was brought before the king to show cause why the sentence of death should not be imposed upon him.

The king said: “Bertrand, Bertrand, thou hast always boasted that thou hadst never need of more than half of thy intelligence. It seems to me that to-day thou are in great need of all of it.”

“Sire,” said Bertrand, “what I have boasted is true, and it is still true to-day.”

[195]But the king said to him, “Indeed it seems to me that to-day thou hast lost it all.”

“Indeed, Sire,” replied the poet, “to-day I have none left.”

“And how is that?” asked the king.

“Sire,” replied Bertrand, “on the day that the valiant king, thy son, died, I lost my sense, my knowledge, my reason altogether.” The king when he heard Bertrand speak thus of his son and when he saw Bertrand in tears, felt his heart contract so powerfully that he fainted.

When he had recovered, he cried weeping: “Bertrand, Bertrand, thou wast right to lose thy reason in the cause of my son, for there was never a man in the world whom he loved more dearly than thee. For love of him, I will not only grant thee thy life and return to thee thy goods and thy castle, I will add my love and my good graces and five hundred marks of silver for the damages which thou hast suffered.”

The fat king paced the walls of Le Mans at the hour before dawn. The armies from Tours had advanced still further. A village just outside of the town was being burned. He must decide what was to be done, whether he should capitulate with his enemies and betray the city of his birth, or whether with his seven hundred fighting-men he should make a last and desperate stand. Perhaps he must think of moving, of flight. He had spent all of his life in movement. He had seldom stayed a week at a time in one place.

He had traveled over rough paths, through thickets, over hills, through marshland and fen, and always as the king traveled there followed behind him his disorderly court, [196] his army of secretaries, lawyers, knights in mail, barbers, hucksters, barons — each with dozens of retainers; an archbishop or two with their households, bishops and actors, judges, suitors, confectioners, “singers, dicers, gamblers, buffoons, wild women and what not.” The court was frequently forced to dine on stale black bread and old beer. It was forced to sleep in the open, in pigsties, in the mud.

If the king has proclaimed that he intends to stop late in any place, you may be sure that he will start early in the morning, and with his sudden haste destroy every one’s plans. It often happens that those who have let blood or taken purges are obliged at the hazard of their lives to follow. You will see men running about like mad, urging forward their packhorses, driving their wagons into one another, everything in confusion as if hell had broken loose. Whereas, if the king has given out that he will start early in the morning, he will certainly change his mind and you may be sure he will snore until noon. You will see the packhorses drooping under their loads, wagons waiting, drivers nodding, tradesmen fretting, all grumbling at one another. The men hurry to ask the liquor retailers and loose women who follow the court when the king will start for these are the people who know most of the secrets of the court.

At other times when the camp had composed itself to sleep, a sudden messenger would gallop in with despatches. The king would order the camp to be broken. Messengers would be sent ahead to announce the approach of the king, and the cortège would push forward through the muddy paths, the cart-loads of heavy state papers foundering and overturning, the horses struggling in the mire, the wagoners shouting, the courtiers swearing. . . . Then the king might [197] suddenly change his mind and stop for the night at a cabin in the woods where there was food and lodging for one man only. “And I believe, if I dare to say so, that he took delight in our distresses.” The knights, separated from their body-guards, would wander through the thickets in the darkness and fight to the death for the possession of some place of shelter which a dog would have disdained. “O Lord God Almighty,” the chronicler concludes, “turn and convert the heart of the king from this pestilent habit, that he may know himself to be but man, and that he may show a royal mercy and human compassion to those that are driven after him not by ambition but by necessity.”

My lord, the king [said another chronicler], is sub-rufus or pale red; his harness [armor, which he wore very tight in his youth, for he was vain] hath somewhat changed his color. Of middle stature he is so that among little men he seemeth not much, nor among long men seemeth he over little. His head is round as in token of great wit and of special high counsel the treasury. His head of curly hair when clipped square in the forehead showeth a lyonous visage, the nostrils even and comely according to all the other features. High vaulted feet, legs able to riding, broad bust, and long champion arms which telleth him to be strong, light, and hardy. In the toe of his foot, the nail groweth into the flesh and in harm to the foot overwaxeth. His hands, through their large size, showeth negligence, for he utterly leaveth the keeping of them; never, but when he beareth hawks, weareth he gloves. Each day at mass and counsel and other open needs of the realm, throughout the whole morning he standeth afoot, and yet when he eateth he never sitteth down. In one day he will if need be ride two or three journeys, and thus he hath oft circumvented the plots of his enemies. A huge lover of woods is he so that when he ceaseth war he haunteth places of hunting and hawking. . . . Homely and [198] short clothes weareth he. When once he loveth, scarcely will he ever hate; when once he hateth, scarcely ever receiveth he into grace. . . . When he may rest from worldly business, privily he occupieth himself with learning and reading and from his clerks he asketh questions . . . none is more honest than our king in speaking, ne in alms largesse. . . .

Thus he was in his prime, but now he was growing old. The square form had grown fat. The huge paunch had bowed the legs still more; the toe-nail had produced a habitual limp. The face was lined and worn. . . .

The situation Henry found himself in as he paced the château at Le Mans was no new situation. It was more critical for him now only because his sons happened to be leading the rebellious barons and because Philip of France was outguessing him and because he was growing old and weary of the struggle. He had dreamed of an empire for himself and his sons. Henry had died in rebellion against him. Geoffrey had said to a peacemaker: “Dost thou not know that it is our proper nature, planted in us by inheritance from our ancestors, that none of us should love other, but that ever brother should strive against brother and son against father? I would not that thou shouldst deprive us of our hereditary right nor vainly seek to rob us of our nature.” Richard was now the darling, not only of Henry’s spiteful wife Eleanor, but of Philip of France. The empire was broken.

He had hopes of Richard’s friendship after the [199] young king had died; but Richard soon showed his temper. “Give me my rights,” he said, “that I may arrange my kingdom.” On formal occasions, Richard, like his elder brother, insisted that Henry offer him the cup of wine. “It is fitting,” said Richard, “that the son of king should be served by the son of a duke.” There remained only one son who had not yet declared himself; it was young John Lackland. Henry spared no pains in his attempts to ingratiate himself with this young man. In John, Henry thought he might find an heir who would be loyal to his father’s interests and spare no pains in humbling his proud brothers, Richard and Geoffrey. At a conference with Philip of France, Henry proposed to transfer Richard’s lordship of Aquitaine to John. When he heard this, Richard was standing near Philip. Without a word he ungirt his sword and stretched out his hands in a dramatic gesture to do homage to the king of France for England’s continental possessions. The king’s horse reared. The court was in confusion. The knights drew their swords. Henry spurred his horse to the open and calling to two courtiers said: “Why should I revere Christ? Why should I think him worthy of honor who takes from me all honor in my lands and suffers me thus shamefully to be dishonored before that camp-follower Philip?”

His son Geoffrey had treated him as badly as Richard. During one of the frequent filial rebellions, Henry was parleying with Geoffrey in the market-place of Limoges in front of the château. Geoffrey’s archers aimed a shower of arrows at the king. One of the arrows pierced the ear of the king’s horse. Henry withdrew the arrow and presented [200] it to Geoffrey, saying, “Tell me, Geoffrey, what has thy unhappy father done to thee to deserve that thou, his son, shouldst make him a mark for thine archers?”

His lords were in revolt, and a great solitude fell upon him. Tours was in the hands of his enemies; Philip and Richard were approaching from the east; and the fat old king limped up and down the walls of Le Mans undecided whether he should flee northward or offer open battle. At dawn, the enemy set fire to a suburb to the west of Le Mans. With the enemy to the south and east and fire to the west, escape to the north would soon be cut off. Henry summoned his fighting-men and rode out, cut his way through the crowd at the bridge, and rode north. He spurred his horse up the small hill near the village now called La Bazogue and looked back on his burning city. He cursed God, and in his curses there was still the defiance of the superman. “The city which I have loved best on earth,” he cried, “the city in which I was born and bred, where my father lies buried, where is the body of St. Julian — this, Thou, O God, to the heaping up of my confusion, and to the increase of my shame, hast taken from me in this base manner! I therefore will requite as best I can: I will assuredly rob Thee too of the thing in me which Thou lovest best!”

The king and his party rode furiously by by-paths, through mud and mire, under the scorching sun. They burned their bridges behind them. Once Richard, spurring ahead of the pursuers, came up with the fleeing king. One of the king’s men raised his lance. Richard cried: “God’s feet, marshal, do not kill me. I have no hauberk.” [201]

The marshal struck his spear into Richard’s horse so that it fell dead. “No, I will not kill you. Let the devil kill you,” he shouted.

From the hill where Henry, looking back on his burning city, cursed God, I lose the trail. If there be local traditions, I have not been able to collect them. There are a thousand small paths and trails that may or may not have been made when Henry fled through the country. It is a land of gentle undulating hills and low valleys, each with its streamlet and its bit of marshland. The hills are pleasant, and the valleys are rich, but sometimes in the heat of June the mist rises from the marshy places, hot and unpleasant. That night Henry reached La Fresnay. He threw himself on his couch and refused to allow even Geoffrey the Bastard, the result of his adventure with Rosamond Clifford and the only issue of his body that remained faithful to him, to throw a cloak over his shoulders. He despatched messengers into Normandy to summon the remnants of his army, and once again, resolutely and with grave heart, turned his face toward his enemies and marched southward again to the city of Tours, his ancient heritage. All the castles on the route were held by his enemies. He could scarcely find a place to rest for the night.

On June 30, 1189, his army appeared before Tours, where the French king and Richard the Lion-Heart were encamped. But just as his army glimpsed the towers of the château rising beyond the river, Henry was seized with a sudden illness. Unable to meet the French king, he fell back down the river, under the vine-clad hills where the wine of Touraine grows into beauty and ripens into [202] richness. He was carried to the fortress of Saumur, where Richard his son, seven years earlier, in the first flush of the combat, had summoned a meeting of barons. The French king cried, “God has delivered mine enemy into my hands.” He commanded Henry to meet him on July 3 at Colombières, a field south of Tours.

Henry started for the meeting. He traveled back up the river as far as Ballan and the house of the Knights Templar. A terrible agony struck him. He leaned against the wall of the house, trembling in every nerve. His followers brought him a camp-bed. A messenger was despatched to Philip, and even Philip was compassionate. Not so Richard, the true son of his mother, the old woman of the tower, now tasting her revenge. “He feigns sickness,” said Richard, “to gain time”; and Philip sent word that Henry must at any cost meet him the next day, July 4, and hear the terms of peace.

Henry’s followers wished him to ignore the order, but he insisted on obeying. “Cost what it may,” he said, “I will grant whatever they ask to get them to depart. But this I tell you of a surety: if I can but live, I will heal my country from war and win my land back again.” On the fourth of July, through the sultry summer heat, he rode to Colombières,. On one side of the field, fresh and strong and in bright armor, surrounded by his arrogant lords, with Richard at his side, was the French king. A papal delegate and an English bishop, already suitors to the new rulers, were prominent among the French lords. The world had gathered at Colombières, to see the humiliation of fat old Henry, the man who for fifty years had ruled the world. [203] As he rode across the field, he clung to his horse as though in a last effort. His huge body was wasted, and the skin hung round him in folds. Philip, struck with sudden pity, called for a cloak to be laid on the field, that Henry might sit for the conference. Once more Henry burst into a rage. “I will not sit,” he cried; “even as I am, I will hear what you ask of me and why you cut short my lands.”

The heat was intolerable. The sky was liquid brass. High above the conferring monarchs were insubstantial fleecy heat-clouds. The poplar-trees along the north end of the field drooped. The very earth was hot to the touch. The stench of sweaty men and sweaty horses, of leather and chain-armor, was thick in the air. Hot bitter dust filled the nostrils of the men.

Philip read his demands. Of a sudden there was a peal of thunder from the inscrutable sky. The horses reared, and the monarchs, hearing the voice of God, fell apart. They spurred their horses together again to continue the parley, and again there was thunder, more terrible and more awful than before. And there were no clouds in the sky, and there was no rain in the air, and there was no wind from the north, only the two monarchs in the center of the field, and the proud scornful army on the one side, and the small handful of men on the other; and one of the kings was sick unto death; and an impotent God spoke from a sky of brass! Henry reeled on his horse, and his friends rushed forward to prevent him from falling. He made his submission. As he turned to ride away he passed close by Richard his son, and he whispered in a hoarse voice, “May God not let me die until I have worthily avenged myself [204] on thee!” Richard thought it was a merry jest and told it to his companions at the French court.

Henry rode back to Chinon. Never a town in the world can be lovelier than the town of Chinon. In the center is a small square, crowded to overflowing with plane-trees so that in the hottest afternoon the place is cool and dusky and silent save for the eternal rustling of the leaves. An occasional wedding party crosses the square to the church at the west of the town, and the dress of the bride is white against the black evening-suit of the groom. A cart rattles up the cobbled stones. A bell tolls, and a funeral crosses to the church at the east. “C’est la mort,” sighs the garçon in the hotel. But now that the wedding party has reached the church at the far end of the village, the bells ring out: “C’est la vie! C’est la vie.” Henry loved the people of Le Mans, but he loved better the château at Chinon which he had enlarged and rebuilt according to his own plans.

A deputation of monks from Canterbury with a new list of demands was awaiting Henry’s arrival at Chinon. They forced their way through swords to the king’s bed. They trusted that “in thy afflictions thou mayest pity the afflictions of the church.” They forced their way into his presence. “The convent of Canterbury salutes you as their lord. . . .” Henry interrupted: “Their lord have I been and am still and will be yet, small thanks to you, ye evil traitors. Now go ye out. I will speak with my faithful servants.”

As the monks filed out, one of them stopped and laid his curse on the king, who trembled and grew pale at the terrible words, “The omnipotent God, of his ineffable [205] mercy, and for the merits of the blessed martyr Thomas, if his life and passion have been well pleasing to Him, will shortly do us justice on thy body.” Geoffrey the Bastard sat at the king’s head and drove away the flies that were collecting on his sunken face.

The messenger returned from Philip with a list of those who had conspired against the king, to whom the king had promised forgiveness. The king commanded that the list be read. It was handed to Geoffrey. Geoffrey cried, ##8220;Sire, may Jesus Christ help me! The first name which is written here is the name of Count John your son!”

The king sat up in his bed. “Is it true,” he said, “that John, my very heart, whom I have loved beyond all my sons, and for whose gain I have brought upon me all this misery, has forsaken me?” Then he turned his face to the wall. “Now hast thou said enough. Let the rest go as it will. I care no more for myself nor for the world.” He grew delirious. In his delirium, his invincible spirit broke out in passionate denunciations. He cursed the day he was born. He cursed his sons and the God that made them and the wife that bore them; he cursed the blessed sunshine and the birds and all the creatures that lived or breathed or swam. “Shame,” he muttered. “Shame on a conquered king!”

He died.

On his feet were put golden shoes with golden spurs, on his finger a ring of gold, and in his hand a golden scepter, and on his head a golden crown. He was carried to Fontevrault by the little road that follows the river Vienne as far as La Rocherau woods — it is a few yards to the east of [206] the present highway — where it turns west and becomes a country path shaded by huge trees and leads to an ancient château, now used as a farm-house. The farmer is very friendly and will give you a glass of his own wine, which, if you take the trail in June, you will find welcome. It is

Cool’d a long age in the deep delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

It is full of the warm south, and beaded bubbles rise to the brim. From the farm of the château, the trail turns north and winds back and forth and in and out and around, skirting this wall and that field until it reaches Fontevrault itself. When they carried Henry along this trail there were monks chanting and knights in armor; the peasants in the fields no doubt stopped their work to bow their heads as the procession passed, and irreverent boys ran along ahead and followed behind.

Richard hurried to Fontevrault from Tours, where he had been celebrating his victories. When the king’s body was carried into the chapel, it was found shorn of its golden ornaments; and when Richard demanded them back, the treasurer as a special favor sent a ring of little value and an old scepter. As a crown, Henry wore the gold fringe torn from a prostitute’s petticoat, and as a robe, the petticoat itself.

Richard prayed before the altar, and as he prayed blood spurted from the mouth and nose of his dead father. It was wiped away, and again he prayed, and again the miracle was wrought. Richard shuddered and ran from the abbey.