Périgueux

Click on the footnote number or mark (*, §, †, etc.) and you will jump to it, then click that footnote number or mark again, and you will jump back to where you were in the text [That line will be at the top of the screen].

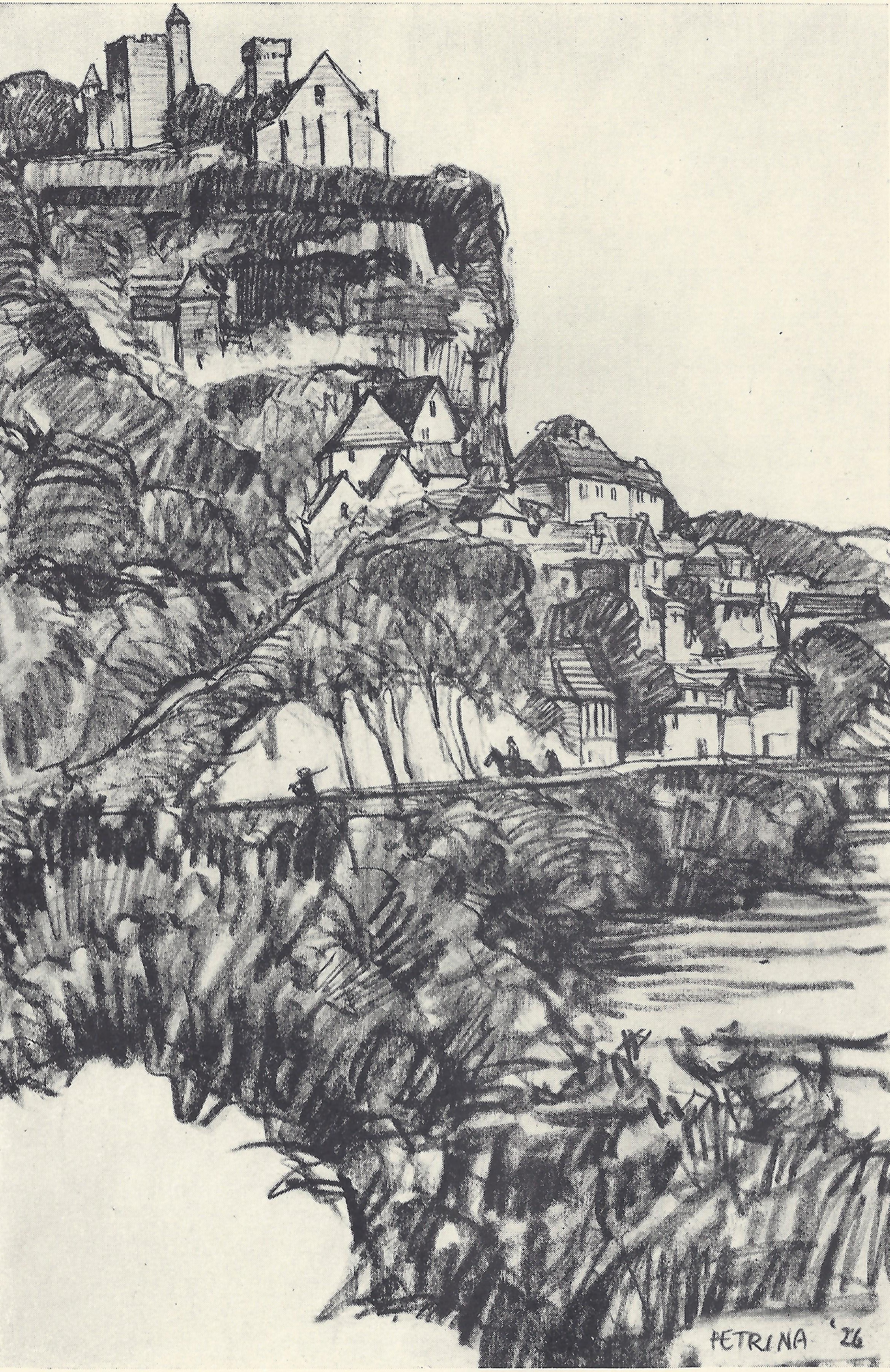

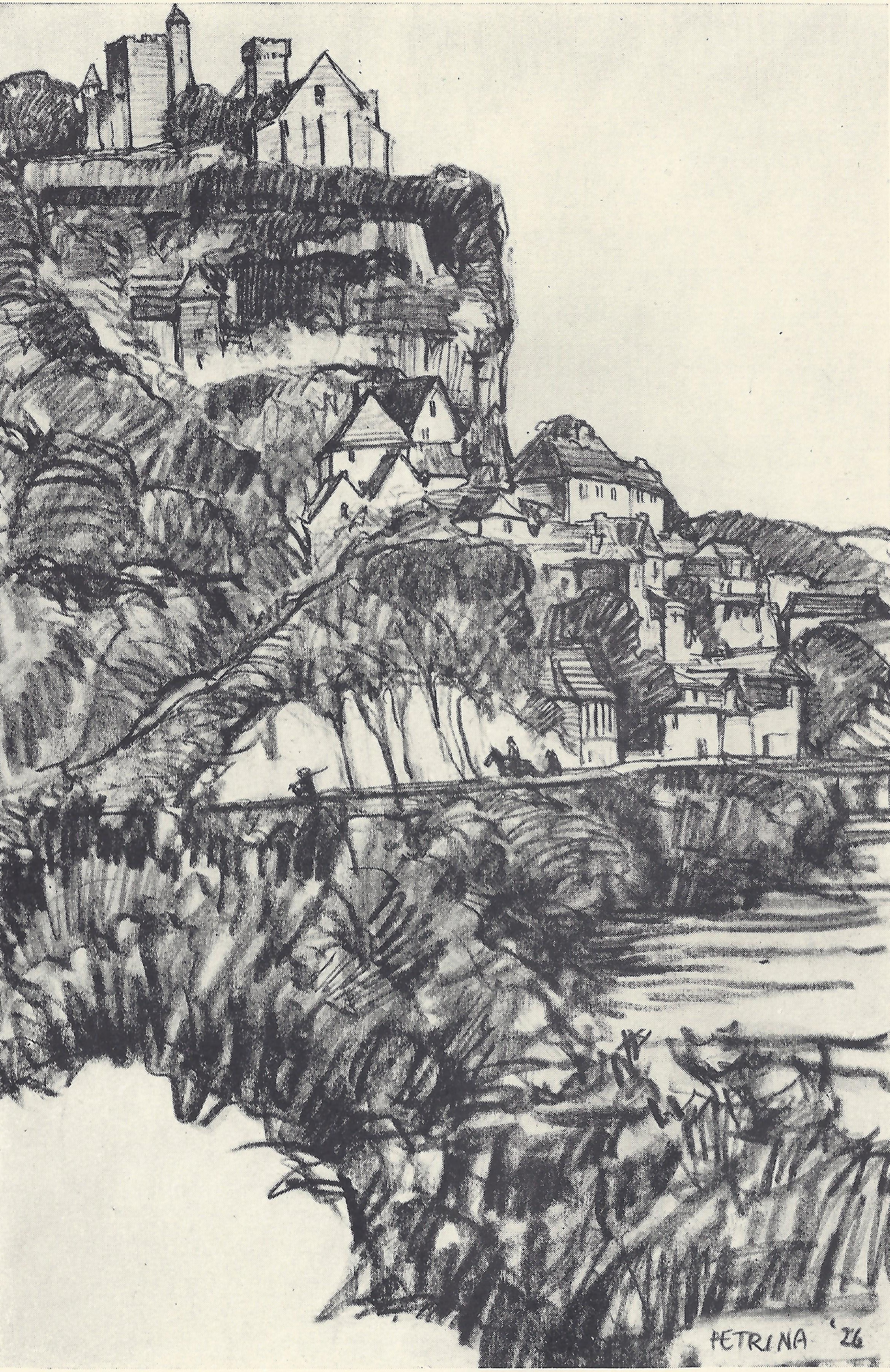

From Trails of the Troubadours, by Ramon de Loi [pseud. Raymond de Loy Jameson], Illustrated by Giovanni Petrina, New York: The Century Co., 1926; pp. 129-158.

TRAILS OF THE TROUBADOURS

by Raimon de Loi

Périgueux

WHEN the afternoon sun strikes the west façade of the cathedral at Le Mans, it sends through the window a brilliant ray which collects like liquid light directly in front of the altar. The dust-motes rise in it and flow upward and outward through the window. A minor and very senile cleric loiters about the tomb of St. Julian; an old woman reminds you that life is bitter; she hints that the chastely erotic aspirations of her youth were illusory and urges you to buy a candle in honor of the patron saint both of Le Mans and her humble self — St. Julian, particularly beloved by Henry II of England. Unfortunately I cannot assure you that the ray of light fell in exactly the same way on that Christmas afternoon when Henry and his whelps quarreled after parading in pomp through the crowded church; nor can I assure you that an old woman bedeviled some casual Anglo-Saxon visitor who fled from the turmoil of the great hall for a moment of peace. These things are dark, and no man may say for certain whether they did or did not happen. Whatever the facts may be — because the sun strikes the church to-day in much the same way it struck in 1183, and because old women are pure because [132] life is hard, I believe the facts are much as I have suggested — this is certain, that when Richard the Lion-Heart, hating his father and brother, broke through a circle of men-at-arms and fled from this same church southward to Poitiers as you have heard, he left in the great hall three and perhaps four of the dancers who participated in the tumultuous and in many respects tragic political saraband of the twelfth century. He left his fat father, King Henry II of England, the man who had never been defeated, fretting and fuming at the impudence of the young pup. He left his brother, handsome young Henry, who recently and arrogantly had been crowned king of England in order that Richard by treason and trickery might not get possession of the crown — as by treason and trickery he ultimately did get it; he left, finally, cynical Bertrand, viscount de Born, master of the castle at Hautefort, a young man well brought up who was at the same time aristocrat and journalist, patriot and traitor, sycophant and troublemaker, man of affairs and time-server.

These three may have taken counsel in one of the recesses of the hall, that is to say in one of the embrasures formed by cutting the windows in the walls of the building. These walls were so thick that when a window was cut it was necessary to make a small alcove in the room, an alcove large enough to be made into a retiring-room which could be shut off from the rest of the hall. These windows, the larger ones of the room, always faced the court of the château and looked out upon the manifold activities of the community, the loitering servants idling about their work, a groom exercising a horse or a page polishing the [133] armor or sharpening the sword of his master, an infinite number of dogs fighting and snarling over bits of refuse or snapping at the meat being carried from storehouse to kitchen. Through the windows and into the room came the noise of activity and the hum of talk, the indescribable sound of the busy business of keeping one’s self human and amused, the sound of that curious activity characteristic of all times and places, the activity of being modern and up-to-date.

Each of these three, the old king, the young king, and the Viscount Bertrand, were moderns. The old king was a modern, and for those who care more for events than for character, he may have been the most modern of the three. One may say what one likes about the theory of sexual morality which led or rather followed this man into various temptations to each of which he seems to have succumbed — not in turn, but simultaneously, he is said to have violated several of his daughters-in-law and to have planned to marry one of them himself — one may point out that his religious convictions were peculiar and that his conversation was not suitable to the modern drawing-room either in tone or intention; and yet the fact remains that this mountain of flesh and iniquity did understand the theory of the modern state better than any of his contemporaries, and that out of the anarchy which was England when he landed there emerged the English nation. Philip the comely of France beat old Henry in the end, and beat him by carrying old Henry’s methods a step further; but Philip, the son of Henry’s old rival in love and war, represented the new generation that had learned a [134] thing or two from the old. The old king refused to take sides in this quarrel with his sons. Young Henry, his favorite, had given him trouble enough; let the youngster see what he could do. If the young man were chastened in the struggle which was to ensue, it would be a valuable lesson to him; and if Richard were overcome, so much the worse for Richard. After all, the quarrel was within the family. The old king jigged northward through Domfront and Caen to London, there to watch the progress of events.

Young Henry too was a modern; but he represented the social aspect of the modernity of the time. Young Henry was the fine blossom of chivalry, the hero of the tournament, the last word in social elegance. To-day institutions have changed; the tournament has been supplanted by the more refined sports of polo and golf, and chivalry has no more to do with the horse which gave the rank its original dignity than the rough horse-play which concludes a bootleg party. The human spirit seeking its own comfort and aggrandizement has forgotten those things about the age of chivalry which might be unpleasant and has remembered only those other things which envelop it with the oil of unction. The medieval tournaments of which young Henry was the hero were of a brutality as much worse than the brutality of a Spanish bull-fight as the lives of two men are more significant than the life of a bull. Although it was no doubt pleasant to sit of a spring day on the bleachers and watch the royal pavilion thronged with lovely ladies and hear the sonorous herald and watch the knights ride down the field six abreast with [135] lances poised, it may have been less pleasant to see a man run through the body by a spear, to see the spear — by a thrust which was, no doubt, strong and true — run through a man’s throat and break off, and to know that the blare of the trumpets were to cover his choking cries as he writhed on the ground like a fantastic thing. Young Henry was the hero of tournaments. If you killed your man, you got his horse and armor, which were valuable. If you were killed you lost your horse and armor, for which in the nature of things you could have few regrets. Tournaments were good business.

Bertrand de Born allied himself with young Henry and took charge of the publicity of the war. He undertook to urge upon his friends the injustices which they had suffered under Richard, although all concerned knew that Richard’s misrule had been no worse than Henry’s would have been. He kept Henry’s ardor at white heat by pointing out that although he was king in title he possessed no lands, castle, or revenue; whereas his brother, Richard, a mere duke, was in effect the king of a large territory. He persuaded the young king that all the Aquitanian barons would rise against Richard if Henry led them into battle. He himself, Bertrand de Born, the young head of an old and important family and a poet of some note, promised by his poetry to inflame the hatred which he said the Aquitanian barons felt for Richard. He placed himself and his service at Henry’s command.

He affected great anger with Richard, whom he called a profligate, and with the old king, whom he called much worse. There is in his poetry some faint gleam of that [136] passion which in more recent years has been called patriotism; but one must not be deceived. The more or less altruistic love of country which is one of the highest civic virtues to-day was unknown at a time when the conception of country had not yet been formed. One’s country was one’s own estate. The thousand or so castles and counties that constituted the duchy of Aquitaine were not united in any common interest except the interest that each felt in its own aggrandizement. They were no more than a thousand or so castles and counties that were forced by expediency to pay more or less willing homage to a central duke. The more frequently the person of the duke changed, the more frequently would the knights and chatelaines by the devious methods of back-stair politics be able to enlarge their various rights and powers. “When the big ones fight,” said Bertrand de Born, “the small ones grow rich.”

Young Henry decided upon war; and Bertrand, pretending great fury against Richard and the old king, spent the next three months traveling, chanting his war-songs at every château, and inflaming the knights and chatelaines to revolt.

Although there is much doubt as to the exact trail that he followed, the evidence is clear that he stopped at Angoulême, Périgueux, his own castle of Hautefort, and then proceeded south via Rocamadour to Cahors and thence east to Toulouse. The trail from Hautefort to Toulouse formed one leg of the triangle. From Toulouse he turned westward to Bordeaux along the old Roman road. Thence he probably turned northeast again to Périgueux. [137] The last leg of the triangle is so vague that I am inclined to think he sent out ambassadors and musicians to sing in his place and that he returned north by some shorter route. There is little doubt that Bertrand himself went as far as Toulouse between Christmas and the early spring, when the actual fighting began. If an ambassador was sent to Bordeaux, it may well have been Henry’s brother Geoffrey, who at that time was in love with the poet Jaufre Rudel, whose posthumous passion for an unseen mistress has stimulated the philosophic imagination of Robert Browning, Rostand, and others. But of Rudel there will be something to say later.

Shortly after Richard broke away from the crush of dancers gathered at the château of Le Mans to pirouette southward, the old king with his ingrowing toe-nails jigged off to England, and Bertrand de Born a day or two later set off on Richard’s trail for the south. There is no reason why he should not have called on Richard at Poitiers; they had been friends from boyhood, and Bertrand had here an opportunity to harden Richard’s heart against Henry and make certain that a war would be fought, an opportunity which a man like Bernard delighted to make use of. At Poitiers too he would have the opportunity of paying his respects to the troubadours who thronged the court of Richard, and of spending, in order to cement their friendship, some of the money which Henry probably gave him. Two of these poets, Gaucelm Faidit [138] and Folquet de Marseille, were certainly with Richard at this time. A third, Marcabrun, may have been a member of the party.

Gaucelm Faidit was a fashionable poet and profligate. His father was a bourgeois and was connected, during Gaucelm’s boyhood, with the legation at Avignon, which during this century was the seat of the papacy. He sang, according to his biographer, “the best of any man in the world, he composed very well both the words and the music of the songs, and his contemporaries said that he could match good words with good sounds.” Another biographer adds that Gaucelm was a “man of good cheer, living carelessly, for which reason he lost his entire fortune by playing at dice.” He became a “comedian,” which means, probably, an actor manager, and sold the tragedies and comedies which he made at two or three thousand pounds and sometimes at more, “according to their invention.” He himself arranged the scene and composed both words and music. Thus he could take for himself the entire revenue. “He was so liberal, prodigious and gourmand in his eating and drinking that he spent all the profits of his poetry and became immeasurably fat.” He married a lady called Guillhaumone de Soliers, whom by his sweet words he had seduced from a monastery at Aix en Provence. “For twenty years she followed him through the courts of the princes, and she was very beautiful, well trained in all the virtues, and sang very well all the songs which her Gaucelm made for her. . . . But because of the dissolute life they led together she became as fat as he and, surprised by a malady, she died.”

[139]Together they wandered over the narrow and friendly medieval trails, fat Gaucelm with his Gargantuan laughter and his weakness for the ivories, for pretty words, and for pretty Guillhaumone, who was connected perhaps intimately with the proud Soliers of the Château de Soliers in the south. On warm summer afternoons they would lie under the trees laughing in the sunshine. On cold or rainy days when Guillhaumone grew tired he would put his arm around her and help her over the muddy roads. When, in the days of their poverty, they came to a tavern, they would enter with a flourish: “I am Gaucelm Faidit the singer of songs, and this is Guillhaumone de Soliers who sings divinely.” They would do their little act and hope for a bed and a meal. When Gaucelm lost his money his reputation as a poet decreased, and when Guillhaumone left the convent her friends snubbed her. “For a long time they were unfortunate and miserably poor, receiving no gifts or honours from any knight until” — after Guillhaumone’s death — “Duke Richard with whom he lived until 1189 took pity on him.”

Another biographer presents a slightly different account. Here Gaucelm is said to have been the son of a bourgeois in Uzerche in the bishopric of Limoges “who sang the worse of any man in the world.” He is said to have received thirty, fifty, or sixty livres — sums more worthy of credence than the fortunes mentioned by the other writer — for his comedies and tragedies. Both agree that Gaucelm was immeasurably fat. The second biographer declares that Gaucelm married une soldade, a certain Guillaume d’Alest, whom he seduced from a monastery [140] of nuns. After the death of Duke Richard, Gaucelm stayed with the marquis of Montferrat, who was so charmed by the comedy, “L’Heregia dals Preyres,” that he gave Gaucelm “rich and precious gifts of clothing and of harness and put a good price on his inventions.” The best though not the most characteristic of his poems that I have seen shows a regrettable cynicism. It begins:

Many a man is much more generous

In gifts of evil than gifts of good. . . .

If Gaucelm Faidit represented the Bohemianism of Richard’s court, Folquet de Marseille, like Bertrand de Born, represented its eminent respectability. Folquet was the son of a very wealthy merchant of Marseilles. After his father’s death he devoted his time and his fortune to the services of “valiant men and arrived with them to great honour.” He was extremely wealthy and composed very well and sweetly in the Provençal tongue, although he is said to have sung better than he wrote. He was pleasant and liberal in his manner and beautiful in his person, which latter fact may account for his friendship with Richard, who shared his mother’s passion for handsome young men. At one time he, like Peire Vidal, was enamoured of the fair Adalasia, the powerful countess of Les Baux. As she was blessed with an impenetrable chastity Folquet devoted his talents to the extirpation of heretics (he was the leader in the prosecution of a group of men who believed that man was not created in an instant in the Garden of Eden but was the result of a slower development) [141] and died, if not in the odor of sanctity, at least enveloped by the odor of respectability, an archbishop of Toulouse.

Poitiers is no longer the rendezvous for poets, either fat or respectable, but there must have been a great party there one spring when that exquisite and fashionable young gentleman, the viscount de Born, rode over the drawbridge and, with his secretary and singer, a beautiful lad from Périgueux whom he was training in the art of poetry, was shown into the high-raftered hall and welcomed by Duke Richard. Marcabrun the cynic was probably in the hall with the others, although whether he was on the side of Richard or of Bertrand is uncertain. This, however, is recorded, that when Richard, Bertrand, and Marcabrun met on this occasion or another, Richard swore by all the saints that Marcabrun was a better poet than Bertrand, and Bertrand swore that he was not. Richard had the two poets locked in their rooms and gave them forty-eight hours to show their art. At the critical moment, Bertrand’s inspiration failed him. He spent two days playing chess with his singer and listening to his rival, in an adjoining room, committing his new poem to memory. Bertrand, too, learned the poem and, requesting that in the tournament of song he be permitted to sing first, anticipated his rival. Marcabrun was furious until Bertrand pacified him by the explanation that in his zeal to please Richard he had become so dissatisfied with everything that he had done that he had decided to join his friend Marcabrun, whom he admitted to be his master in the art of poetry in doing homage to the puissant duke.

From Poitiers Bernard de Born proceeded southward toward Angoulême and the country of the honest Angoumois. The trail he probably followed is now covered by a secondary road, and accompanied — now on one side and now on the other — by the railway which leaves it at St.-Maurice-la-Clouère on the north side of a river and Gençay on the south. St.-Maurice was the sometime home of a formidable saint, now all but forgotten, and Gençay was the seat of a powerful castle now in ruins. “Maurice,” says the Golden Legend, “is of amarus, that is bitter, and cis, that to say vomiting odour, or hard, or of us, that is to say counsellor or hasty. He had bitterness for his evil idolatry and dilation of his country; he was vomiting by covetise of things superfluous; hard and firm to suffer torments; counsellor by the admonishment of his knights and fellows; hasty by ardour and multiplying of good works; black by despising himself.” He was one of the 6666 knights who were slain defending Christianity against Maximian; and the remains of these saints, like those of the thousand virgins of Cologne, were scattered all over western Europe and did great miracles. If placed on the sea during a storm, they will still the waves; they can revive the dead. The relics of Maurice demand a proper observation of the Sabbath. Once when a “paynim workman” insisted on repairing the church where part of Maurice was buried and insisted on doing this on Sunday, the only day of the week when he would do any work at all, and worked during the hour while mass was being [143] celebrated, the saints appeared to him all shining in light and beat him and admonished him so that thereafter he gave up his evil practices and did not work even on Sundays and was christened and became a good Christian.

At Gençay the road branches and runs southwest through Civray and Ruffec, the native home of the mystic truffe to St.-Amand-de-Boixe, where, five hundred years earlier, Theodobert, the son of Chilperic, perished, and on to Angoulême on the hill.

Angoulême was the home of Gerard, the bishop, who became involved in a quarrel with William of Aquitaine and the papal authorities and was chastened in a remarkable manner by St. Bernard. The château of Angoulême, except a tower and a stairway, has been destroyed to make room for a modern court-house; the cathedral, although it still retains much of the grandeur of the Romanesque style, has been rebuilt at least twice. However, when Bertrand de Born, coming in on the road from Ruffec, climbed the hill to enter the city by the northern gate and by what is now the Rue de Paris just above the grotto in the cliffs, where the holy St. Cyprian is said to have achieved holiness, when he had paid his respects first to the chatelaine and then to God as was the custom in those days, he must have felt, if he felt about those things at all, that the cathedral which was in his time relatively new and the château which was old and formidable were both, in all respects, adequate.

As one proceeds south from Caen and the Abbaye-aux-Hommes, for example, to the Mediterranean, the architecture loses that nervous irritability of spirit which is [144] characteristic of much of the Gothic with its aspiration after things unknown and its suggestion of architectural catharsis, to assume broader, more placid, more realistic expressions. The old wooden church at Angoulême, built on the site of an older pagan temple, had been destroyed in the early part of the century; the new stone structure had been completed only a few years before Bertrand’s arrival. Here as elsewhere there was a sense of newness about the world: a new poetry was being made; new philosophies were being preached; new churches were being built in new ways; and every day or two there were new political bosses. This sense of change which in our own epoch we dignify by the name of progress, this newness and freshness that clothed the body of the earth and the thoughts of men, has led sentimental historians to believe that the people of the twelfth century were naïve and simple. As a matter of fact, they were simply, even as you and I, modern and up-to-date.

Although Bertrand evidently persuaded the lords of Angoulême1 to participate in the struggle against Richard, their participation was not whole-hearted. To their defection — and Bertrand gives a long list of traitors — is attributed the failure of the campaign.

When Bertrand left Angoulême, he traveled east by [145] north toward Limoges via a short cut which took him past the Château de Rochefoucauld, where he enlisted the co-operation in the plot of an early ancestor of the moralist Rochefoucauld. The warrior lord has been forgotten, although the château which he built and the descendant whom he begot are still ours. He may have been a distant relative of Bertrand’s. From Rochefoucauld, Bertrand proceeded to Rochechouart and thence northeast to St.-Junien, where there are churches and a bridge of the twelfth century and paper-mills and a glove-factories of the twentieth.

FOOTNOTE

1 Angoulême is not the capital of Anjou as is reported by Henry James in his “A Little Tour of France,” p. 124, but is the capital of the ancient duchy of Angoumois. The political geography of France in the twelfth century in broad outline was as follows: proceeding from north to south, the duchies were Normandy; Maine (chief city, Le Mans); Anjou (chief city, Angers); Poitou, which takes us as close to Mr. Cabell’s Poictesme as any human foot may come (chief city Poitiers); Périgord (chief city, Périgueux).

Bertrand’s next stop, and it was relatively long, was Limoges. For an entire day, from St.-Junien, he had been traversing broad and rich forests and green fields in the rain which raineth every day, the eternal rain of the Limousin. Here and there rising abruptly from the flat plains are rounded granite hills with, maybe, a church on top or a small village with the walls of another civilization still intact, and at times the fields give way to the purple of the heather. The north, the center, and the south of France are each distinguished by a particular landscape and a particular historic rhythm. In the north one is active and practical. One builds protections against the winter cold, one creates, one plays complicated games for the sheer fun of being alive. The landscape in the summer is rich and green. In the south one is indolent. One realizes that nothing, after all, is worth doing; that it is well to sit in a café and sip syrups and to read the “Action Française” and to grow fat and slightly blasphemous in a world which, [146] if not the best possible world, it is, at any rate, tolerable, if one takes it as it comes, good and bad together. Limoges is neither of the north nor of the south but of both. The inhabitants are, in their way, as decent as most, but they are not quite certain whether it is worth while being decent. They would like to get out and hustle and do things; but after they have made a fair start, it occurs to them that nothing after all is quite worth while doing, or one group decides that it wants to do one thing and another that it wants to do another thing. Then there are great arguments and a broken head or two, and both sides remain just where they were or go to the tavern to repair their heads and their differences.

When Bertrand came to Limoges there were two towns. One of them was “the city”; it was fully fortified, closely and compactly walled, and had been built many hundreds of years earlier around the church, now the cathedral of St.-Etienne. The other was “the town.” It had grown up out of the agglomeration of houses, monasteries, and chapels which collected about the tomb of that vital saint called Martin who spent his life in restoring people who should have remained dead and in carrying on edifying if somewhat platitudinous conversations with the devils who caused the ladies of his town much concern.

The tradition of St. Martin is as confused as the other traditions that cluster about Limoges. The saint is said to have been one of the crowd that heard Christ preach. He was a friend of St. Peter and was sent to Limoges to Christianize the heathen. The governor of Limoges was a cousin of that Nero whose fondness for feminine finery and [147] violin playing has become proverbial. He is credited with having burned more martyrs, that is to say with having made more saints, that is to say with having, by his influence, converted more pagans, than any other man in history. He has doubtless been given some suitable reward in heaven, although I am told that Nero actually burned fewer Christians than he is credited with and that the claims of his enthusiastic biographers are somewhat exaggerated.

On his way from Rome to Limoges, St. Martin stopped at Tulle, where he learned that the lord’s daughter was being persecuted by “an ugly heathen devil.” The devil on seeing the saint approach knew that his time was up and begged humbly and politely not to be sent to the “ugly abysm of hell”; and the saint, being at heart a kindly though a just man, sent him to a “place desert where bird, ne fowl, ne person dwelleth.” He uttered this command in so terrible a voice that the maiden was literally scared to death. She fell over lifeless. Death, however, was nothing to this saint. He took the maiden by the hand and in a kindly voice told her to arise. She arose and was converted and became a good Christian.

When he arrived at Limoges, where he found many devils to exorcise, he was taken up by one Susanna, and he healed one that “was frenetic.” He went to the temple, probably the temple of Jupiter which stood on the site of the present cathedral, and, like a good Christian and member of a superior civilization, began breaking the idols of ivory and marble and gold and silver. The priests seem to have been somewhat irritated by his summary method of procedure. They set upon St. Martin one and all and bound him and put [148] him into prison. But the saint was potent. With the help of God he killed many of the heathen, and frightened the others so badly that they came to him in his cell and began to bargain with him for his freedom. They said, “if you bring back our friends to life, we will set you free and permit you to baptize us.” St. Martin agreed and in one day baptized twelve thousand creatures, men and women together.

At her death, Susanna commended to the saint’s care her daughter Valérienne, who learned in some mysterious way that a man called Stephen was coming to Limoges. Now whether she knew that men called Stephen were dangerous or whether she had heard that this particular Stephen had designs upon her is not clear; but as soon as she heard of his coming, she took protective measures. They were useless. As soon as Stephen saw her he wanted her. She explained that she was busy doing other things, but in vain. Stephen gave orders, and all things stopped together. His squire, who cut off Valérienne’s head, heard angels singing as her virginal soul was borne into heaven; he came back to his master and told about it and fell down dead. Stephen was so frightened by these events that he clad himself in hair garments and begged the saint to restore the squire to life, and the saint did, and Stephen and all his followers were baptized. Valérienne, the pure maiden, was permitted to remain dead. The wicked squire was restored to life.

Even the devils played fair with this saint. Once he was dedicating a church in Limoges, perhaps the church now called St.-Michael-des-Lions, and had commanded all the [149] people there assembled to be in a state of perfect chastity. A knight and a lady evidently possessed of devils were brought before him. St. Martin said to the devils, “Why did you take possession of these people?” The devils answered, “You commanded that all your congregation should be in perfect chastity; but these have been doing evil things and we thought that since they had not obeyed you, we might do as we pleased.” Then St. Martin, seeing that they were civil devils, asked the lord of the country what should be done. The lord said that the devils should be driven out, and that the knight and lady had had a good lesson and would obey the saint next time. The saint drove the devils to a desert place, where, no doubt, they still remain, gibbering through the moor, unhappy, desolate. He was a potent, pleasant, kindly man, was St. Martin, and is said to have been the child on whose head Christ laid His hand when He said, “Except ye be converted and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.”

Limoges and the surrounding country of Limousin are the place where many poets have chosen to be born. Bertrand de Rascas, a “sedate and well poised” poet, won great fame at Avignon after giving himself to the writing of poetry during his youth. “He despised the state of marriage, and all the great and learned men who visited Avignon to see the splendours of the papal court would call on Rascas to see him and hear him speak.” Giraut de Bondelh was also of Limoges. “He was born of poor parents, was well behaved, had good sense and became the best poet in the Provençal tongue. He was called the [150] master of the troubadours and was well liked by all valiant men and wise, and by lovely and learned ladies who knew how to enjoy and make poems in the Provençal tongue. All winter he spent studying poetry and literature, and in the spring he took with him two excellent musicians and made the tour of the courts. He always refused to put himself in the service of the rich princes, but they offered him much money and gave him rich presents. He said that he disdained both the loves of the most beautiful ladies of his time and the yoke of matrimony. He was most sober in words and continent in person, surmounting in these virtues all the poets who have lived before or since. . . .”

At Limoges, Bertrand de Born was in his own country and speaking his own dialect. Here he became more than the ambassador he had pretended to be while surrounded by men who might be friendly to Richard. Here he knew his people, and here he began the series of war-songs, the exhortations, and the arguments that kept the great ones in the saddle, fighting each other, in some cases, to the death. The appeal made by the advertising man of the twelfth century is strikingly similar to the appeal of his modern descendants. He regretted the brutality of war but insisted on its necessity. He appealed to self-interest. He called upon his countrymen to right their own wrongs and to rescue from misery the unfortunate Eleanor. Self-interest, vanity, and sentiment were aroused for the cause of Henry. “Do not believe,” he cried in one of his poems, “that my humor is bellicose merely because I like to see the great ones charge each other lance in hand. It is only when the great [151] ones fight that the lords and vassals” — and perhaps too the poet ambassadors — “are prosperous, for I swear to you that the great ones are larger of heart, more generous of hand and more complacent in words when they are at war than when they are at peace.” “The danger is great,” he said in another place, “but the profit is greater.”

He sang a song for Eleanor, a song which is the more irritating because it adds little to our knowledge of Eleanor’s position. All that is known of Eleanor at this period is that the old king had put her away somewhere for safekeeping but that he had been unable to keep her quite safe enough to prevent her from intriguing with her sons and supporters. Yet if her sons had wished to see her free they might easily have done so; but Henry was not his mother’s favorite and had little to hope for from her, and Richard may have been busy with other things, or, more probably, had a fairly clear conception of the extent of his mother’s power and was glad enough to keep her out of his way

Bertrand’s musicians sang:

Rejoice, thou land of Aquitania. Rejoice, ye Poitevin barons. The scepter of the eagle king [Henry] will be removed. Maledictions and curses upon him who has dared to raise his sword against his master the king of the south.

Tell me, double eagle [Eleanor], tell me where you were when the eaglets fluttering from the paternal nest dared to bury their beaks in the bosom of the eagle king. Why have you been raped from your county and borne away into a strange land? Songs have been changed to tears. The sound of the cithern has been replaced by the funeral chant. Nourished during your warm [152] youth in royal liberty, you sang with your companions or danced to the sound of the soft guitar; but now you mourn, you weep, you consume yourself with sorrow. Return if you can, return to your cities, poor prisoner. . . .

From Limoges, Bertrand de Born went south to Périgueux. He left by the southwest gate along the road which is now called Avenue Baudin and followed the Vienne River westward for a league and a half, where he turned south into Nexon through a gate which still looks much as it must have looked when he saw it except that now it has machicolations and when he entered it was simply a plain gate in a plain wall. Here he turned west to Châlus, a poor place, held a few years later by one Vidomar, a sturdy man who knew well how to stand up for his rights. There is still something sinister about Châlus. Two ruined keeps dominate the village, and the village itself fawns about their feet. When I walked into the tavern there a year ago — thirty-five-odd kilometers is a longish walk on a warm spring afternoon — I heard the garçon cry: “Mon Dieu! Un Anglais!” (One must not forget that tourists who look English are, to these people, Englishmen. Philosophy and the arts died in this region a few years after Columbus discovered America.) The garçon led me to a bedroom with an odor. The odor was hearty and friendly. It prognosticated hundreds of merry little bedfellows. I declined with thanks and bought a bottle of wine, a slab of cheese, and a yard or so of French bread. I washed my face and hands in the little stream a few yards above the municipal laundry, where a good wife on hands and [153] knees was transforming her husband’s Sunday shirt — who knows how in the muddy water — to a pristine whiteness and proceeded up the hill to the keep. Here I carried on a one-sided conversation with the present lord of the castle, a sleepy lizard.

What hospitality Bertrand met in Châlus I do not know; but some thirty years later, after Bertrand’s little dance had been danced and the young king and the old king were both dead, Richard the Lion-Heart came before Châlus, Richard the Lion-Heart and his faithful queen Berengaria, Berengaria of the yellow hair. It was the last trip they took together.

Richard must have been an amiable fellow. His poets, Gaucelm Faidit and Blondel, whom he paid well for their work, have said many pleasant things about him; and the poets who honored him with their friendship, Folquet and the exquisites who were setting the fashion in singing, fighting, and love-making, found him a good fellow and capable of anything. He had a witty tongue, and although he could fly into insane rages, he was willing to forgive any fault if it could be made the subject of an epigram. When, upon his return from the Crusades, he had driven the minions of his usurping brother John from the kingdom and John was brought to him for forgiveness, Richard said, “I forgive you, John, and I wish I could as easily forget your offense as you will forget my pardon.” At another time a revivalist friar urged Richard to give in marriage his three evil daughters. “Thou liest,” said Richard, “for I have no daughters.” “In sooth,” replied the preacher, “thou hast three evil daughters, Pride and Avarice and Luxury.” [154] “Then,” said Richard quickly, “I will give my pride to the Knights Templar, my avarice to the Cistercian monks, and my luxury to the bishops.”

It was avarice that brought Richard to Châlus. Word had been sent to him in Poitiers that a peasant of the estate of Vidomar had, while plowing, discovered a Roman treasure hoard. Richard sent word demanding half the treasure, his due, as overlord of the country. Vidomar answered that the treasure was merely a handful Roman coins, to which Richard was welcome. Richard, who in the nature of things could know nothing at all about it, insisted that the treasure consisted of golden statues of an emperor and his family seated at a golden table. Accompanied by his queen Berengaria and a small body of troops, Richard paid a visit to Châlus and, if he had been lucky, would have taken the castle in place of the treasure. While he was inspecting the fortifications one of Vidomar’s men, whose name was Gourdon, let fly an arrow from the ramparts and was fortunate enough to pierce Richard’s shoulder. A wound in the shoulder in those days was of no particular importance, and it was not until the castle had been taken that the awkwardness of Richard’s doctors came to notice. The wound began to mortify. Berengaria of the yellow hair is said to have tried to suck the poison out with her lips; ladies in those days were capable of acts of devotion, and Berengaria’s faithfulness was proverbial. Richard had deserted her once for the wild women of Poitiers, the gay companions of his youth, and after she forgave him, she took good care that he should never again be out of her sight.

[155]The day the castle fell all the garrison except Gourdon, who had fired the fatal arrow were hanged on the walls. When Gourdon was brought before Richard and questioned, he boasted of his deed. “It is thou,” he said, “who didst slay my father and my brothers. Now slay me. I do not fear thy tortures.” Richard forgave the man and gave him a sum of money, a chivalrous action which the sentimentalists remember. He sent him with a letter to his lovely sister, Joanna of Toulouse, whose charm and beauty have been sung by many a poet. She, with characteristic Angevin tact, had the skin neatly removed from his body by an art which is known as “flaying alive,” from which operation Gourdon died. The operation must have required some skill and a steady hand. It could be performed in two ways. Sometimes the practitioner began at the shoulders. The skin was removed in inch strips to the waist. Then the prisoner was set free and lashed with whips. As he ran he would trip and fall on his own skin, which hung down and impeded his flight. Other practitioners began at the feet and the skin was left comparatively intact. When the victim became noisy, the apron of skin was thrown up over his head.

Let you not forget that this is the age of chivalry, the age when one was as courteous to one’s enemies as to one’s friends, when brave knights rescued trembling maidens, when irresponsible knights-errant wandered through the country fighting with anybody who showed resistance, and when steel clanged on steel in a fair fight. The age of chivalry was an age when maidens changed hands with sometimes alarming frequency. When the knights [156] fought, they won for their pains sometimes a castle or perhaps merely an armor or a horse, but the point is that when they won they won something more than the smile of their sovereign or their mistress. The smile of the sovereign was of little value unless the sovereign had something to give away. The age of chivalry, which was also the age of the troubadour, was a hard-bitten and realistic age, and the flower of chivalry was a blue flower dreamed about by a group of rather effeminate poets who sang for the amusement of young ladies who were resting from the more serious business of life.

There were no ghosts on that night when Bertrand de Born stayed at Châlus, but could this viscount who delighted in the misfortunes of his friends and enemies have foreseen the events which were to happen there later his spirit would have gloated.

From Châlus Bertrand went on southward through Thiviers and Savignac-les-Eglises, and what he said I do not know, and what he saw I have forgotten. Finally he reached Périgueux. He was ferried across the river Isle near the present Place de l’Abattoir and followed the street that now bears his name to the château, which had been begun two hundred years before he was born and was not completed until four hundred years after he was dead. The Perigordians are an obstinate race. When the Romans came to the place they built themselves walls and a villa. Later the Romans were driven out and the Gauls entered; and they built themselves a villa at exactly the same spot, and they said, like many a modern Perigordian, “If this place was good enough for the Romans it is good enough [157] for us.” But they could never make the place really suit them. They built and changed and modernized and brought up-to-date and remodeled and rebuilt until the Huguenots in fury — or despair — tore it down a couple of centuries ago — all except two towers.

At Périgueux, Bertrand was kept busy, for the Perigordians are slow to take hold of a new idea. He played upon their sympathies. “Daughter of Aquitania, raise thy voice like a trumpet that thy sons may hear it, for thy day is approaching and thy son shall deliver thee and thou shalt see again thy native land. Thy tears are thy bread both day and night. Where is thy royal court? Thy band of poets? Thy counselors of state? Many of them have been dragged to a foreign land, many have suffered ignominious death, others have been deprived of sight and wander alone in a strange land. . . .” Under the influence of Bertrand and his friends, Périgueux entered the war. When it learned that the forces of Richard were victorious, it withdrew, with characteristic caution, and thus saved itself the humiliation and expense of defeat. Brave Périgueux! It stood two sieges but was never taken.

To-day Périgueux has a dual personality. The old portion, the section of the château and St.-Etienne, is no longer the center of affairs that it must have been in the twelfth century. Then the town around the château was one city; and the town around the monastery, now the cathedral of St.-Front, which, by the way, is very like St. Mark’s in Venice, was another. As the town grew the old city was superseded by the monastic town. The busy Perigordians never tear down. There are the remains of Roman ramparts [158] and a Roman arena and vestiges of the old wall. On one of the arches the moss has grown into a pillow, and one afternoon I shall return there and smoke a pipe or two between showers under a deep blue sky.