[BACK]

[Blueprint] [NEXT]

<><><><><><><><><><><>

From The Pall Mall Magazine, Edited by Lord Frederic Hamilton, Vol. XIII., September-December, 1897; London; pp. 509-516.

509

No. 1.

FOWLING IN BYGONE DAYS .

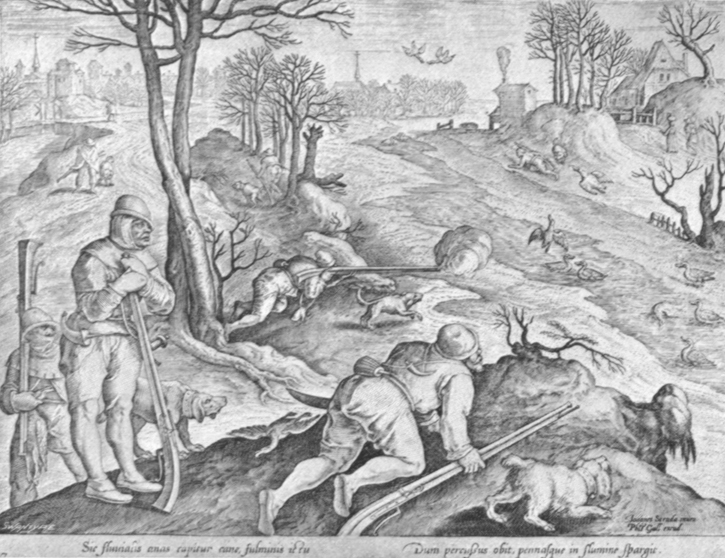

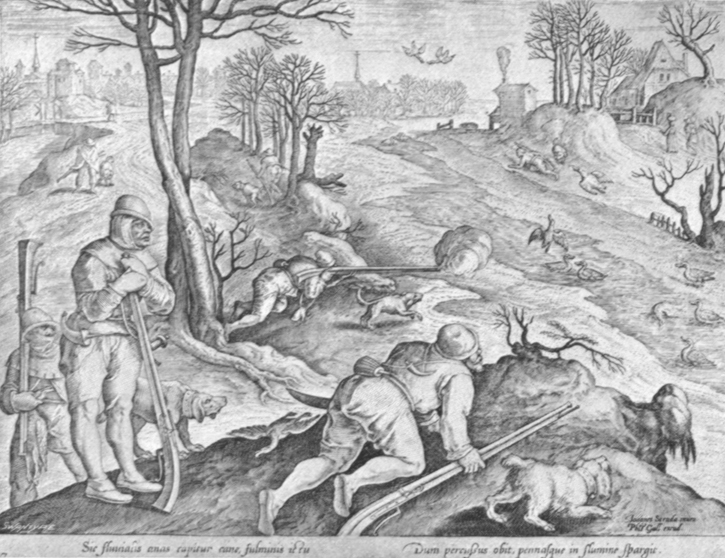

FTER glancing at the quaint engravings, more than three hundred years old, which illustrate these pages, the reader will observe that, notwithstanding many grave defects in drawing and perspective, the old Dutch master Jan van der Straet, otherwise Stradanus, knew how to depict in a lifelike manner sporting scenes whereof many details are of considerable interest to those studying sporting lore. Ph. Galle, the Antwerp engraver, copied a large number of his fellow-countryman’s drawings; one collection particularly, consisting of 104 plates all relating to sport, forms a rare and valuable set. Our reproductions are reduced, but otherwise exact copies of engravings forming part of one of these collections of 104 plates which is in the author’s possession.

FTER glancing at the quaint engravings, more than three hundred years old, which illustrate these pages, the reader will observe that, notwithstanding many grave defects in drawing and perspective, the old Dutch master Jan van der Straet, otherwise Stradanus, knew how to depict in a lifelike manner sporting scenes whereof many details are of considerable interest to those studying sporting lore. Ph. Galle, the Antwerp engraver, copied a large number of his fellow-countryman’s drawings; one collection particularly, consisting of 104 plates all relating to sport, forms a rare and valuable set. Our reproductions are reduced, but otherwise exact copies of engravings forming part of one of these collections of 104 plates which is in the author’s possession.

The first of our illustrations represents a duck-shooting scene on some Netherland stream on a cold winter’s morning; the characteristic figures of the sportsmen being spiritedly drawn, and of interest as throwing light upon the type of sporting arms then in use. Were we not in possession of information which shows that the painter designed this picture between the years 1560 and 1575, one would ascribe to it an earlier date; for the guns depicted in this print have still the matchlock, and the triggers are yet of the old “hooked lever” shape, such as was in use for crossbows throughout the preceding century. Considering that the

510

much more handywheel-lock had been invented half a century previous to the date of our picture, it would show that sportsmen of those days were very slow in adopting the improved means of ignition provided by this important Nürnberg invention. The man who has just let off his unwieldy “fire-tube” at three ducks, apparently not more than gun-length form the muzzle, holds his gun not to his shoulder, but extended over his shoulder, in a decidedly odd-looking manner. The trigger acted as a simple lever upon a catch which released the spring that worked the snake-shaped hammer, in the claws of which the slow-match was fixed. On the outside of the barrel, over the powder-chamber, there was fastened a small tube a couple of inches in length, which acted as rear sight. Through it the aim was taken, the front sight being a coarse bead. Shooting at flying birds or running game was, of course, impossible with such guns; and when we hear of the doughty old Maximilian killing ducks “with great skill,” the feat consisted of pot shots, though probably none were delivered at such close range as is depicted in our Dutch picture. One can understand that miss-fires must have been frequent: indeed, in damp weather they must have been the rule rather than the exception. To obviate as much as possible this defect, sporting guns had sometimes a double lock. An arm of this kind is preserved in the celebrated Ambraser collection in Vienna. It bears the date 1571; its total length is four feet eight inches, the barrel alone measuring forty inches; and the charge could be ignited by either of two hammers, one acting forward, having a flint screwed in the usual place, the other acting backwards in the manner of those in our illustration, carrying the slow match. A close examination of the whole lock shows that the former, as well as the latter, was put on at the start when the gun was built — a circumstance which goes some way in showing that for some time after the invention of the

511

flint-bearing wheel-lock gunmakers were still doubtful concerning its advantages for sporting purposes. It must be mentioned that this interesting old gun has the vertical modern trigger as well as the old-fashioned lever-shaped one which we see in the Stradanus guns. The one acted on the flint hammer, the other set of the matchlock.

No. 2.

Illustration No. 2 shows us a similar scene, with the difference that wild geese instead of ducks are the game the sportsmen seek to bag; though, as we notice from the dead duck slung to the leading Jäger’s belt, the smaller species was not ignored by them. The two powder flasks on the back of the latter remind one of the manifold troubles that beset the path of the gunner in those early days. The larger flask contained the coarse powder with which the piece was charged, while the smaller one was the receptacle for the fine priming powder. The “hail,” as shot was then called, was carried in a leathern pouch, the “measure for measure” proportion of powder to shot being then already known and observed. Upon the breed of the grotesque sporting dog in the foreground one hesitates to express an opinion, though it must be remembered that dogs were much used by wildfowlers, or rather by those practising the art of netting waterfowl. Several old authors have left us accounts of this “sport,” according to which trained dogs were used to swim round the ducks and gradually move them into the narrow channels where trap nets secured the victims. We are also told that small shaggy-coated dogs of reddish colour, resembling the fox, the arch-foe of all wild fowl, were used to attract fowl to that part of the water near which the trapper with his nets was secreted*; the sight of the swimming foxlike dog acting upon the flighting waterfowl

512

much in the same way that the sight of the owl acts upon crows, jays, and other birds, who flock round their dread enemy with a persistency that is taken advantage of to this day.

Netting and snaring were much practised then, for not only was game far more plentiful than now, but the primitive nature of the arms made it impossible to slay it with the ease we can do to-day. Trained decoys, or “traitors” as they were then called, were frequently used, and apparently perfectly authentic instances of a hundred decoy ducks trained to come to a whistle, leading great flocks of their wild brethren to destruction in long tunnel-shaped nets spanning narrow water channels, can be cited from old sporting authors. In our picture (No. 2) we see in the background such a netting arrangement in the act of being closed by two men, who have been watching the gradual approach of their victims from their tent. The two wild geese flying away are probably decoys.

To be a skilful netter and setter of snares, and to be able to use birdcalls, were considered accomplishments worthy of princes and the highest nobles, several French kings and German emperors being devoted to it; while nearly all old sporting authors from Pierre de Crescens in the thirteenth century, and Roy Modus in the following, to Selincourt in the seventeenth century, devote many chapters to it.

Stradanus, who lived for many years in Italy and also died there — he worked for Don John of Austria at Naples — devotes a considerable number of his pictures to this branch of sport, to which the Italian people and also the nobles were for

513

ever much addicted; though, as game birds became less plentiful, the art degenerated into slaughter of small singing birds, until to-day, when for instance the migrating swallows are caught by the hundredweight in nets set in mountain passes frequented by these birds on their passage to warmer climes, it has become a most reprehensible destruction of animal life, to which only a degenerated and unsportsmanlike people could be addicted.

No. 3.

Illustration No. 3 shows us how the “prize of the woods,” the kingly woodcock was netted and snared in days when the art of shooting flying was as yet an undreamt-of accomplishment. Roy Modus already explains to us the several ways of taking this bird: one of them our picture deals with. The well-known mole-catcher’s device of a bent twig, acting as a spring, with a string with a slip-knot attached to it, is a contrivance still much used for woodcock, as the writer saw in Albania. The rets saillantes, or upright flight nets, were of prodigious height and length — so much so that they had to be pulled up and lowered by the means of pulleys. They were set in spots — marshy hollows and clearings — frequented by the becasse during the spring and autumn flight, when, in the dusk of the evening or early dawn, the meshes of the net are more or less invisible to the birds.

No. 4.

Illustration No. 4 is a typical Italian scene of Stradanus’ day, showing us party of men setting out for a nocturnal bird hunt, with bell, flapper or racket, and lantern; the crossbows being probably taken to be used on the way to or from the forest. The latter arm, by the way, was the arbalet à jalet, differing triflingly in shape from the one represented in the next picture, the latter propelling a bullet, while the former discharged a dart or arrow. In the background

514

of our picture we see illustrated the use of the owl, the sight of which attracted the usual promiscuous flock of birds, which are being shot by the sportsmen hidden underneath the boughs of the somewhat elaborate erection beneath.

The lantern or artificial light — la fouée the French called it — was provided with a strong reflector, and was held by a man walking on one side of a hedge, while on the other beaters with long poles disturbed the sleeping birds, who in the first alarm, attracted by the flare of light, fly towards it and are struck down with the racket. Hundreds of thrushes, blackbirds, and other inhabitants of the hedgerow, were thus bagged in a brief space of time.

No. 5.

Pigeons, turtledoves, plovers, fieldfares, and even the lowly lark, were equally the object of the netter, and we are told that as many as a hundred and sixty wild pigeons were got by one fall of the net. Of the latter there were several different kinds; but space lacks us to describe other than the woodcock net and those we shall see employed in taking partridges and the quail in the two following illustrations, Nos. 5 and 6. In the former we see in the foreground the use of the stalking cow, under which guise a man is hidden; the sportsman, armed with a crossbow, approaching the unsuspicious birds under the shelter of the deceptive cow. In the background a nocturnal use of another kind of net is depicted, the strong light of the lantern fascinating the birds startled from their sleep.

No. 6.

In the sixth picture we see employed for quail the “tirasse” net or drag-net, which is, I believe, still occasionally used on the Continent for netting partridges and pheasants for export alive. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it was much used; and at one time the legislature of Toulouse, so Noirmont tells us, had to prohibit it being used for quail. A good pointer was, of course, essential, though

515

probably not the same dog that was used for pointing rabbits — a proceeding which the scene in the background represents. In Louis XIV.’s time “tirassing” pheasants and partridges was sport which the king and his ladies often witnessed; while Ronsard, who was much addicted to it, praises it in rhymes as calling for a clever dog, and on the part of the man the skill of long practice.

Ridinger, the famous delineator of game animals of the last century, has also left us a picture of “tirassing,” and another one illustrating the use of the stalking cow, or, as the French called all such devices, “the partridge horse.” In the latter picture we see that neither of the two men engaged in it, one hidden behind a living horse, the other masked by a sham cow, attempts to shoot the birds, but appear to desire to move them gradually towards a triangular-shaped net ending in a cul-de-sac, the road to destruction being made more tempting by a trail of grain. In his day, we hear, it had ceased to be a sport for which princes cared — a fate which we cannot consider undeserved.

The last two illustrations deal with the more familiar events of the infinitely higher sport of falconry; but in looking at the details we must not forget that in the latter half of the sixteenth century it had long passed the zenith of its glory, when emperors wrote long poems in praise of it, and princes undertook perilous journeys to secure, by foul or fair means, a gerfalcon or goshawk of great fame.

No. 7.

In the first picture we see some nobles, one accompanied by his lady, going to the river-side to fly for the heron, which, in the words of an old writer, was considered “the noblest flight of all others.” Our artist shows us the herons in the several positions most usually observed; for it was an old rule that as the flight

516

at the heron was the most difficult, the hawk once trained to it should not be flown at lesser prey, for this would risk “making a slugge of her.”

No. 8.

The “flight to the field,” as was the technical expression to designate pursuit of partridges and other birds of low flight, as well as of hares, etc., was sport of a lesser degree. This the artist endeavours to indicate in our last illustration; the sportsman being on foot, and of less noble exterior than the seigneur in the preceding picture. The drums and trumpets were used to frighten the ducks from their hiding-places. Spaniels were much used for the flight to the field as well as for the nobler flight; though why all the dogs in Stradanus’s pictures should be of such lusty bulk is more than we are prepared to say, but considering that all the hunting horses seem to be suffering from the same serious defect according to modern notions, speed was probably as little expected from the one as from the other. Sport in Stradanus’s day was still the principal, if not indeed sole occupation of the upper classes, when not engaged in warfare; and as time was of no object to men who had nothing else to which to turn, the racing and record-breaking element of modern sport had not yet commenced to make “the fastest thing out” the sole aim of the good veneur. Man and beast enjoyed themselves leisurely, and waxed fat and sleek.

W. A. BAILLIE-GROHMAN.

* As may be seen to this very day at Fritton Decoy, Norfolk.

<><><><><><><><><><><>

[BACK]

[Blueprint] [NEXT]

FTER glancing at the quaint engravings, more than three hundred years old, which illustrate these pages, the reader will observe that, notwithstanding many grave defects in drawing and perspective, the old Dutch master Jan van der Straet, otherwise Stradanus, knew how to depict in a lifelike manner sporting scenes whereof many details are of considerable interest to those studying sporting lore. Ph. Galle, the Antwerp engraver, copied a large number of his fellow-countryman’s drawings; one collection particularly, consisting of 104 plates all relating to sport, forms a rare and valuable set. Our reproductions are reduced, but otherwise exact copies of engravings forming part of one of these collections of 104 plates which is in the author’s possession.

FTER glancing at the quaint engravings, more than three hundred years old, which illustrate these pages, the reader will observe that, notwithstanding many grave defects in drawing and perspective, the old Dutch master Jan van der Straet, otherwise Stradanus, knew how to depict in a lifelike manner sporting scenes whereof many details are of considerable interest to those studying sporting lore. Ph. Galle, the Antwerp engraver, copied a large number of his fellow-countryman’s drawings; one collection particularly, consisting of 104 plates all relating to sport, forms a rare and valuable set. Our reproductions are reduced, but otherwise exact copies of engravings forming part of one of these collections of 104 plates which is in the author’s possession.