From Manual of Mythology, by Alexander S. Murray; Revised Edition, Philadelphia: David McKay, Publisher, 1895; pp. 84-90.

[84]

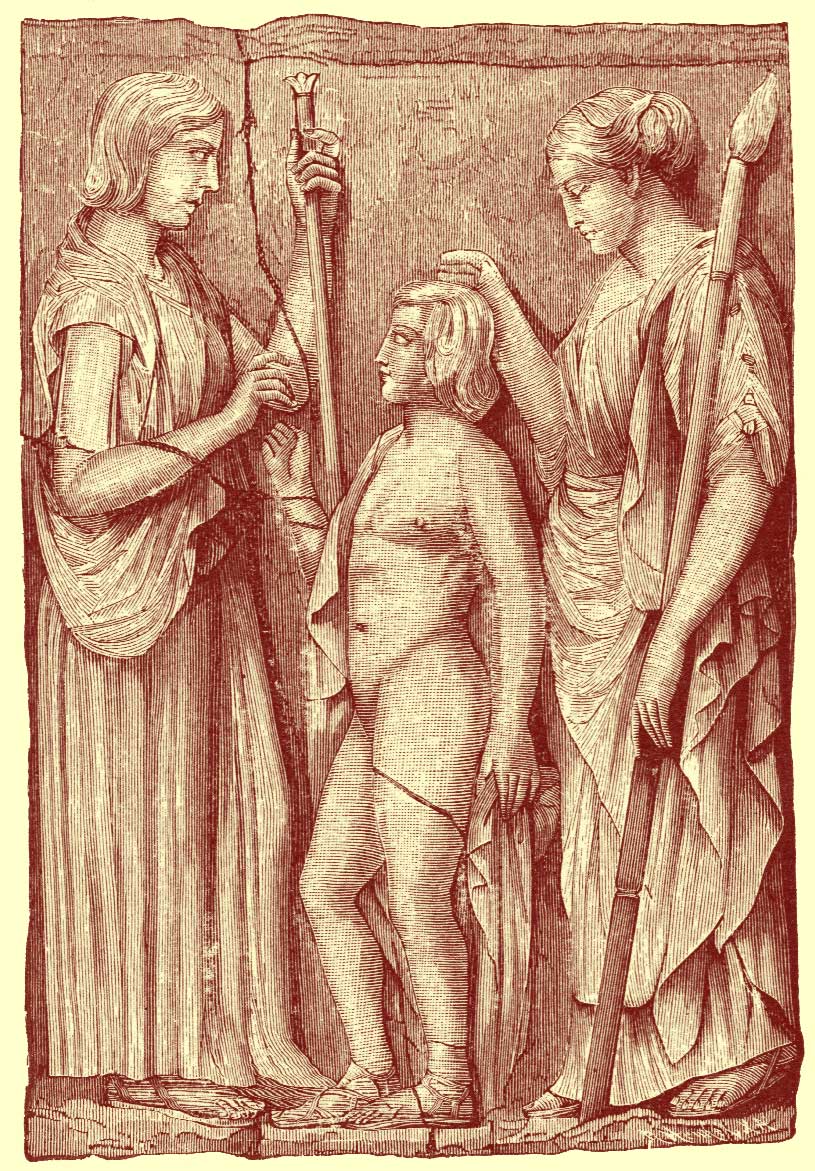

Fig. 11. — Demeter (Vatican, Rome.)

A daughter of Cronus and Rhea, was the goddess of the earth in its capacity of bringing forth countless fruits, the all-nourishing mother, and above all the divine being who watched over the growth of grain, and the various products of vegetation most important to man. The first and grand thought in her worship was the mysterious evolution of life out of the seed which is cast into the ground and suffered to rot — a process of nature which both St. Paul (I. Corinthians xv. 35) and St. John (xii. 24) compare with the attainment of a new life through Christ. The seed left to rot in the ground was in the keeping of her daughter Persephone, the goddess of the lower world, the new life which sprang from it was the gift of Demeter herself; and from this point of view the two goddesses, mother and daughter, were inseparable. They were regarded as ���two in one,��� and styled ���the great deities.���

85From being conceived as the cause of growth in the grain, Demeter next came to be looked on as having first introduced the art of agriculture, and as being the source of the wealth and blessings which attended the diligent practice of that art.

When Hades carried off her beloved young daughter, Demeter, with a mother���s sorrow, lit her torch and, mounting her car drawn by winged snakes, drove through all the lands searching for her, leaving, wherever she rested and was hospitably received, traces of her blessing, in the form of instruction 86 in the art of agriculture. But nowhere in Greece did her blessing descend so richly as in the district of Attica; for there Celēus, of Eleusis, a spot not far from Athens, had received her with most cordial hospitality. In return for this she taught him the use of the plough, and before departing presented to his son, Triptolemus, whom she had nursed, the seed of the barley along with her snake-drawn car, in order that he might traverse all lands, teaching mankind on his way how to sow and to utilize the grain, a task which he performed faithfully, and so extended the art of agriculture to most distant lands.

In Arcadia, Crete, and Samothrace we find her associated with a mythical hero called Jasion, reputed to have been the first sower of grain, to whom she bore a child, whose name of Plutus shows him to be a personification of the wealth derived from the cultivation of grain. In Thessaly there was a legend of her hostility to a hero sometimes called Erysichton, ���the earth-upturner��� or ���the ploughman,��� and sometimes Æthon, a personification of famine. Again, we find a reference to her function as a goddess of agriculture in the story that once, when Poseidon threatened with his superior strength to mishandle her Demeter took the form of a horse and fled from him; but the god, taking the same shape, pursued and overtook her, the result being that she afterwards bore him Arion, a wonderful black horse of incredible speed, and gifted with intelligence and speech like a man. Pain and shame at the birth of such a creature drove her to hide for a long time in a cave, till at last she was purified by a bath in the river Ladon, and again appeared among the other deities. From the necessities of agriculture originated the custom of living in settled communities. It was Demeter who first inspired mankind with an interest in property and the ownership of land, and created the feeling of patriotism and the maintenance of law and order.

87The next phase of her character was that which came into prominence at harvest time, when the bare stubble fields reminded her worshippers of the loss of her daughter Persephone. At that time two kinds of festivals were held in her honor, the one kind called Haloa or Thalysia, being apparently mere harvest festivals, the other called Thesmophoria. Of the latter, as conducted in the village of Halismus in Attica, we know that it was held from the 9th to the 13th of October each year, that it could only be participated in by married women, that at one stage of the proceedings Demeter was hailed as the mother of the beautiful child, and that this joy afterwards gave way to expressions of the deepest grief at her loss of her daughter. At night orgies were held at which mysterious ceremonies were mixed with boisterous amusements of all sorts. The Thesmoi or ���institutions��� from which she derived the title of Thesmophora appear to have referred to married life.

We have no means of knowing to what extent the ancient Greeks based their belief in a happy existence hereafter on the mysterious evolution of life from the seed rotting in the round, which the early Christians adopted as an illustration of the grand change to which they looked forward. But that the myth of the carrying off of Persephone, her gloomy existence under ground, and her cheerful return, originated in the contemplation of this natural process, is clear rfrom the fact that, at Eleusis, Demeter and Persephone always retained the character of seed goddesses, side by side with their more conspicuous character as deities in whose story were reflected the various scenes through which those mortals would have to pass who were initiated into the Mysteries of Eleusis. These mysteries had been instituted by Demeter herself, and we know from the testimony of men like Pindar and Æschylus, who had been initiated, that they were well calculated to awaken most profound feelings of piety and a cheerful hope 88 of better life in the future. It is believed that the ceremony of initiation consisted, not in instruction as to what to believe or how to act to be worthy of Persephone���s favor, but in elaborate and prolonged representations of the various scenes and acts on earth and under it connected with her abduction by Hades. The ceremony took place at night, and it is probable that advantage was taken of the darkness to make the scenes in the lower world more hideous and impressive. Probably these representations were reserved for the Epoptæ, 89 or persons in the final stage of initiation. Those in the earlier stages were called Mystæ. Associated with Demeter and Persephone in the worship of Eleusis was Dionysus in his youthful character and under the name of Jacchus. But at what time this first took place, whether it was due to some local connection with Attica as god of the vine, is not known.

Fig. 11. — Demeter (Vatican, Rome.)

Two festivals of this kind, Eleusinia, were held annually, — the lesser in spring, when the earliest flowers appeared, and the greater in the month of September. The latter occupied nine days, commencing on the night of the 20th with a torch-light procession. Though similar festivals existed in various parts of Greece and even of Italy, those of Eleusis in Attica continued to retain something like national importance, and, from the immense concourse of people who came to take part in them, were among the principal attractions of Athens. The duties of high priest were vested in the family of Eumolpidæ, whose ancestor Eumolpus, according to one account, had been installed in the office by Demeter herself. The festival was brought to a close by games, among which was that of bull-baiting.

In Italy a festival founded on the Eleusinian Mysteries and conducted in the Greek manner was held in honor of Bacchus and Ceres, or Liber and Libera as they were called. It appears, however, to have never commanded the same respect as the original. For we find Romans who had visited Greece, and like Cicero been initiated at Eleusis, returning with a strong desire to see the Eleusinian ceremonies transplanted to Rome. Altogether it is probable that the Roman Ceres was but a weak counterpart of the Greek Demeter.

The attributes of Demeter, like those of Persephone, were ears of corn and poppies; on her head she wore a modius or corn measure as a symbol of the fertility of the earth. Her sacrifices consisted of cows and pigs.

90