Online Introduction to

At the Grass Roots

By Jay Elmer House,

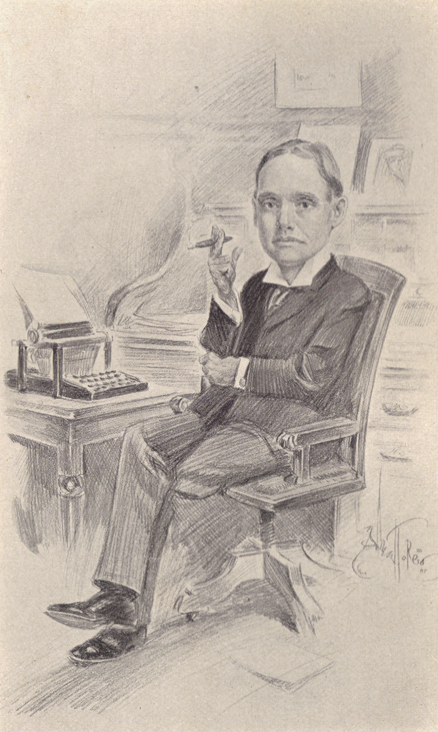

Illustrated by Albert T. Reid

Well, I bought this book for five reasons: It was in the Humor section of the Cincinnati Book Store, it was cheap, it only had one picture (a nice one), it was “monotyped” by a small press in Topeka, Kansas, and it was a small book of few pages.

Now I can tell you that it is not particularly funny. It is, however, a collection of op-ed columns by a journalist, then of the Topeka Capital, called Jay Elmer House, who wrote under the pseudonym of ‘Dodd Gaston.’ He left out any mention of his real first name, Jay, in the authorial notices in the collection. He was born in April 3, 1872, in Plymouth, Illinois, and died in Topeka, Kansas on January 5, 1936.

According to the Archives of Kansas of the Kansas Historical Society, on summarizing their content concerning Jay E. House Papers, he was the author of the Column “On Second Thought,” wrote a play, and was the Mayor of Topeka from 1915 to 1919.

On sifting through these editorials of his, in 1905, House writes of the old days, after the Civil War, when he was growing up on the Kansas prairie as the son of a farming pioneer. The glimpse at the frontier life of a child, and what that child considers worth writing about as an adult is worth reading.

Although this is not a rollicking set of memories overall, he does paint an amusing picture of farm boy antics in The Lure of the Circus. The humor here is subtle even then. But all the emotions elicited as you read the rest of the book are mild: pathos, bitterness, happiness, sorrow and tenderness. Maybe this level was about as much as Kansans could handle in those days when the vagaries of Mother Nature offered so much real and extreme excitement, and had such impact on their lives and professions. Or maybe, in that harsh existence, this was a lot of feeling to them. After all, reading should be restful at the end of the day.

There is, though, a sincere and satisfying nod to a past four-legged friend of his in In Memory of an Ornery Pup. He was clearly heartbroken about the death of a taller pet: read When Flora Died.

The frontispiece of the book, below, a detailed pen and ink sketch by Albert T. Reid, is a full-length portrait of House himself, who died a bachelor, his sister donated some of his papers to a university or library. He was also a bit of a dandy, and certainly a ladies’ man, as you can gather from the pieces. I think he looks a little bit like Peter Lorrie, only skinnier: the eyes and hair, especially:

What a natty dresser! This is clear, even if you are not reminded of Peter L.

While liking women a lot, and either ruled or ruined by the “front-parlor habit,” as he says in When a Man is Worthless, House never mentions any lady in particular. None of his girlfriends form a topic, an innuendo, or even an aside, anywhere in this collection. Elmer liked animals most! And they deserved personal mention, two having their very own chapter, as I said. Since the older I get the more I even like cats, and the less I like people en masse, Elmer’s decision to include those pieces on beloved critters is perfectly alright with me.

As for monotyping, I still don’t know what that is all about.

As to the last of the five reasons mentioned above that this is a short book. It does have enough little period details to be worth the small space of time it will take to read it. So it is fun to find out that a great deal of our ‘modern’ slang and party games are really old, old, old. In these chapters you will see the words “stuck up” and “fad.” Also kissing games, including “Post-Office,” were a big hit in those sober times, despite the feeling that dancing was considered a sin by many!

Then there’s the slang that has not survived the period. For example, “uplift” was a common word, as noun or verb, to describe attempts to improve the intellectual standards of the community and add some culture. This word with the subsquent attempts to put it into practice, is made much of in Queed, written about the same time. It is a good word and worth reviving.

Since it is Christmas, whip out those knitting needles and knit yourself a nubia for any retro-girls of your acquaintance. It was a popular and much-prized accessory in those days. In only one of the more popular online dictionaries is this word defined to fit its context as an item of apparel. At dictionary.reference.com, it states that a nubia is a “a light, knitted woolen head scarf for women.” In 1914, a Woolworth’s pattern book has a crocheted version, which showed the persistence of its popularity.

Almost finally, but importantly, there is enough personality in these pages to draw the conclusion that Jay Elmer House was a decent, tolerant man of the understated sort.

Regarding the text itself. There are very few typos — corrected and noted in the source code — but far too few commas. Why this comma impairment? Beats me. Of course my standards are affected by much reading of comma-rich 19th century writers, and they positively adored those little marks. There are certainly far less commas than other writers of House’s own ’period.’ See Queed, a great novel of the “new South,“ and C. D. Strode’s editorials in Cornfield Philosophy.

On the other hand, maybe commas were just as rare as rain in the prairie. Which calls to mind the only Kansas joke I think I have read, from Masterpieces of Wit and Humor, with Stories and an Introduction by Robert J. Burdette, the World-Renowned Preacher-Humorist, containing all that is Best in the Literature of Laughter of all Nations, copyright by L. G. Stahl, 1903, p. 72:

A TRUE KANSAN

Hans Jensen, a Dane, who appeared before a Kansas judge in order to take out naturalization papers, very easily proved himself worthy of citizen-ship.

“Hans,” said the judge, “are you satisfied with the general conditions of the country? Does this government suit you?”

“Yas, yas,” replied the Dane, “only I would like to see more rain.”

“Swear him!” exclaimed the judge. “I see that he already has the Kansas idea.”

Now this preface is longer than some of the essays in the book! So a last comment, the cover of the book, also designed by Albert T. Reid, is a black engraving on a dark green cloth background. This is unusual, in my experience, and I admired it, so I have included a cropped version of it on every page as a tail-piece. Here it is and you can click on it to go to the rest of the book. BUT!! There are quotes by him and interviews and anecdotes by people who knew Jay Elmer House personally, and/or admired him immensely, down the page.

It is always nice to find a little more detail on people of the early part of the 20th century. Since biographers are mostly interested in people dead for a couple of hundred years, and the writers, teachers and historians of modern times disrespect the lives of their own chroniclers, historians and authors. As a pleasant exception, here is a section of a book by a man who met Jay Elmer House. The is an extract from Interviewing Saints & Sinners, by David W. Hazen, Staff Writer, The Oregonian, Portland, Oregon: Published by Binfords & Mort, 1942:

Although he did not travel all over the world, Jay Elmer House wandered into many nooks and corners of his native land. A farm-reared boy, he early learned to play baseball and to set type. At the turn of the century it was easy for a journeying printer who could really play baseball to get a job. House soon found his way into the city rooms of newspapers, became an excellent reporter.

But he grew homesick often, and would return to Erie, Kansas, “a drowsy county seat town near a sleepy, winding river.” He was several years my senior, but as he talked of his travels, made without benefit of Pullman, I listened eagerly. As we sat under the catalpa trees in the tiny city park, House told of newspaper work in the big cities, of reporting murder cases, of interviewing famous men. During one of these homecomings, he was made foreman of the Erie Sentinel, a weekly printed on an ancient Washington handpress.

About the first thing the new foreman did was to give the job of printer’s devil to the boy who had listened so attentively to the stories of wide adventure. House left The Sentinel several weeks later, and in a few months was baseball reporter and dramatic critic on the Topeka Daily Capital. It wasn’t long until he was columnist on that paper, his cornfed philosophical sayings appearing under the head, “On Second Thought.”

Later he was columnist on the Philadelphia Public Ledger and the New York Evening Post. When he received the final assignment, the one from which no reporter ever returns to write his story, Jay Elmer House was columnist on the Philadelphia Enquirer. I interviewed him a number of times after he became nationally famous. I will always remember those stories of journalistic adventure told in the little city park in the dreamy town of our boyhood.

Another Kansas editor I admired was Edgar Watson Howe, of the Atchison Globe. He was known almost everywhere as Ed Howe. Jay E. House rightfully termed him “the country editor supreme. . . . . ”

I also made a lucky discovery of another biographical sketch, thanks to the fantastic, nay, Herculean work of a modern editor who is interested in his journalistic forefathers, Darrel Miller, Kansas Newspapers Database. He is single-handedly placing online many of the articles from old Kansas newspapers. This article on House is by another friend and fellow-editor, Bert Walker (‘The Village Deacon’), in the Osborne Farmer, March 26, 1908. This was the newspaper for Osborne, Kansas.

My friend Dodd Gaston, by the Village Deacon

For years, I have read untrue, many times weird and oft times silly statements about Dodd Gaston. I have said nothing about them, for such things never worry Gaston. But now I am going to tell about Dodd Gaston, my friend.

To begin with, his name is Jay Elmer House, and he was raised in the little town of Erie, Neosho County, Kansas. I have known him for 14 years. We have worked together, tramped together, slept together, feasted together and gone hungry together. In company have our feet grown sore along the rock-ballasted railroads, and again have we elevated our patent leathers on the upholstered chairs of the club room and sipped Blue Ribbon in plenty and laughed at the days when we had but one shirt apiece.

Gaston is most frequently referred to as “the old crank” of the Topeka Capital. He is neither old nor a crank. He will have to run several years yet before he reaches 40. Gaston and I never quarreled. I guess the reason is because he never tried to tell me any funny stories. I am lazy, but Gaston has me beaten a block. He used to lie in bed and smoke. I would tell him he would burn the house down someday. He would get up, turn on the light and argue to me for an hour that you could set nothing afire from the lighted end of a cigar.

Gaston hasn’t much hair on his head, but it isn’t due to age nor early piety, although when I first became acquainted with him he was singing in a Presbyterian choir just to be near the soprano singer, with whom he was in love. Gaston claims she sang alto, but I know better, for I used to sneak around and go with her some myself.

He is always in love. The ladies who read his stuff and form the idea that he doesn’t like them are sadly mistaken. The reason Gaston has not married is because he never could settle down and love one woman at a time long enough to make a decision.

One day he came into the office wearing a new $40 suit of tailor-made clothes. A little later, the boss came in wearing a new $15 hand-me-down. “Gaston,” said I, “the old man isn’t much of a swell, is he?” “No,” replied Gaston, “but that’s the reason he is our boss.”

I know of but two things that ever worried Gaston to any great extent, outside of the girl question. He could never get a necktie that would tie to suit him, and I never bought a hat that he liked.

Gaston broke into the cut glass set without any trouble. I couldn’t. He always had an engagement that required evening dress. In fact, the demands of society were so heavy on him that he had to shave every day, but at that he is the relentless enemy of the safety razor.

He used to come sailing into our room after attending some big bugvs reception with a ten-cent cigar in his mouth and a carnation in his lapel. “Gaston,” I would say, “I admire your nerve. Here you haven’t got the boxcar knots brushed off your back and you are out in a full dress suit mingling with the millionaires.”

“Well,” he would shoot back, “if you wasn’t a dub and would wear a decent hat you could do it too.”

Gaston dislikes shams and isms and grandstand plays and lambasts them right and left. He is a great theater critic. But it has to be a pretty good show that gets a favorable mention from him. He is always in a fight with the theater-going public of Topeka over the merits of some “star.”

One night Gaston and I dropped in to see a show. The star was one who is well known all over Kansas and has appeared in Osborne a number of times. The company were in awful hard lines. They were hustling hard to get enough money to get out of town and onto the kerosene circuit. They had a lot of good dates in Kansas and a boost from Gaston meant a great deal to them.

As we went back to the office, I said: “Gaston, do you remember when you and I didn’t know where our next meal was coming from? Andrews is in the same fix now. Boost him.”

Gaston went to the office and gave them the finest kind of a sendoff. The article was reproduced all over the kerosene circuit and the show did a big business and was on its feet again in two weeks. I know his heart is tender. He never intentionally hurt anyone in his life.

Gaston ought to be married, because he can get along with anybody. He could always agree with my brother, who is the greatest crank in the world. Anybody who can get along with my brother would be in Paradise with any woman who ever walked.

I have not here told much about Dodd Gaston. He is a fine practical printer and the best all-around newspaper writer in Kansas. But I have tried to show that he is just like other young fellows. He is not cranky, he is not a knocker, he is not a woman hater; he likes baseball and football. He is an even-tempered, genial fellow of good common sense on all topics, and to me a little more agreeable than most any other fellow I ever ran across.

Gaston always boosts in the profession and never knocks. He organized the Handholders’ Union and I stole it from him and brought it out here and palmed it off as original. But he didn’t roar.

I could write a good many columns about Gaston, but he wouldn’t care for any of it except the part that “roasted” him. He likes criticism. He says when people begin to knock on you it is a sign they are sitting up and noticing things.

He has long promised to come out and visit me. If he does, you will always find him at least one of two places. He will either be in the millinery store talking to the girls, or down at the Driving Park practicing baseball with the kids.

Dodd Gaston, my friend, is the commonest sort of a fellow, unadorned with frills or egotism, a loyal chum and the finest companion in the world for the plug country editor.

I found a quote by him that illustrates one of the characterizations above, House once wrote:

“Cheers hearten a man. But jeers are just as essential. They help maintain his sense of balance and proportion.”

Another anecdote comes from The Inland Printer, Volume XLVIII, Chicago: Maclean-Hunter Publishing Corporation, 1912; p. 611:

Jay E. House, the Dodd Gaston of the Topeka Capital, can do any sort of work in a printing-shop, but he quit it because they wouldn’t let him sit around and think.

There is a quote by House, as a space filler, in the Cass City Chronicle, Cass City, Michigan, February 27, 1920:

Jay E. House in the Philadelphia Public Ledger: The smaller the town, the more important an egg with two yolks becomes.

According to a brief notice in the Daily Sentinel, Rome, N.Y., Monday Evening, January 6, 1936; p. 5, House’s column “On Second Thought” was serialized. In the section of the paper called "Deaths Last Night," it states:

Topeka Kans. — Jay E. House, 65, newspaper columnist whose column “On Second Thought” was published in many newspapers in the United States.

I won't pay to read the archive, but the New York Times title of his Obituary is “JAY E. HOUSE DIES; Philadelphia Newspaper Columnist Succumbs During Visit to Kansas.”

Enough research for now! I did find an article in another magazine that I will transcribe later, with another picture of Jay Elmer when he was older.

For now, click on ‘Next’ below, and you can read the book.